Photo: Brian Cooke

interview

Living Legends: How Roxy Music Went From "Inspired Amateurs" To Art Rock Pioneers

Fifty years after their debut, Roxy Music's eight studio albums have been reissued and the band is embarking on a tour. GRAMMY.com spoke with guitarist Phil Manzanera about the band's art rock origins and long tail of influence.

Roxy Music has always been a few steps ahead, and a few degrees to the side, of many of its contemporaries. Helmed by GRAMMY-nominated vocalist/songwriter Bryan Ferry along with Phil Manzanera, Andy Mackay and Paul Thompson (with Brian Eno as an early member), the British group is credited with birthing the art rock movement by infusing glam into rock '70s. This year marks the 50th anniversary of Roxy Music's eponymous debut album.

Inspired by film and fashion, painting and photography, Roxy Music’s output is an aural and visual amalgam that blurs the lines between musical styles. From the group's formation in 1970 to Avalon, its last studio album in 1982, Roxy Music has informed and influenced genres — from experimental prog and glam rock, to new wave and electronic pop — and created an enduring impact.

This year, the group’s eight studio albums — Roxy Music, For Your Pleasure, Stranded, Country Life, Siren, Manifesto, Flesh + Blood and Avalon — have been reissued as special anniversary editions with a new half-speed cut, and revised artwork with lyrics., The Best of Roxy Music was released on vinyl for the first time on Sept. 2. The reissues arrive ahead of Roxy Music’s North American arena tour, which kicks off in Toronto on Sept. 7 at Scotiabank Arena. The last time Roxy Music toured was over a decade ago.

Still, the 2019 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductees have remained active, with and without Roxy Music. This year, Ferry has released a four-track EP of iconic love song covers, Love Letters, and published a book. Mackay, who plays oboe, saxophone and keyboards has released a number of solo albums, written a book on electronic music and studied theology. Drummer Thompson left Roxy Music 1980 and joined an array of other bands, including Concrete Blonde, before returning to Roxy Music in 2011. Guitarist Phil Manzanera produced for Pink Floyd, David Gilmour and John Cale, among others, is currently working on an album with Tim Finn of Crowded House and Split Enz.

From his home in the English countryside, Manzanera spoke with GRAMMY.com about his teenage dream of leaving his exotic world-trotting upbringing for a boarding school in England, where he could connect with fellow musicians. "Through music, you can meet people, you can have fun, you can have an adventure," he says. "I didn't want to learn too quickly. I wanted to spread it out over a whole lifetime. Touch wood, still here."

What was the musical landscape like at the time of Roxy Music’s formation?

In the UK, we were coming out of the period where the big guns, Led Zeppelin and all those bands were to the fore. It was the tail end of the hippie jamming period and the start of prog rock. The drugs had done a lot of those bands in; People were on heroin, so it was very gray and introverted. A bit drab really. The time was ripe for a new bunch to emerge.

By complete happenstance, Bowie and us came to the fore in 1972. On the same day that we released the first Roxy Music album, he released The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. The next week, we were supporting him in a pub in Croydon [South London] called the Greyhound. There was only about 40-50 people there. Every time I used to meet David, we used to have a big banter about it because everyone claims they were there. He was incredibly nice to us. He loved what we were doing. He asked us to be at his support act at the Rainbow Theatre, which is a big deal. He couldn't quite believe that we'd just come out of nowhere, whereas he was [on] his fifth album.

The '70s were such a time of experimentation and new sounds.

We called ourselves inspired amateurs. A bunch of guys who didn't particularly want to be technically brilliant, but wanted to play interesting music. Some of the people in the band have been to art school, so there was this visual side to the whole thing. Music and image are explosive, which we all learn from the Beatles. New fashion designers and photographers were coming up to the age where they were going to be influencers, and they all had a similar aesthetic with the films they liked and visual art and bands that were influential on them. We stuck it all together and presented it in an attractive fashion.

What was the reception for Roxy Music like in the United States at the time?

We went to the U.S. in December '72. We were a bit early. People didn't understand the look of the band. When we got to Fresno, people threw water bombs at us and said, "Get off you faggots." But we were going to continue playing this music regardless of what you throw at us.

It took us a long, long time to have any kind of impact in the States. But what was great and cool was that in San Francisco or L.A. or New York, we attracted the freaks. We were supporting Ten Years After or J. Geils Band, totally not our audience, but all the freaks knew [we] were coming to town and they would be partying at our hotel after the gig.

Roxy Music was very prolific, sometimes putting out two albums a year — originally all written by Bryan Ferry — but you started writing from the third album, Stranded?

The way the band evolved, the first two albums that Eno was involved with were the first period. By the time it came to the third album, Eno had left, and, in no way can you do the same stuff again. There was a desire to do something different. We needed to expand our musical palette, and so me and Andy [Mackay] started contributing music.

The way we write songs in Roxy was so different because we had no idea how to write a song. We did all the music first, which is really dangerous, and then Bryan [Ferry] would try and work out some lyrics. Sometimes it was fabulous. Sometimes it was rubbish. Out of the 80 songs of the Roxy catalog, I would say 70 percent hit the mark and perhaps 30 percent we won't talk about. It's a very different way of working, creating a musical texture and musical world behind this singer with a strange voice, but good looking, so we could get away with it.

You had a whole host of musicians playing on later Roxy Music albums. How was that different for you as far as writing and recording and realizing musical ideas?

There's definitely a difference between the first five years and second five years of Roxy Music. We'd worked with so many other musicians in between, we wanted a bit of that flavor. Bryan, especially, had lived in L.A. for a bit and worked with a lot of American musicians. When we got back together for the second phase of Roxy, which is '77 to '83, by that time, I had my own recording studio and we were using that as our base. Technological innovations affect the way you work in a studio. If you're doing what we're doing, you can use the studio as an instrument. It happened organically because we had the means of production.

But we were coming to New York, and working with Bob Clearmountain at Atlantic Records and at the Power Station, and having these amazing American bass players and drummers, because Paul [Thompson] had left toward the middle of that period. Bob would mix it and he would just get rid of all the s—. He would say, "I'm going to focus on this, and it's going to rock." Thank God for him, otherwise it would have been airy-fairy, and all over the place. He mixed Avalon in one week. Ten tracks, five days, two tracks a day, three hours a track. boom, boom, boom, boom. Done. He just knows what to do. He just had it.

The first half of Roxy Music was hinged on a strong artist/producer relationship with Chris Thomas in the producer’s seat.

We were so lucky to get Chris Thomas. He came on board from the second album. As you know, he assisted George Martin with the Beatles. The whole tradition of recording from Abbey Road was passed on to us via Chris Thomas. Everything I've ever learned to do with production — and I've produced loads of people, was a mixture between what Chris Thomas taught me coming from George Martin and my experiences with Eno. Two totally different approaches.

You seem to get along very well with both Ferry and Eno.

After Eno left, when we were doing Stranded, we were up at Air Studios until 6 o'clock. And then I would go to work on Here Come the Warm Jets with Eno from 6 o’clock onwards. We continued for another three years. We had a band, 801, who played live and all sorts of things. But then he just disappeared.

Your guitar riff from the title track of your solo album K-Scope was sampled on the GRAMMY-winning "No Church in the Wild" by Jay-Z and Kanye West.

That's the only GRAMMY that I've ever been associated with, so cheers Jay-Z and Kanye, and 88-Keys, who was the person responsible for playing it to them.

Did your Rock & Roll Hall of Fame nomination, and induction, come as a surprise?

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame is not on British musicians’ radar too much. I didn’t realize how big a deal it was for us. We hadn't played together for six or seven years. We thought, we’ve got to have rehearsals. We rehearsed for a week because we want to do a good job and acquit ourselves well — especially in front of all those top musicians who are going to be watching us, particularly Fleetwood Mac and Def Leppard, the Zombies and Radiohead.

