Photo: Oscar Sánchez Photography

news

The Unending Evolution Of The Mixtape: "Without Mixtapes, There Would Be No Hip-Hop"

Today, the mixtape holds a variety of meanings — from a curated playlist to a non-label hip-hop release. From the dawn of the cassette to the internet-based culture of mixtape-making, musicians in hip-hop have developed their style via this format.

"Living in the Bronx, we got to hear all the latest music. If a party was on a Friday or a Saturday, by Monday the mixtapes would already be in my neighborhood," Paradise Gray says, beaming.

Now the chief curator and advisor for the soon-to-open Universal Hip Hop Museum in the Bronx — not to mention the co-host of the A&E TV show "Hip-Hop Relics," which follows the quest for genre relics alongside the likes of LL Cool J and Ice T — Gray grew up consuming countless mixtapes from the likes of the L Brothers, Grandmaster Flash, and the Cold Crush Brothers.

"The amount of music and the way it was curated was incredible, and having it on tape was way more valuable than hearing it on the radio because the radio didn’t have a rewind button," he says with a laugh. While the general public may have moved onto other formats, those cassettes are making a comeback and mixtapes continue to pervade every aspect of pop culture — both in their musical impact and nostalgic glory.

Today, the mixtape holds a whole swath of meanings — from a curated playlist to a non-label hip-hop release. But back in the early ‘70s, kids like Gray raised on everything from Motown to Thelonious Monk, George Clinton to James Brown were blending their influences.

"The first tapes were used to record people at places like a park jam, a party, a community gathering," explains Regan Sommer McCoy, founder of the Mixtape Museum, a repository of physical tape collections, nostalgic storytelling, and more. "They were called party tapes then, and people would make copies to give out to friends that couldn’t be there, so they could hear if the DJ was hot or not."

As the form became more popular, DJs like Kid Capri or Brucie B would start recording their club sets as well. "The recordings would sometimes include the DJ shouting out people who were in the room — and if you were in Harlem, maybe there were a few drug dealers in the room who even paid for a shoutout," she adds with a laugh.

McCoy is a longtime devotee of the form and a music industry professional (including a stint as manager of hip-hop legends Clipse). And the more she explored, the more she affirmed that these early tapes are an unparalleled document of a moment in music history.

Gray remembers making his own tapes as a young man in the late ‘70s, discovering the creativity that the new cassette technology could offer.

"We had two recorders, and we would keep the breaks extended even before we were conscious of what we were doing, sampling from cassette to cassette," he says. "We couldn’t afford turntables, but me and my childhood DJ partner, DJ Bob Rock, would make hip-hop practice tapes with the breakbeats and then put them on 8-track. We took over our neighborhood with those tapes because that’s what everybody had in their cars."

Zack Taylor, director of Cassette: A Documentary Mixtape, suggests that the freedom and control Gray felt were a driving force in the ubiquity of mixtapes during hip-hop's early days.

"By all accounts, the music industry in those days was doing everything it could to stifle hip-hop, to hold it back, label it as low-class output," he says. "But the mixtape represented creativity on a personal level. DJ Hollywood, Kool Herc, DJ Clue, these were people who didn’t have the support of a label or an infrastructure, but if they had $100 they could go buy a whole bunch of blank tapes, stay up late on Friday, and have the tapes ready on 125th Street in Harlem on Saturday morning with their blends.

And while some were relishing the individual creativity that cassettes could offer, others were enthused by the ability to listen to music in a more portable way, or merely thrilled by the opportunity to record their favorite songs off the radio. Within this space, talented musicians were finding their footing in a new landscape and developing signature styles.

"There was no such thing as hip-hop at the time — it was really the microcosm of the worldwide Afro-indigenous culture," Gray says. "It’s a sample of everything, not just the breakbeats." Artists were as free to indulge in snippets of Brahms as they were the Delfonics, stringing together their own mixes or making unique blends that would soundtrack an experience that was specific to their own.

Gray also notes that obsessives like the Bronx-based Tape Master would hit up various parties and clubs to document the moment and share the music, in turn allowing this self-defined movement to spread.