On the night, at the Brooklyn Center, when I saw 30,000 people, I realized, this is actually a big deal. I’m about to get scared now. We loved it. We had such a great time. When Bryan said, "Shall we do 'In Every Dream,'" which is about an inflatable doll, I thought, I don’t think that’s going to be shown on telly, and it didn’t make it, but it was really great fun to do. I had a great big guitar solo, which wasn’t shown, but I got to show off in front of Brian May and Fleetwood Mac.

How did this 50th anniversary tour come about?

I had done bits and pieces on Bryan’s new solo stuff. We were having a cup of tea at Christmas, and he just said, "Do you fancy doing some gigs?" I said, "Do you want to do them?" And he said, "Yeah." I said, "Well, in that case, I'm always up for the crack."

We don't have management. If we want to do something, we just ring each other up, and say, "You want to do it?" I also thought, these songs don't get an airing by us, the original people, very often. When we come to the U.S., it will have been 20 years. That's not exactly overdoing it. If there's ever a time to do it, it's at 50.

What does the ongoing impact of Roxy Music feel like for you?

I don't think about it at all. We never thought we'd do this tour, but we’re doing it. We're really putting in the hours to make it as good as we possibly can. What I want to see when I look out into the audience is people glammed up. I want to see glam out there: heels and feathers — for men and women.

Photo: pgLang

list

Who Discovered Kendrick Lamar? 9 Questions About The 'GNX' Rapper Answered

Did you know Kendrick Lamar was discovered at just 16 years old? And why did he leave TDE? GRAMMY.com dives deep into some of the most popular questions surrounding the multi-GRAMMY winner.

Editor's note: This article was updated to include the latest information about Kendrick Lamar's 2024 album release 'GNX,' and up-to-date GRAMMY wins and nominations with additional reporting by Nina Frazier.

When the world crowns you the king of a genre as competitive as rap, your presence — and lack thereof — is palpable. After a five-year hiatus, Kendrick Lamar declaratively stomped back on stage with his fifth studio album, Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers, to explain why the crown no longer fits him.

Two years later, Lamar circles back to celebrate the west on 2024's GNX, a 12-track release that revels in the root of his love for hip-hop and California culture, from the lowriders to the rappers that laid claim to the golden state.

“My baby boo, you either heal n—s or you kill n—s/ Both is true, it take some tough skin just to deal with you” Lamar raps on "gloria" featuring SZA, a track that opines on his relationship with the genre.

The Compton-born rapper (who was born Kendrick Lamar Duckworth) wasn't always championed as King Kendrick. In hip-hop, artists have to earn that moniker, and Lamar's enthroning occurred in 2013 when he delivered a now-infamous verse on Big Sean's "Control."

"I'm Makaveli's offspring, I'm the King of New York, King of the Coast; one hand I juggle 'em both," Lamar raps before name-dropping some of the top rappers of the time, from Drake to J.Cole.

Whether you've been a fan of Lamar since before his crown-snatching verse or you find yourself in need of a crash course on the 37-year-old rapper's illustrious career, GRAMMY.com answers nine questions that will paint the picture of Lamar's more than decade-long reign.

Who Discovered Kendrick Lamar?

Due to the breakthrough success of his Aftermath Entertainment debut (good kid, m.A.A.d city), most people attribute Kendrick Lamar's discovery to fellow Compton legend Dr. Dre. But seven years before Dre's label came calling, Anthony "Top Dawg" Tiffith saw potential in a 16-year-old rapper by the name of K.Dot.

Lamar's first mixtape in 2004 was enough for Tiffith's Top Dawg Entertainment (TDE) to offer the aspiring rapper a deal with the label in 2005. However, Lamar would later learn that Tiffith's impact on his life dates back to multiple encounters between his father and the TDE founder, which Lamar raps about in his 2017 track "DUCKWORTH."

How Many Albums Has Kendrick Lamar Released?

Kendrick Lamar has released six studio albums: Section.80 (2011), Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City (2012), To Pimp a Butterfly (2015) DAMN. (2017),Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers (2022), and GNX (2024). Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City, To Pimp a Butterfly and DAMN. received both Rap Album Of The Year and Album Of The Year GRAMMY nominations.

What Is Kendrick Lamar's Most Popular Song?

Across the board, it's "HUMBLE." The 2017 track is Lamar's only solo No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 (he also reached No. 1 status with Taylor Swift on their remix of her 1989 hit "Bad Blood"), and as of press time, "HUMBLE." is also his most-streamed song on Spotify and YouTube.

How Many GRAMMYs Has Kendrick Lamar Won?

As of November 2024, Kendrick Lamar has won 17 GRAMMYs and has received 57 GRAMMY nominations overall, solidifying his place as one of the most nominated artists in GRAMMY history and the second-most nominated rapper of all time, behind Jay-Z. Five of Lamar's 17 GRAMMY wins are tied to DAMN., which also earned Lamar the status of becoming the first rapper ever to win a Pulitzer Prize.

His most recent wins include three awards at the 2023 GRAMMYs, which included two for his album Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers, and Best Rap Performance for "The Hillbillies" with Baby Keem.

Does Kendrick Lamar Have Any Famous Relatives?

He has two: Rapper Baby Keem and former Los Angeles Lakers star Nick Young are both cousins of his.

Lamar appeared on three tracks — "family ties," "range brothers" and "vent" — from Keem's debut album, The Melodic Blue. Keem then returned the favor for Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers, featuring on "Savior (Interlude)" and "Savior" as well as receiving production and writing credits on "N95" and "Die Hard."

Why Did Kendrick Lamar Wear A Crown Of Thorns?

Lamar can be seen sporting a crown of thorns on the Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers album cover. He has sported the look for multiple performances since the project's release.

Dave Free described the striking headgear as, "a godly representation of hood philosophies told from a digestible youthful lens."

Holy symbolism and the blurred line between kings and gods are themes Lamar revisits often on Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers. He uses lines like "Kendrick made you think about it, but he is not your savior" and songs like "Mirror" to reject the unforeseen, God-like expectations that came with his King of Hip-Hop status.

According to Vogue, the Tiffany & Co. designed crown features 8,000 cobblestone micro pave diamonds and took over 1,300 hours of work by four craftsmen to construct.

Why Did Kendrick Lamar Leave TDE?

After five albums, four mixtapes, one compilation project, an EP, and a GRAMMY-nominated Black Panther: The Album, Kendrick Lamar and Top Dawg Entertainment (TDE) confirmed that Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers was the Compton rapper's last project under the iconic West Coast label.

According to Lamar, his departure was about growth as opposed to any internal troubles. "May the Most High continue to use Top Dawg as a vessel for candid creators. As I continue to pursue my life's calling," Lamar wrote on his website in August 2021. "There's beauty in completion."

TDE president Punch expressed a similar sentiment in an interview with Mic. "We watched him grow from a teenager up into an established grown man, a businessman, and one of the greatest artists of all time," he said. "So it's time to move on and try new things and venture out."

Before Lamar's official exit from TDE, he launched a new venture called pgLang — a multi-disciplinary service company for creators, co-founded with longtime collaborator Dave Free — in 2020. The young company has already collaborated with Cash App, Converse and Louis Vuitton.

Has Kendrick Lamar Ever Performed at The Super Bowl?

Yes, Kendrick Lamar performed in the halftime show for Super Bowl LVI in Los Angeles in 2022, alongside fellow rap legends Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg and Eminem, as well as R&B icon Mary J. Blige. Anderson .Paak and 50 Cent also made special appearances during the star-studded performance. As if performing at the Super Bowl in your home city wasn't enough, the Compton rapper also got to watch his home team, the Los Angeles Rams, hoist the Lombardi trophy at the end of the night.

Three years after his first Super Bowl halftime performance, Lamar will return to headline the Super Bowl LIX halftime show on Feb. 9, 2025 — just one week after the 2025 GRAMMYs — at the Caesars Superdome in New Orleans.

Is Kendrick Lamar On Tour?