A big element of the tapes’ spread was a service called the OJs — a sort of proto-Uber where New Yorkers who owned expensive cars would offer them as a cab service. "If you were going to the club, at least once or twice you would want to show up in the OJ, a Cadillac or an Oldsmobile, and have them playing the hot new hip-hop tapes while they drove you around so everyone could see you and hear you," Gray says.

Listening to those mixtapes as a child, McCoy began to piece together the larger movement, the tapes acting as a sort of encyclopedia with something for everyone. "If I was interested in more R&B blends, I knew that someone like DJ Finesse from Queens would have R&B Blends volume 1 through a million," she explains. "And then I would go to camp every summer, and we would all bring our tapes and mix and swap them. There was a boy from California at camp and I’d get an entirely new sound."

"You couldn't get too hot…because then the RIAA is going to come in"

After first acting as a proving ground for talented DJs, mixtapes became intertwined with lyricists. Many prominent rappers — from Too Short to MC Hammer — started out by selling mixtapes of their work from the trunk of their car, showing up wherever they might find demand. DJs also started recording their sets in professional studios, toeing the line between commercial release and self-distribution — often based on whether there was enough demand to draw the industry’s attention. "You couldn’t get too hot, like DJ Drama, because then the RIAA is going to come in," McCoy says.

Eventually, these DJs would be hired on for entire projects with lyricists or even labels, uniting their voices in their unique blending style. "People like 50 Cent or Diddy would make tapes for their label," McCoy adds. Those artists would hire someone like DJ Whoo Kid to put together an entire tape with the label’s artists featured. "And then the big labels came in, and it got real messy."

Jehnie Burns, author of Mixtape Nostalgia: Culture, Memory, and Representation, argues that this move towards more structured recording processes ties back to the way hip-hop’s origins were separate from the mainstream — both by exclusion and intention.

“Mainstream releases would have to be worried about getting samples approved, making sure it was something that would sell, but hip-hop was often being made by people with something interesting to say that didn’t fit into that mold," Burns says. "It had a lot of similarities to the early days of punk — where local culture was so important, local community, local issues. Mixtapes are able to speak to that community in a way that they understand it and care about."

And when enough of a groundswell happens in a relatively new genre, some artists will work out ways to fit its ethos into the corporate music structure while others will continue to push in the indie world.

McCoy had first hand experience with that thin line while working with Clipse — an experience that proved foundational to the Mixtape Museum. At the time, the duo of Pusha T and No Malice had their contract transferred from Arista to Jive. When their work on Hell Hath No Fury began getting pushback, the duo attempted to get out of their obligation with their new label. "They were going to court with Jive and not able to drop their album, so they were like, ‘F— you, we’ll put out a mixtape,’" McCoy recalls. While label structures might mean trying to force Clipse into a certain box, the freedom of a mixtape meant they would be able to experiment and use their own musical language.

But when someone from the group’s camp dropped 10,000 copies of We Got It 4 Cheap, Vol. 1 (hosted by DJ Clinton Sparks) at McCoy’s Stuyvesant Town apartment, the realities of distributing a mixtape came to bear. Luckily, she had a helping hand in the form of Justo Faison — her then-boyfriend and the founder of the Annual Mixtape Awards. The annual awards honored innovative musicians pushing boundaries in the mixtape form, and Faison had fittingly amassed quite the collection of tapes, vinyl, and other early hip-hop memorabilia.

"I couldn't make a song, but because of the cassette, I could make an album"

After Faison passed in 2005, McCoy and a friend looked around his apartment, wondering what they could do to honor him. "I didn’t know what it meant yet, but I looked around the room and just said ‘Mixtape Museum,’" she remembers. And when she started working in academia, she continued pushing and researching, focused on adding emphasis to the artform that Faison had championed as well.

As the years have passed, countless people have felt that same endless nostalgic draw to the mixtape — as evidenced by the countless memoirs, novels, and films centered on the form. Everyone that made their own mixtape had a unique perspective, a unique purpose, and a yearning to make a document of it, something that would live on longer than a simple playlist.

"Making a mixtape was super empowering," Taylor says. "I couldn’t make a song, but because of the cassette, I could make an album."

Half a century on, the term "mixtape" remains relevant and meaningful. Even kids growing up today, post-8-track, post-cassette, post-CD, post-mp3 know what a mixtape is and the importance it can hold.