Yes. Kendrick Lamar is currently scheduled to hit the road with SZA on the Grand National Tour beginning in May 2025. Lamar concluded The Big Steppers Tour in 2022, where he was joined by pgLang artists Baby Keem and Tanna Leone. The tour included a four-show homecoming at L.A.'s Crypto.com Arena in September 2022, followed by performances in Europe,Australia, and New Zealand through late 2022.

Currently, there are no upcoming tour dates scheduled, but fans should check back for updates following the release of GNX.

Latest In Rap Music, News & Videos

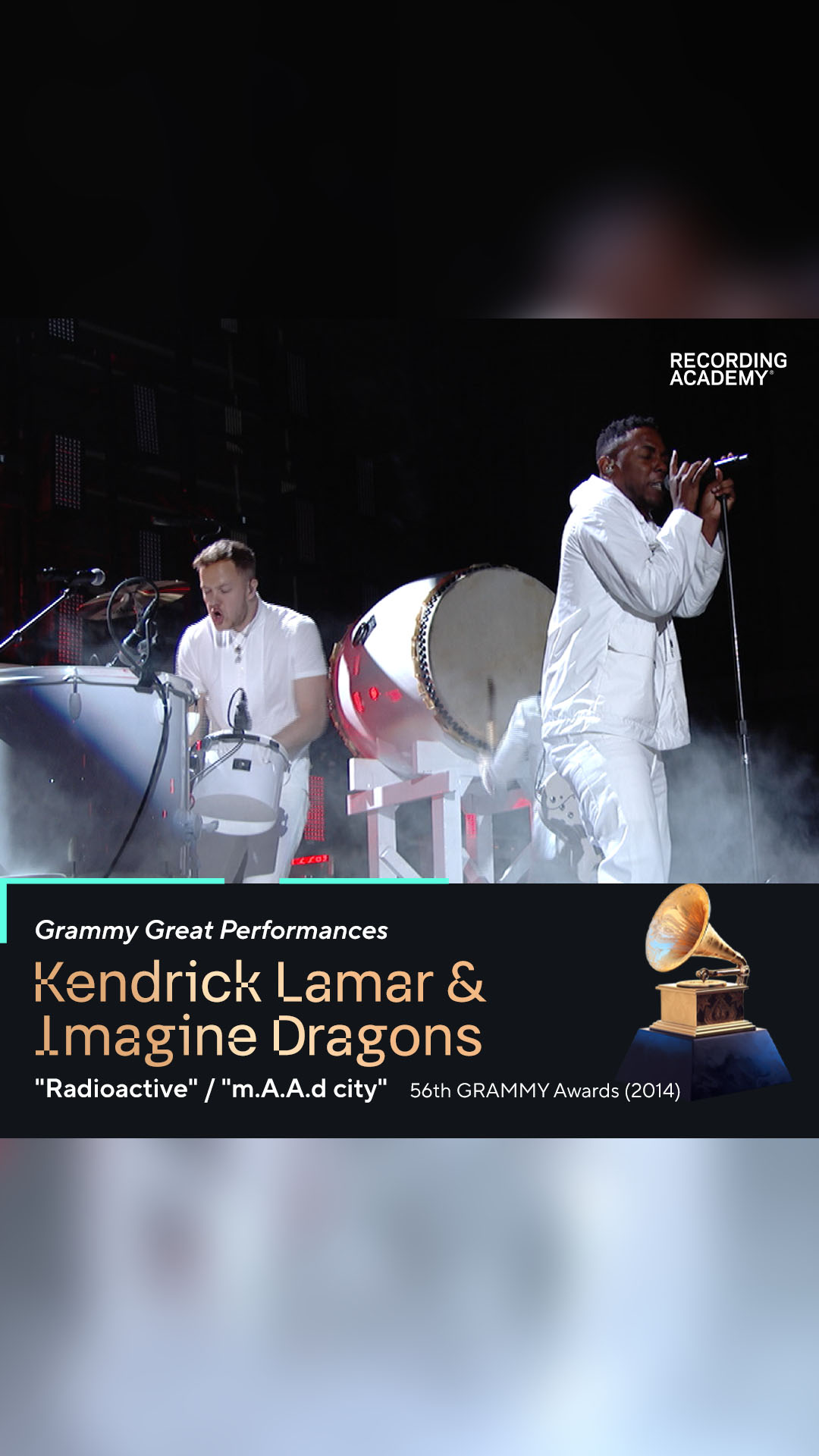

Kendrick Lamar & Imagine Dragons' GRAMMY Mashup

Duckwrth Covers Coldplay's “Clocks” | ReImagined

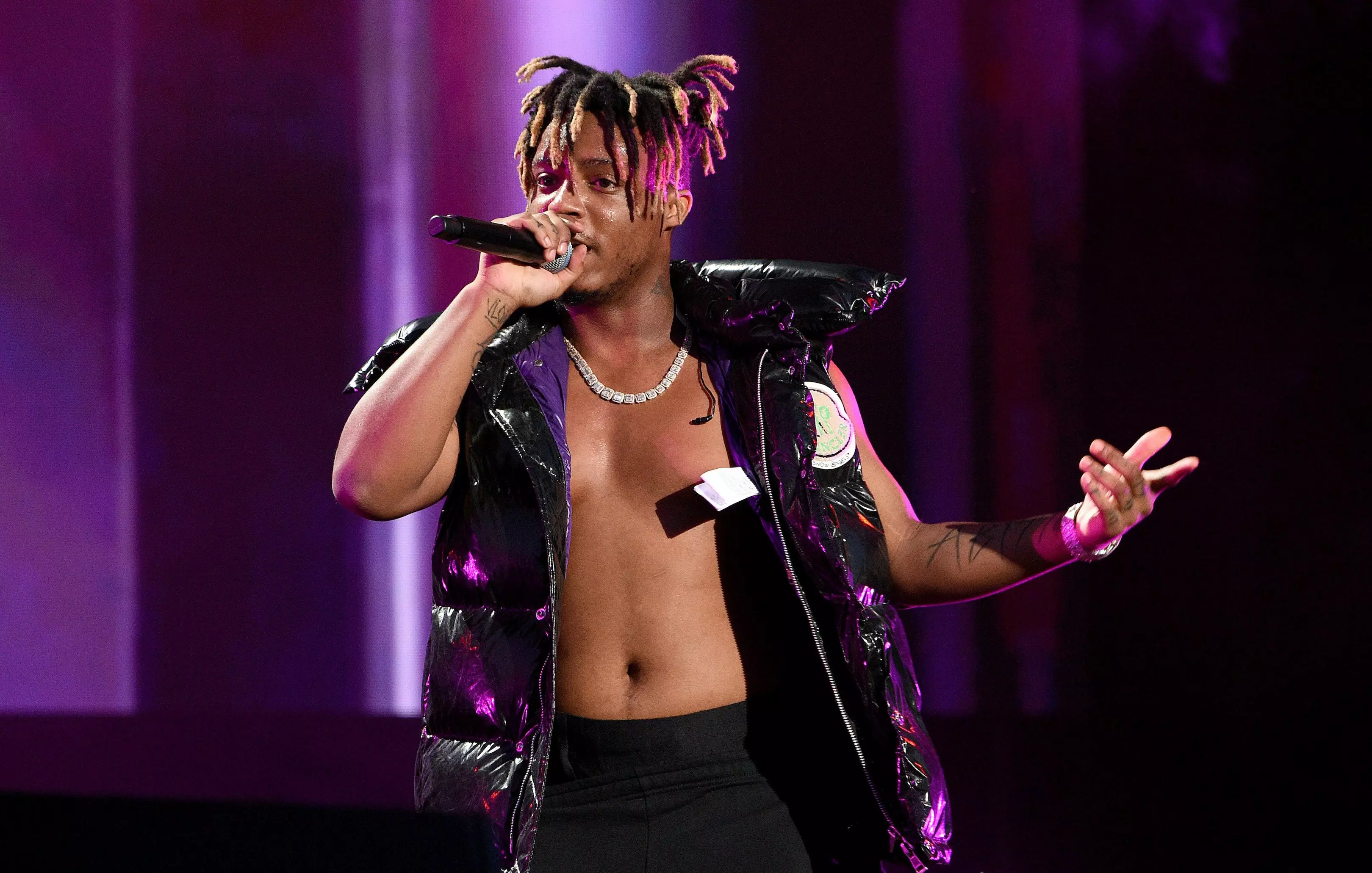

10 Juice WRLD Songs That Showcase The Rapper's Legacy: "Lucid Dreams," "Robbery" & More

10 Facts About MF DOOM's 'Mm.Food': From Special Herbs To OG Cover Art

6 Indian Hip-Hop Artists To Know: Hanumankind, Pho, Chaar Diwaari & More

Photo: Scott Dudelson/Getty Images

interview

Living Legends: Havoc Talks Mobb Deep’s Legacy & The Double-Edged Life Of A Rapper-Producer

GRAMMY.com spoke with Havoc before Mobb Deep drops their final album featuring previously recorded lyrics from the late Prodigy and longtime producer Alchemist on Nov. 2.

Havoc is excited. The Mobb Deep MC and acclaimed industry producer is preparing to film a video with Wu-Tang Clan MC-turned-actor and Internet crush Method Man, and the thought of new music for the masses has him thrilled to pieces.

"This shit is about to be fire," he says enthusiastically. "I can't wait for everybody to check it out."

This single is dropping as part of a larger project with Method Man, which will serve as a tribute to their fallen comrades Ol' Dirty Bastard (ODB) and Prodigy, respectively. But that's not the only new music in the pipeline: after getting the blessing from his late rap partner estate, Havoc will drop the final Mobb Deep album featuring never-before-released verses from the late, great Prodigy, and production by longtime Mobb Deep producer Alchemist, on November 2nd, 2024 — on what would have been Prodigy's 50th birthday.

Born Kejuan Muchita in Brooklyn, New York, Havoc was raised in the Queensbridge Housing Project — the same place that would give the world rappers like MC Shan, Cormega, and of course, Nas — and attended the High School of Art & Design in Manhattan, where he met Albert Johnson (later known as Prodigy). There, the duo would form Poetical Prophets, which later became "The Infamous" Mobb Deep.

Havoc isn't only known for his rhymes — whether as a solo artist, notably on "American Nightmare," where he traded bars with ex-Juice Crew MC Kool G Rap, or as one-half of Mobb Deep. He's also become one of the most acclaimed producers in hip-hop, sitting behind the boards crafting tracks for Lil Wayne, 2 Chainz, and Eminem.

GRAMMY.com spoke with Havoc to talk about his new projects, his legacy with Mobb Deep, and how being both a rapper and a producer is a blessing and a curse.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Let's just dive right into it. Let's talk about your new single with Method Man and your new album.

The concept of the album is to pay tribute to our loved ones who passed away — to Ol' Dirty Bastard, and to Prodigy. We thought it would be cool to do a salute to them. Method Man and I had worked together before this — and seeing that we worked together so well, you know, we decided to do it again.

With the Mobb Deep album: that's been a long time in the making. I wanted to make it years ago, but it wasn't completely my decision. I also needed to work with Prodigy's estate, and they needed time to come to terms with the idea. I gave them as much time as they needed — and of course, we hit a few bumps in the road, but nothing major. We were finally like, "It's time." It's time to continue with the Mobb Deep legacy — to remember Prodigy — and to give the supporters the music that they miss, and love, from Mobb Deep.

Alchemist was one of the people that we worked with when we did the Mobb Deep albums. We were always in contact because we were good friends — and I wanted to have him included to keep up with the Mobb Deep tradition. His inclusion is what our supporters would expect from a classic Mobb Deep album.

I wanted to explore, a little bit, what you said earlier about collaborating with Method Man to both pay tribute to your fallen comrades, and to produce new music. How much of it would you say is paying tribute to ODB and Prodigy, while educating young heads about their history — and how much of it is the "new sound" that's representative of where you two are in your careers right now?

It's equally a bit of both. We're talking about where we're at right now in our careers and our lives — we're both older now. Method Man really doesn't like to curse too much, and I understand — but I'm on there, talking my talk, as usual. Nonetheless, Method Man is in the greatest space he's ever been in, in his life.

You also have a great deal of influence in hip-hop as a producer. Some may go so far as to say that you're one of the most iconic producers of all time. From your perspective, the two-fold question is this: would you say your impact is more felt as a rapper, or as a producer? And is that your legacy, in this industry, and how you'd like to be remembered?

I believe I'm better received as a producer than as a rapper — which is kind of like a gift and a curse. It doesn't bother me too much, but I pour a lot of my heart into writing — I started as a rapper first, and did production later.

I don't know how the transition happened — how I became better known for my production work more than my rapping — but I'd love for people to know how rapping is indeed my passion, because, to me, it's tough being a rapper that writes his lyrics and does his production at the same time. That's a big leap. If you could ask any rapper that same question, they'd tell you that it's a lot to do.

I'm happy that I'm being recognized, but I'd like respect for my pen game.

Let's go back to the early years — 1991, and your appearance in "Unsigned Hype" in The Source when you started to make headway in the mixtape scene in New York. Did you recognize that you were tapping into something special, or did that recognition come later?

I think we knew we tapped into something special, whether people recognized it at the time or not. So, when the recognition from a broader audience came along, it just affirmed what we knew all along.

With "Unsigned Hype," that opened the floodgates for us. One thing led to another, we signed our first record deal, and that's when we started releasing our singles and working with Wu-Tang Clan and other artists. That's when we took hip-hop by storm. So we knew that we'd tapped into something special, and we hadn't even finished the full album yet.

Read more: The Unending Evolution Of The Mixtape: "Without Mixtapes, There Would Be No Hip-Hop"

Where did your mind go with it, once you realized that? Did that change the way you made music, from that point forward?

I believe so. We had a unique recipe, and we followed that recipe for the rest of our career. And we knew that people wanted a specific sound from us, and they wanted us. They didn't want Nas, or Big L, or even Biggie. They wanted Mobb Deep. So we never tried to be like anyone else — we just gave them us, and that was the winning formula.

How did you handle being drawn into the intense East Coast-West Coast feud, particularly after 2Pac named you in 'Hit 'Em Up'?

We were ready for it. We were prepared for war. Look, hip-hop is a contact sport. It is very competitive. So I just looked at it as a rap battle. At the time, I looked at it and thought, "Well, maybe when we see each other in person, there will be a little scuffle." We're artists — we might rap about certain things, and speak about political issues and life in the hood, but at the end of the day, we're entertainers.

I thought people had more respect for human life. I never thought it was a life-and-death game. But when it became a life-and-death game, it shook the core of my existence. I didn't like it at all. And I don't believe that anybody involved — not Pac, not Big, not anybody — deserved to lose their life over some rap beef.

It made me paranoid, and I believe I still have PTSD over it. Biggie Smalls and I share the same birthday. So it hits closer to home for me.

Did you ever get a chance to squash the beef with Pac while he was still alive?

Not at all. He died in the middle of our beef. We put a record out called "Drop a Gem on 'em" in response to "Hit ‘Em Up." We put the single on the radio — it was clear we were dissin' Pac — and, not even seven days after we first dropped the single, we found out he got shot in Vegas. And we pulled the record from the radio — purposefully.

It wasn't until maybe 20 years after the fact that we got a chance to speak with Snoop Dogg. I never thought I'd get a chance to chill around West Coast rappers, but time heals everything. Now, I'm friends with Tha Dogg Pound. I'm friends with Snoop Dogg. I'm in Los Angeles all the time. But that was way down the line.

You have to understand that when it came to Snoop, we didn't have any "beef" to squash, especially after Biggie and Pac were murdered. Once we started hanging out with West Coast artists, we knew that beef was over — and I believe the media hyped it up more than it needed to be, to be honest. No life is worth losing over some rap beef.