"Mixtape has become shorthand for this personal, eclectic collection," Burns says. "There’s a nostalgia factor because Gen X is coming to a certain age, a connection to a slower life less reliant on technology."

In hip-hop specifically, where the term continues to refer to a non-label or non-LP project, it continues to hold the meaning of a testing ground for experimentation and a connection to a niche community.

When Taylor set out in 2011 to make his documentary as an obituary to the mixtape, the Oxford English Dictionary had announced that they’d be removing the word cassette from their printed pages.

"To most people it was dead, but it was starting to have a real revival," he says. "If it were ever going to die, it would’ve happened already. But the portability and personalization will never be replaced." To this day, when shooting commercials, Taylor brings his tape deck (made by new French manufacturer We Are Rewind) and his pleather case of cassettes rather than sticking with a Spotify playlist.

"People are so much more excited to come up and talk about tapes, even from other sets," he says with a laugh. Burns similarly continues to see the advantages mixtapes hold over streaming — especially when it comes to the inability to skip around and the endless ability to rewind and start again. "You’re not skipping tracks or shuffling. You have to listen in the order that someone intentionally put it together," she says.

Perhaps it's that intentionality and experimentation that have allowed the mixtape to constantly evolve and stay relevant. Gray certainly sees it that way.

"Mixtapes are like time machines, musical magic," he says. "And every generation’s youth has the right to make it what they want it to be. Without mixtapes, there would be no hip-hop."

And while some older aficionados may be especially protective of the golden age of hip-hop, Gray sees the mixtape’s place as a living, breathing entity as essential to the genre’s development.

"The mixtape is one of the most invaluable tools that we have available because the internet is a cesspool and needs a filter," he says with a laugh. "Mixtape DJs are filters of culture and vibration. Back in the day, you knew to expect a certain level of quality with a tape from K Slay, Kid Capri, Red Alert, Chuck Chillout, Marley Marl. Today, you know that you’ve got some serious sounds coming out your speakers if it’s that kind of artist curating it."