For a brief period, you and Prodigy weren't on the best of terms. You even engaged in a bit of a Twitter (now X) back-and-forth that left many fans — myself included — bewildered. Looking back on all of it now, what was the issue at hand, and how did you guys resolve it?

Prodigy and I have known each other for so long, we're brothers. Internally, differences were brewing — but when you're brothers, you're going to get into arguments and disagreements, but at the end of the day, you still love one another, and you're going to work things out.

It was never meant to spill over into the public. And I take responsibility for that. I expressed myself publicly at a time when I shouldn't have been near any electronic devices, you know what I'm saying? I was drinking, and you're emotional when you're drinking — but when I was sober, I realized what I was doing was wrong.

I'm not going to go on record to say what we were beefing about, but at the time, I thought it was valid. Prodigy and I squashed it a year later, though — we knew it was bad for business, plus, we'd known each other for too long to let it go on like this.

Let's touch a little bit on the G-Unit years. There's a lot that you did with the label — and you'd already had that relationship with 50 Cent before the signing. So, tell us what you learned during the G-Unit era about the business, hip-hop, and so on.

I'd begun working on a solo album, and the late Chris Lighty was my manager. He'd told me about this young dude named 50 Cent, and I heard some of his stuff and I was blown away.

I'd told Lighty that I wanted to work with Fif, and 24 hours later, I had him in my studio. At the time, he told me how much he'd admired Mobb Deep, while also hinting that he was considering working with Eminem and Dr. Dre, as they'd shown some interest. He'd even asked me what I thought he should do!

Well, my solo album never came out. Years later, when Mobb Deep got shifted around from label to label, and got dropped from Jive Records, Fif had already sold 10 million records with Get Rich or Die Tryin'. And I didn't believe that he'd even remember me — but when he heard what happened, he called me up and said he wanted to sign Mobb Deep.

Prodigy initially didn't want to do it, but he changed his mind once he sat down with 50 Cent. The rest, as they say, is history. I was so pleased to be down with a crew that had sold so many records. But a lot of our fans, at the time, was hatin' on it. They thought we'd sold out.

I don't even know where to begin with this, but: let's talk about Prodigy's death. It was a gut punch to me, and I can't imagine how it was for you. Where did you find the resolve to take on the responsibility of being the torch-bearer for all things Mobb Deep once Prodigy was gone?

I found it while I was thinking about Prodigy. I was thinking about him, and I was saying, "If God forbid, the shoe was on the other foot, he'd be moving forward." He'd be celebrating the Mobb Deep legacy. I don't think he'd want Mobb Deep to fall to the wayside. He'd be missing me like crazy, but he'd be taking Mobb Deep to the next level.

With that, I found the resolve. I then thought about the supporters, and how they deserved one last Mobb Deep project. And I'm gonna make sure that happens because I don't want to be the one that fumbled the ball just because Prodigy isn't here. I'm the one who has to make sure that the masses hear it.

And this is the last Mobb Deep album. At least, for now. There are still plenty of Mobb Deep verses to go around, but that's not for me to decide. I spoke to the estate about this album, and this album only. That's where my focus is.

So, after this final Mobb Deep hurrah, what is next for Havoc?

There are a lot of things I want to get involved with — documentaries, film scoring, getting my label off the ground, mentoring young artists — that I don't think I'll ever be bored. No, there won't be any Mobb Deep anymore, but there's still Havoc. And that's my legacy.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Khatia Buniatishvili Plays "Mephisto-Waltz No.1"

Peanut Butter Wolf Talks New Campus Christy Album & What's Next For Stones Throw

Warner Music Group's Paul Robinson To Be Honored With 2025 Entertainment Law Initiative Service Award

Your Vote, Your Voice: 6 Reasons Why Your GRAMMY Vote Matters

JOHNNYSWIM Reveal The Mic That Defines Their Sound

Photo: Corine Solberg/Getty Images

interview

Living Legends: Lionel Richie On 'The Greatest Night In Pop,' "American Idol" & The Evolving Essence Of The Music Industry

"When I wrote those lyrics…it was exactly the feeling of where we are now as a world," Lionel Richie says of "We Are the World." In a wide-ranging interview, the four-time GRAMMY winner discusses the iconic charity single and his career to date.

Whether explaining to his parents that the Commodores would be the "Black Beatles" or writing a mega-smash charity single in a single evening, a young Lionel Richie has something of a mantra: "Everything was possible."

When the now-iconic "We Are the World" first hit the airwaves in 1985, listeners surely were awed at the thought of so many legends in one room. Performing under the banner of USA for Africa, the track featured everyone from Ray Charles to Stevie Wonder, Michael Jackson to Bruce Springsteen, Cyndi Lauper to Tina Turner, and sold more than 20 million physical copies to raise money for African famine relief. The song’s recording was documented and encapsulated in the recently released documentary The Greatest Night in Pop.

Richie is the glowing supernova of musicianship creative wrangling at the core of the song and film. "Part of the whole magic of the song was to know the back side of it," Richie tells GRAMMY.com, hinting at the open, warm tone that has characterized his entire career.

Richie's sterling vocals and immaculate songwriting first rose to international prominence in his time as co-lead singer of Motown heroes the Commodores, for whom he wrote songs like "Easy" and "Three Times a Lady." Richie expanded his already endless pop charm as a solo artist, topping charts and winning countless acclaim and listeners’ hearts alike with songs such as "All Night Long (All Night)," "Hello," "Say You, Say Me," and "Dancing on the Ceiling."

When the concept for creating a track to raise funds and awareness for African famine relief was first broached by legendary artist and activist Harry Belafonte and manager Ken Kragen, Richie was tapped to write the song with Michael Jackson. The duo pulled an all-nighter to write the track a day before the first recording session — which also happened to be the very same day Richie was to host the American Music Awards, his first hosting gig on television. (Richie has become a fixture on TV, including his recent stint as a judge on "American Idol.")

Throughout his myriad roles and projects, Lionel Richie remains both incredibly professional and one of the warmest personalities in the music industry — not to mention a captivatingly brilliant musician and four-time GRAMMY winner. GRAMMY.com caught up with Richie to discuss the making of "We Are the World," finding himself in the room with every one of the icons he admired, and the continued need for hope and positivity 40 years later.

I have to tell you, I re-watched The Greatest Night in Pop this morning, and it is no less incredible after another watch.

Thank you. It's one of those moments in time. Just to see the positivity, number one, and number two, the impossibility of how we pull this off. Trying to do that today, you would just want to drive yourself crazy. There's no way today you can keep a secret.

Of course you’d have a leak, and is everybody going to show up? There’d be too many egos. "Leave your ego at the door?" You won't even leave your ego at the phone call.

The whole business has changed. But in the documentary, you really feel the weight of the challenge and the massive scope of opportunity. During that time, were you completely confident or or was there a constant worry that it might fall apart? Perhaps you had so many responsibilities that success and failure didn't even cross your mind.

You know what's so brilliant about being young and naïve? Everything has possibilities.

I look back on my career, when I walked in that door that fateful day that I was going to tell my parents that I was going to drop out of my last semester of my senior year and go full time with the Commodores. And I said, "Mom, Dad, we're the Black Beatles. We're going to take over the world." That takes a lot of just innocence and naivety and youth. Everything was possible. With "We Are the World," we were all kind of sitting there going, "What can we do [to make this work]?" And as we started calling up people, it just became "I'm in." "I'm in." "I'm in."

Of course, Ken [Kragen, manager] didn't tell us that he was making all these phone calls. We just thought it was going to be Quincy [Jones], Stevie [Wonder], Michael [Jackson], and myself. And Harry Belafonte. And the next thing we know, we've got all these artists waiting for the song that we haven't written. [Laughs.]

I think that was so wonderful that you didn't have that level of project in mind. Whilst naivety is part of the process, I feel like if you weren't able to be so in the moment, the song may have come out differently.

I always believe that if you have too much time to think about something, you're going to mess it up. I said yes to something that I didn't realize I had no time to do. This is my solo time in life. I've just left the Commodores; I'm hosting the American Music Awards. I've never done that before.

And of course, the pressure was there as well. Who is this kid to host this show alone? Alone, alone, not with two or three hosts. There was a lot of doubt as to whether this kid could do this or not, you know. As time went on, it just became another part of the story. And I've always believed I'm very good at getting myself into crap. And then I have to work my way out of it.

You're a good swimmer.

[Laughs.] Yeah. And so this thing just started evolving. "Okay, Lionel, what about the rehearsal for the American Music Awards?" And I go, "Oh, that's right. We have to rehearse."

The rehearsal time was also the time we had to cut the track for "We Are the World." And then we have to write the lyrics. Meanwhile, I have to rehearse [for the AMAs]. But, you know, I look back on it, honestly, and it was just divinely guided. Sometimes if you just have a chance to sit back and think about the intricate parts of it, everyone showed up at the right time to do the right thing.

It was astonishing to think about how many roles you had in that record coming to life. You were a writer, a singer, a producer, a coach, a psychiatrist, a guide. And you continue taking on so many different types of projects and roles to this day.

Well, let me tell you what makes things like "We Are the World" happen. I won’t just sit here and talk about, you know, how I did it. That was a room full of pros, you follow me? Quincy Jones, master producer, master arranger. I asked Quincy a very important question one time. I said, "How in the world did you deal with all of those various personalities and stuff?" He said, "What do you think an arranger does?" I said, "What do you mean?" He said, "What do you think I do for a living? My job is to organize chaos." In other words, the woodwinds are playing one thing. The brass are playing something else. The violins are playing something else. And all together it sounds like a song. Well, he was the master of that.

When you bring in artists from all different genres, each one of those artists, A, had their own sound, and B, knew how to deliver it. So all we had to do was kind of set the stage for them to do that half a line and pull it off. But behind the scenes, look at Humberto Gatica. He is a great engineer. How many tracks can you mess up? He had 99 million tracks and all of a sudden we couldn't have a delay [in the schedule]. There was no delay possible. I think what made my part of this whole thing, I was just putting out fires. Wherever there was a fire, like, "Okay, Bob Dylan, you need to go see Stevie Wonder. [Laughs.] And Huey Lewis, you just need to calm down." He thought he was just going to come and hang out.

Oh, Huey is such a fun guy!

Huey was going, "I'm going to sing whose part?" [Laughs.] It made everybody honest. I said, "Okay, Quincy, how are we going to pull this off? Is everybody going to go in the vocal booth one by one to do their parts?" He said, "No, no, no, no. We're going to put them in a circle and let them sing to each other." And I said, "What?"

He said, "I promise you, they'll be perfect on every round." Because when you're facing each other, there is no "Give me another take" or "Give me two more takes" or "Let me warm up." Just the fear factor of facing every artist you've ever admired in your whole life. There's Ray Charles over there. There's Kenny Rogers over here. There’s Diana Ross.

And Tina Turner!

And Bruce. And Billy Joel. We were, basically, the youngsters in the room. There's Michael. We'd all been around in the business a long time, but we'd never just been in a room to face each other.

So I think what was so amazing is when we went around one time at that piano, just to hear how it was all going to sound, that's when we knew we've got something. It was going to be a good sound.

Fitting all those different sounds and voices is such a beautiful achievement. It really makes you stand out, that ability to guide people and projects so naturally. It really makes sense that you have this continued role as a statesman of the industry, even down to your work on "American Idol."

You know what was so great? What we all heard back then, and what still rings true today, there's a word that the world needs right now. It's called hope. [When] that song came out 40 years ago; it was this amazing light, this beacon of hope. People started going, "Ah, okay, you're right. We need to care about each other."

It's one of those aha moments when you realize that a group of us got together and actually made that statement. As world-famous artists, we took all of our light as celebrities and entertainers and songwriters and shined it on hunger and starvation in the world. It was just a great statement.

I’m sure you have countless admirers who come up to you and talk about your work, but can you share some things that listeners have told you about that song in particular?

What I loved is when you start getting the 7- to 12-year-olds [saying] "We sing ‘We Are the World’ in our school!" Then that segues over to "American Idol."

When I first met Bao [Nguyen], the director [of The Greatest Night in Pop], he scared me to absolute death because I'm thinking that we're going to bring in a well-seasoned director from 1983 or 1984. He says, "I was two years old when that song came out in Vietnam." [Laughs.]

A lot of people just heard the song, but they didn't know the background [or my role in it]. So they didn't know that Michael and I wrote the song together. They knew I was maybe in the song, but they didn't know to what degree. I’m having a lot of people just come up to me with the sheer discovery. "Oh, my God, I didn't even know you did it."

"Where have you been?"

It really tells how blessed we were, because think about this now. All of us [working on the song] went on to have careers, major careers; that was the beginning of our big explosion.

What I love the most, I think, is just the fact that what Michael and I set out to do with that song was we wanted not a song, not a hit record. We wanted an anthem. We wanted a song that will stay around generation after generation, year after year. When people ask me right now, "God, Lionel, you need to write another song, because we need it so much today." And I go, "Play the song again."

It's so relevant. Absolutely.

Everything I wanted to say 40 years ago, I would write today. In other words, history just keeps repeating itself over and over again. And everyone keeps thinking you need something new. No, the whole song said everything.

But then when was your last all-nighter? Because that was a pretty epic all-nighter that you had that night.

[Laughs.] That was an "all-two-dayer"! That was the day before rehearsing for the American Music Awards. You then wake up and then actually start rehearsing from 7 in the morning at the Shrine Auditorium 'til the show started, and then to leave there at 11 o'clock at night, 12 o'clock at night. I forgot to also mention [that] I was not quite prepared for hosting, because this was my first time doing it. But also, I wasn't ready to win. [Editor's note: Richie won six times at the AMAs the year, including Favorite Pop/Rock Male Artist.]

It was a lot of moving parts. But the beautiful part about it was, I think the dedication and the hearts of each of those artists. Everybody came to shine their light on this issue. And the brilliance of it is, it worked.

What's something positive that you've been feeling about music lately?

Well, here's what's happening. I went into "American Idol" thinking, There is no possible next level of artistry. Because I've been there, done it, I've seen it. This is my eighth year coming up on "American Idol" and talent keeps showing up. Unique talent keeps showing up. Writers keep showing up. And I think what I'm looking forward to is when the industry can now keep up with the talent. Because we're overflowing with talent.

The problem now is, how do we get all of this talent recognized around the world? I mean, when I get to the top 20 on "American Idol" literally, I could start a record company on the top 20. We're throwing off such amazing talent. You constantly have to think, Okay, what are we doing?

For example, Jennifer Hudson did "American Idol," and she was let go at number nine, and then went on to become a massive star. This year coming up, Carrie Underwood won "American Idol" and here she is now coming back as a judge and mentor.

My situation now is, how do we get more of this talent recognized to the world? We were very fortunate back then because everything back then was global. There were only basically four different networks you could deal with. And then if you want to go outside of that, it's called BBC. What the internet did was great in terms of everybody's on it, but it also made it a big soup. You've got so many different angles and avenues. How do you focus your audience?

I think what's going to happen in the next couple of years is technology is going to be able to help us in a lot of ways. Because there has to be a new model that's going to be able to showcase not only the artists, but then there's the writers, the producers, the engineers, the musicians.

Yes! More focus on the collective who create the art. Where are the credits? I want my liner notes.

Exactly! I don't want to be the guy who’s like, "Bring back the good old days," but…

I think a lot of people are saying the same thing, no matter what age they are.

I couldn't wait to read the liner notes. Who's on that record? Oh my God, that writer was on there. Oh my God, that musician was on there. So-and-so sat in on the session. Part of the whole magic of the song was to know the back side of it, what was really happening. There's a lot that we can discover going forward, but there's a lot that we are losing from the past that I would like to bring up. Because we're not really giving credit where credit is due.