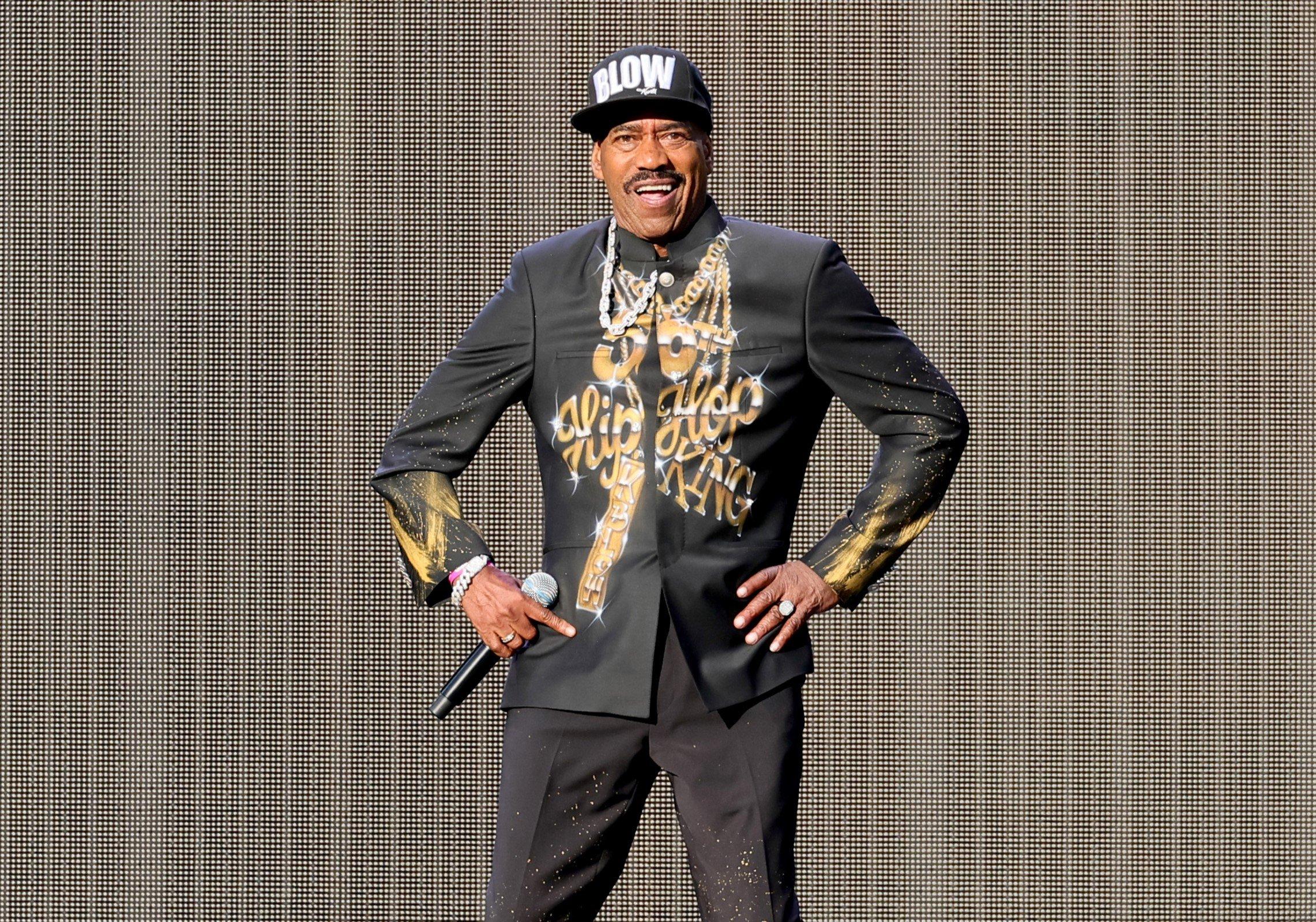

Photo: Theo Wargo/Getty Images

interview

Living Legends: Kurtis Blow On How Hip-Hop Culture Was "Made With Love" & Bringing The Breaks To The Olympics

More than 40 years after he became hip-hop's first commercial breakout star, Kurtis Blow is still moving the culture forward. The rapper and OG B-boy reflects on hip-hop’s rich history, and the impact of seeing hip-hop represented at the 2024 Paris Games.

On the eve of the first-ever Olympic breakdancing competition, hip-hop legend Kurtis Blow was thrilled. It was the first time one of the core elements of hip-hop culture had reached such a global stage.

Alongside DJ Kool Herc (whose breaks provided the soundtrack for B-boys and girls), Blow is credited with popularizing breakdancing. The rapper began breaking as a teenager in the early 1970s, as part of the Hill Boys breaking crew — named for the Sugar Hill area of Harlem where Malcolm X first started his galvanizing pro-Black movement —

And while the International Olympic Committee decided to remove breakdancing from the 2028 Olympics, Blow is unbothered. As far as he’s concerned, his legacy and the legacy of breaking itself is all but set in stone.

"It was definitely something special," Blow tells GRAMMY.com. "And I wasn’t the only one who realized it at the moment it was happening."

Born Kurtis Walker, the Harlem-based Blow began DJing when he was just seven years old. In 1979, the 20-year-old's "Christmas Rappin’" sold over 400,000 copies and turned the up-and-comer into a household name. But it was his follow-up single, 1980’s "The Breaks," that helped launch a whole new genre: rap music. "The Breaks" became the first hip-hop album to receive a gold certification from the RIAA, and proved that Blow wasn’t just a one-trick pony.

Kurtis Blow proved to be immediately influential on the then-nascent rap scene. When Rev. Run of Run-D.M.C. started his career, he billed himself as "The Son of Kurtis Blow" to give him an air of credibility that helped propel the hip-hop trio into the pop culture stratosphere. But Blow's influence didn’t begin and end with his "adopted son": Everyone from Russell Simmons to Wyclef Jean has worked with Blow, and he has been sampled by Nas ("If I Ruled The World" is all but an interpolation of Kurtis Blow’s song of the same name), KRS-One and many others. In fact, more than 100 songs have used samples from "The Breaks," and nearly 1,500 songs have used a sample or an interpolation from Blow’s discography.

Learn more: Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 1970s: Kurtis Blow, Grandmaster Flash, Sugarhill Gang & More

Kurtis Blow was also one of the first rappers to sign to a major label (Mercury Records) and was the first rapper to be a multihyphenate (in addition to his music, Blow worked as an actor on films like In a Dark Place and California Dreamers, and was the musical coordinator for the legendary hip-hop film Krush Groove). Blow continues to work steadily in hip-hop today, though he eschews the legendary breaking parties in favor of cultural events that offer a new glimpse into the culture he helped create.

To wit, Blow is performing with The Hip Hop Nutcracker, in which Tchaikovsky’s classic score is set to breakdancing and modern hip-hop dance; the emcee will perform a brief set to kick off each show. A nationwide tour kicks off in Southern California in November and concludes at the end of December in Durham, North Carolina.

Kurtis Blow spoke with GRAMMY.com about the importance of bringing breaking to the Olympics, reconciling his ministry with modern hip-hop’s message, and his four-decade legacy.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Breakdancing has been a huge part of hip-hop culture for many, many years — and it’s long overdue to be recognized on a global scale like the Olympics. What are your thoughts about seeing this movement that you started getting this kind of recognition?

This whole culture that we call hip-hop started back in the 1960s. With the Civil Rights movement, community organizers, and government officials all debating about something so basic: the right to all be seen as equal and free. It was a traumatic time, you know? But we had music that was so relevant to the whole movement.

By the time the late 1970s and early 1980s came along, everyone was trying to escape all of the traumatic racism that was still going on. And music became our escapism. That’s where breaking came in: everyone was just trying to mimic James Brown on the dance floor. You’d see one guy doing his thing, and everyone would form a circle around him. Pretty soon, someone else would join the circle and challenge him. And before you knew it, there was a whole competition — and whoever won became the most popular in the club.

That kicked it all off. To see it recognized on such a large scale just reaffirms, to me, that this hip-hop culture of ours was made with love.

There were breaking films such as 1985's 'Krush Groove' that were completely revolutionary in that it gave everyone — not just those within the culture — a view into the world of hip-hop, and suggested what it could become. At the time, you were becoming the first commercially successful rapper and one of the pillars of what would become the New York sound. Were you aware that you were on the precipice of something revolutionary?

I don’t want to call myself a visionary or anything like that, but I did know that this was something special, because I saw how quickly it spread around different boroughs in New York City.

From Harlem and the Bronx, and then over into Queens, Brooklyn, and even New Jersey, it was amazing to see everyone just gel around that whole hip-hop scene. As I said before, we all needed that escapism, you know? Forget about your troubles, just come and dance.

With me being in Harlem, right down the block from the Cotton Club and that whole mindset around dancing becoming America’s pastime — just coming from that era, where we had to go to the parties to have a good time — [I knew] that we had created something that would outlast us.

Not only did you attend divinity school, but you are also an ordained minister. How do you bridge those two aspects of your life and how do you reconcile being a rapper with being a minister?

That is such a great question, and thank you for asking.

It’s very simple: God is the Creator. God created hip-hop. We have to start with that, right here. God gave us the talent to perform the music; he gave us the passion to want to spread the music to the masses. He gave us the desire to say, "Hey, come take a look at me! God has blessed me with this — can you do this?"

Now, when you talk about the actual elements of hip-hop — that is, the emcees, and the message that we bring — it’s crucial to understand that we are commanded by God to uplift our community and to show them love. This is the actual essence of hip-hop: peace, unity, love, and just having safe fun.

My mission is to believe in the faith that God is real, and God is in the miracle business. I have seen nothing but miracles for the last 45-50 years in this thing called hip-hop. And it’s important to understand that God is in the mix, and we are all blessed by the common denominator known as hip-hop. It should be our mission to get that back.

As for what’s going on today — the nature of the lyrics, the gangster rap, and all the violence — it didn’t really start out that way, did it? And if we can inspire the future for our youth, then we’ve made a difference. Because the future is in their hands, and we need to inspire them.

But, as a counterpoint, times are different today. And what these men and women are speaking to may not necessarily be destructive — rather, there could be a case made where they’re merely being street poets, and telling the reality of life as they see it. What advice would you give to those people who are telling a different story than the one you told all those years ago?

We are called to be these soldiers, warriors, servants, and communicators. So I understand their reality is different, you know? The world is upside down. The kids out there are just telling it like it is. They’re communicating their reality.

But I think that we should not only communicate how it is, but how it could be. And how it should be.