We need time. But we also need the advocate, the voice behind a message, which you are so clearly great at. You saw darkness in the world and put out a song. We know that song is not going to fix whatever the problem is, but the music becomes a comfort. What is that song for you that brings you to the place where you're feeling downright comfort?

I don't want to be the one to go that route, but my go-to for calm is "Easy Like Sunday Morning" ["Easy", from the Commodores’ 1977 self-titled album]. I know that it's always best when you use somebody else's song, but I wrote that song in a state of just that. I wasn't quite sure. I wasn't aware. The other song would be "Zoom" [from the same album]. The lyrics to that song basically sums up exactly where we all are. There's a place we'd all like to go and just hide for a moment to get away from all this craziness. I use those two songs as my mantras just because of the message that it gives.

That duality of "I'm telling you my story, but also we're all sharing this." I love it.

I think the entry of that was, "I may be just a foolish dreamer, but I don't care. All I know is my happiness is out there somewhere." We're all looking for that silver lining, that horizon that we've never seen before. When I wrote those lyrics, I must tell you, it was exactly the feeling of where we are now as a world. Because it was confusing. Think about it. This is the early ‘70s, coming out of the ‘60s, the craziness of Vietnam, and as a kid, what's out there for us? I don't know. What's the possibilities? We're not sure. And so here we are again, yet again faced with this survival of how do we stay sane in this world of insanity?

And how do we feed each other with things that feel nourishing?

What I love about the music business is that what determines a real hit record is when people walk up to you and go, "Lionel, I felt the same way." Now, that means you start realizing that, "Yes, I wrote a love song, but those words helped everybody else. That feeling that I felt is the feeling that everybody else felt."

So it's a confirmation that we're all human. We're all feeling. There are moments of happiness. There are moments of tragedy. And we're all doing this in the same world of trying to cope. And so I always say at the end of the day, there's got to be this common bond of humanity and mankind. There's got to be a thread of hope. Otherwise, we've lost the plot completely.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Khatia Buniatishvili Plays "Mephisto-Waltz No.1"

Peanut Butter Wolf Talks New Campus Christy Album & What's Next For Stones Throw

Warner Music Group's Paul Robinson To Be Honored With 2025 Entertainment Law Initiative Service Award

Your Vote, Your Voice: 6 Reasons Why Your GRAMMY Vote Matters

JOHNNYSWIM Reveal The Mic That Defines Their Sound

Photo: Steve James

interview

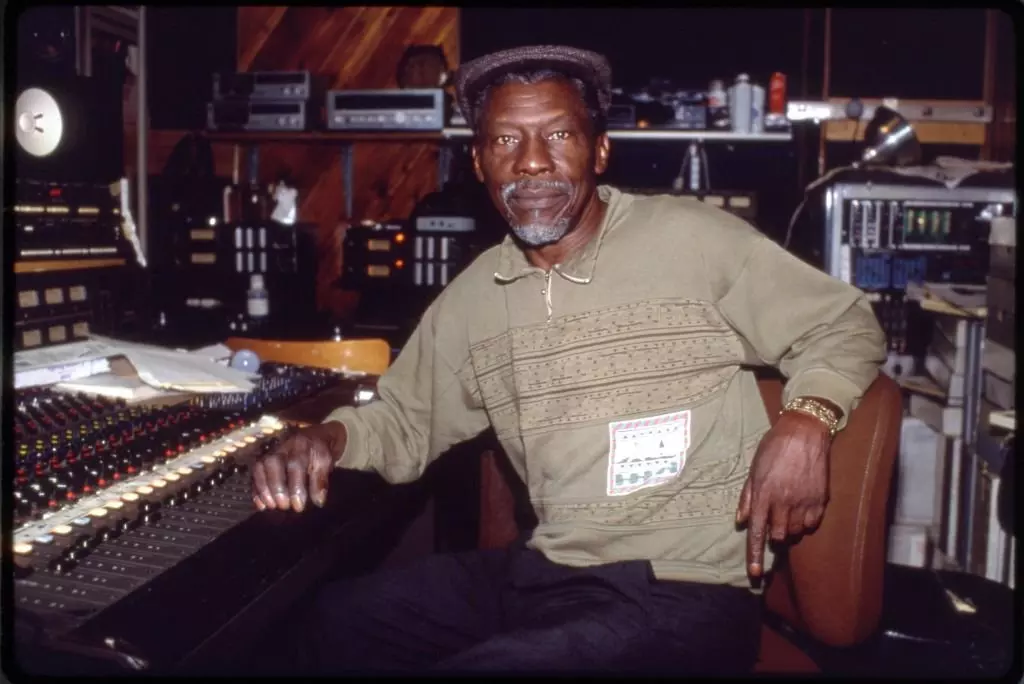

Living Legends: Beres Hammond On His Enduring Career, Timeless Music & 'Brand, Jamaica!'

Beres Hammond has had a lengthy career in reggae, both as a member of Zap Pow and as a solo artist. The two-time GRAMMY nominee discussed his enduring popularity and what he hopes younger artists can learn from his story.

Prior to performing his first song at Reggae Sumfest 2024, Jamaica’s largest music festival, legendary vocalist Beres Hammond shared a concise but important message. "Jamaica," he bellowed, seemingly as a greeting, which he followed by shouting "brand." "We are a brand! I am, you are. Brand! Say it," he instructed. "Brand, Jamaica!"

Throughout his July 20 Sumfest set, Beres interspersed the catchphrase "brand, Jamaica," as if reminding the audience of 15,000 (and the younger artists backstage) at Montego Bay’s Catherine Hall, of Jamaican music’s significant legacy and widespread impact. Countless musical gems comprise brand Jamaica, but few, if any, are more precious than the songs of Beres Hammond.

Born Hugh Beresford Hammond in the small fishing village of Annotto Bay, the two-time GRAMMY nominee first gained notoriety in the early 1970s fronting reggae/R&B fusion outfit Zap Pow. As a solo artist, Beres’ songs primarily explore the erratic complexities of romantic relationships; his charismatic, powerfully granular vocals have been likened to that of soul legends Otis Redding, Teddy Pendergrass and Sam Cooke.

"I never thought I’d reach this point," Hammond tells GRAMMY.com. "Even now, I still show respect to the folks that helped me to grow and are helping me to still be relevant."

At Sumfest, accompanied by his superb Harmony House band and three flawless female backup singers, Beres delved into his beloved catalog, as the audience, spanning three generations of fans, loudly sang along. After performing his first No. 1 single, the 1976 soul nugget "One Step Ahead," which held the top spot in Jamaica for over three months, Beres reminisced onstage, "People thought I was an American guy. It was my first taste of success, but I had no money, I couldn’t even ride the bus. I was broke!"

Beres released a spate of popular singles beginning in the late 1970s into the mid-1980s yet he continued to struggle financially. His situation improved with his initial release on his own Harmony House label, the 1985 hit "Groovy Little Thing."

A sequence of hits followed recorded for various Jamaican producers including 1987’s "What One Dance Can Do," which spawned several answer records (including Hammond's own "She Loves Me Now"). His 1990 defiant social critique, "Putting Up Resistance", produced by Tappa Zukie, remains one of the biggest reggae songs from that era.

Working with producer Donovan Germain’s Penthouse Records, in 1990 Beres laid his vocals over a riddim called "A Love I Can Feel" (after singer John Holt’s 1970 hit, itself a Temptations cover). The resultant "Tempted to Touch" topped reggae charts internationally and commenced a stream of Penthouse hits for Beres that also included "A Little More Time" and "Who Say," collaborations with a gruff-voiced teenaged sensation, Buju Banton.

As his fan base expanded throughout the Caribbean and reggae Diaspora, alongside increasing acclaim for his stellar songwriting and passionate, pliant vocals, it was inevitable Beres would attract major label interest. He signed to Elektra Records, for whom he released just one album, the outstanding In Control, in 1994, featuring the sublime, sultry R&B flavored single "No Disturb Sign."

Between 1996 and 2018 Beres released seven self-produced studio albums through his Harmony House label’s joint venture with Queens, NY based VP Records, including two GRAMMY nominated titles in the Best Reggae Album category. Beres received the nod for his 2001 album, Music is Life at the 44th GRAMMY Awards and again at the 56th GRAMMY Awards for his 2012 album One Love, One Life.

Beres has collaborated with dancehall superstars Sean Paul and Popcaan, and his work has been referenced by Jamaican artists including singer/songwriter Tanya Stephens and sing-jay Mavado. Although he hasn't had a U.S. mainstream hit, Hammond's music is nonetheless recognized by some of the industry’s biggest names. In 2012 Rihanna tweeted the lyrics to Beres’ "They Gonna Talk," obliquely addressing her then rekindled relationship with Chris Brown; at an event in Barbados, she was seen singing along to a medley of Beres hits. Drake conveyed his fondness for the iconic vocalist by retweeting a fan’s declaration that she’d like Beres Hammond to sing at her wedding. Wyclef Jean conclusively expressed the veneration due the bespectacled songster on the outro to his 2001 duet with Hammond "Dance 4 Me," bluntly stating, "All you fake singers, bow down to the legend."

Beres Hammond's most recent single "Let Me Help You" was released on May 3; VP Records says a new Beres project is possibly due by the end of 2024. In between rehearsals for a spate of performances in the New York tri-state area, Beres Hammond sat down with GRAMMY.com and discussed his enduring popularity, his messages to younger artists and the meaning of "brand, Jamaica."

Welcome back to New York City. I was at Reggae Sumfest and I saw your wonderful performance. There’s something extra special about your performances in Jamaica, seeing, hearing different generations of fans singing along to your songs.

What I like most is when the young folks, teens and 20s say, "My mom used to listen to you when she’s in the kitchen working, that’s how I know these songs." They still love them, still sing them. It makes me feel like I came out here to do a job and everything’s been accomplished.

Why do you think your music has such vast appeal among various age groups?

I think it’s the way I present my songs. I make it so easy for everyone to have access. I don’t use Wall Street words; I make it A-B-C. I just do my thing in the simplest manner so everybody can sing it!

You just performed two sold out shows at the Coney Island Amphitheater and the New Jersey Performing Arts Center part of your Forever Giving Thanks tour. So many decades after you started out, that must feel extremely gratifying.

Everyday feels like a new day on the job. I’m giving thanks that I’m in good health and I’ve still got some voice left. All the folks around me, like the band and crew, they’re treating me as if we just started. When you have people around you like that, it’s almost like the journey has just begun.

Have you been working with the same band members for all these years?

For a lifetime, almost. Some have been with me for over 30 years. For the newest members, it might be 10 years.

Throughout your Sumfest performance you intermittently shouted, "brand, Jamaica!" What does that mean?

I was talking about me, what a beautiful brand, but also Jamaica, itself, to the world. Helluva brand! I join the folks that still have Jamaica on the world map as a brand to be reckoned with. Because we nah go nowhere. We deh yah! [We’re here].

I’ve always thought of myself as a brand and upcoming artists should recognize the legacy that’s left here for them. I say "brand" again, to make them understand the role they’re supposed to be playing in what was handed down to them. Be proud of what you’ve got because you are standing on some broad shoulders; be careful how you step on those shoulders.

Coming up in the 1970s and early '80s, whose shoulders did you stand on?

What introduced me to wanting to sing was a few voices including Otis Redding, Sam Cooke, Stevie Wonder, he’s still amazing. I used to love Aretha Franklin and I still love Patti LaBelle. I listened to those voices and said, "Yeah, I would love to sing like them." Then checking on my Jamaican folk, Alton Ellis, Delroy Wilson, hearing those voices, I thought, there must be something out there for me.

Learn more: Remembering Coxsone Dodd: 10 Essential Productions From The Architect Of Jamaican Music

Are there any artists you are mentoring, artists that are standing on your shoulders?

Some of them come up to me and say Father B — they call me all kinda names, Father B, Dada, and they give me some nice accolades. I don’t seek them out, they find me and I always have the right things to say to them, if they ask. Kids still want to learn and being around me, you will learn many things.

Thirty years ago, in 1994, you released your album 'In Control' for Elektra Records. It's still one of my favorite albums.

At that time Elektra went into some merger. The beautiful Elektra crew working with me — some got fired, some went to other places; it was a mess, man. That had a great effect on what the album should have done and really turned me off from Elektra and major labels. This is how people with their big bag of money treat people, come in, push us around. But through the years, I’ve learned that [Elektra] took my music to places that I don’t think I would have reached, so it helped me along.

You continue to have a very successful career, but I can’t help but wonder, had 'In Control' received the push it should have, would your music be better known beyond a reggae audience?

I don’t know, but I know where I stand now and where we are still aiming to go. That never came out of our focus because, hey, the sky’s the limit.

Where are you aiming to go, what are some of the things that you’d still like to do?

I’d like to sing that song that makes the whole world sing along. I’m not sure if I’ve made that one yet.

I hope that my Jamaican brothers and sisters who are making music take it seriously and remember, you’re an influence. Ask yourself, what kind of influence do you want to be to the next generation? Do you want to be the one to make them have a better education? Do you want to be the one that makes them aspire to be leaders? Or do you want to be the one to send them to prison?

Is there any place that you haven’t yet performed but would like to?

People have asked me, what’s my favorite place to perform? I still don’t know. My favorite place is anywhere in the world; once you gather to see me, oh God, that’s my favorite place.

How has the music industry changed in the years that you’ve been in it?

You have to brace to face any new challenge in music. But all I’ve ever wished for is, no matter what kind of changes the music goes through, keep the thing positive so the people can learn. I can’t tell the younger generation what to do. I had my time and did what I had to do; you have to allow them to be themselves, too. Whatever changes the new generation wants to make, I’m there with them; just keep those values and you’re good.

On Jan. 1, 2023, you and Buju Banton put on a very successful concert in Jamaica called Intimate. Any chance you’ll bring that back?

They just talked to me yesterday about it. [Hammond imitates Buju’s resounding voice] "What ‘appen? What are we saying? Second leg? Father B, give I the green light." So, we are looking forward to bringing that back in January 2025.

Read more: Buju Banton's Untold Stories: The Dancehall Legend Shares Tales Behind 10 Of His Biggest Songs

You’ve recorded many songs with Buju and in 2023 you released another collaborative single "We Need Your Love"; an album was expected to follow. Are there any release plans for the Beres/Buju album?

We’ve already recorded 12-15 songs so when them ready, they will tell me. I did songs for Buju and he did songs for me.

Earlier, you mentioned turning on the radio to hear a song that everyone will sing along to; do you listen to Jamaica’s radio stations to hear the latest music?

I listen to talk shows to tap into what the country is doing. You have people calling in, talking about what the prime minister is doing, how many people died today. Music is around me through my kids, my friends. I’m up on everything; without actually listening to it, I’m hearing it.

You have six children; some are pursuing music careers. Tell me about them.

One of them, DJ Inferno, he’s always on the road with me; he plays before I perform, and he mashes up the place all the while. My son Rasheed is in production, trying to establish his own label, he’s ready to start releasing music. One of my daughters, Nastassja, they call her Wizard, she’s a writer, artist, producer. My other daughter, Andrene, is an actress (Andrene Ward-Hammond stars on the CW Network’s "61st Street") and she’s on tour with me looking after my personal needs.

Sometimes I am out here with all six of my children. It’s a beautiful thing. They make me proud.

More Reggae News

How Major Lazer's 'Guns Don't Kill People…Lazers Do' Brought Dancehall To The Global Dance Floor

Living Legends: Beres Hammond On His Enduring Career, Timeless Music & 'Brand, Jamaica!'

Dancehall Legend Spice Reflects On 'Mirror 25,' Her Near-Death Experience & Owning Her Own Vision

10 Artists Shaping Contemporary Reggae: Samory I, Lila Iké, Iotosh & Others

Remembering Coxsone Dodd: 10 Essential Productions From The Architect Of Jamaican Music