Think of how different it would be if they also gave some inspiration for a positive future: "Yeah, we goin’ through this, we goin’ through that, but with God, you can overcome all of that. With prayer, you can have miracles, and blessings, come down."

Even if you just understand the nature of the reality that we’re going into right now — things like mass incarceration, the drug epidemic, gun violence, the war profiteering off of Black and brown bodies — it falls upon the shoulders of the elders of this community, this hip-hop movement, to inspire and communicate the possibilities to the younger up-and-comers.

They need to understand that they are the product of royalty. They are the descendants of kings and queens of Africa. They need to honor themselves and honor their ancestors, accordingly.

The culture of hip-hop isn’t just about the music. It’s about fashion, slang, cars, the sports — if you think about it, anthropologically, hip-hop is a civilization onto itself. But, as with all things, so much of it has been co-opted and mainstreamed. How do we bridge the divide between the originators and the colonizers?

Only love can bridge that gap between the ages, the races, our government — the diversity of all these different countries — you know, it needs to be all love.

This is what it’s going to have to take for us to change our present reality. And I feel that in hip-hop, that is the key to that future. The OG’s had the right mindset: peace, love, unity, and having safe fun. We need to get back to that.

When you look back on your career and the legacy you leave behind, how do you want to be remembered?

I remember being in divinity school at Nyack College in New York, and the professor asked the whole class the same thing. And I thought about it for a while, you know? I thought about being remembered as a pioneer of hip-hop — an OG breakdancer — a DJ when I was just seven years old — and an incredible educator.

But what stuck with me was being known as a man of God. That’s it. Because that encompasses everything that I have been through and survived. All of my success, and everything you know about me, comes from God — and to God be the glory.

Latest In Rap Music, News & Videos

Kendrick Lamar & Imagine Dragons' GRAMMY Mashup

Duckwrth Covers Coldplay's “Clocks” | ReImagined

10 Juice WRLD Songs That Showcase The Rapper's Legacy: "Lucid Dreams," "Robbery" & More

10 Facts About MF DOOM's 'Mm.Food': From Special Herbs To OG Cover Art

6 Indian Hip-Hop Artists To Know: Hanumankind, Pho, Chaar Diwaari & More

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

feature

'Run-DMC' At 40: The Debut Album That Paved The Way For Hip-Hop's Future

Forty years ago, Run-DMC released their groundbreaking self-titled album, which would undeniably change the course of hip-hop. Here's how three guys from Queens, New York, defined what it meant to be "old school" with a record that remains influential.

"You don't know that people are going to 40 years later call you up and say, ‘Can you talk about this record from 40 years ago?’"

That was Cory Robbins, former president of Profile Records, reaction to speaking to Grammy.com about one of the first albums his then-fledgling label released. Run-DMC’s self-titled debut made its way into the world four decades ago this week on March 27, 1984 and established the group, in Robbins’ words, "the Beatles of hip-hop."

Rarely in music, or anything else, is there a clear demarcation between old and new. Styles change gradually, and artistic movements usually get contextualized, and often even named, after they’ve already passed from the scene. But Run-DMC the album, and the singles that led up to it, were a definitive breaking point. Rap before it instantly, and eternally, became “old school.” And three guys from Hollis, Queens — Joseph "Run" Simmons, Jason "Jam Master Jay" Mizell, Darryl "D.M.C." McDaniels — helped turn a burgeoning genre on its head.

What exactly was different about Run-DMC? Some of the answers can be glimpsed by a look at the record’s opening song. "Hard Times" is a cover of a Kurtis Blow track from his 1980 debut album. The connection makes sense. Kurtis and Run’s older brother Russell Simmons met in college, and Russell quickly became the rapper’s manager. That led to Run working as Kurtis’ DJ. Larry Smith, who produced Run-DMC, even played on Kurtis’ original version of the song.

But despite those tie-ins, the two takes on "Hard Times" are night and day. Kurtis Blow’s is exactly what rap music was in its earliest recorded form: a full band playing something familiar (in this case, a James Brown-esque groove, bridge and percussion breakdown inclusive.)

What Run-DMC does with it is entirely different. The song is stripped down to its bare essence. There’s a drum machine, a sole repeated keyboard stab, vocals, and… well, that’s about it. No solos, no guitar, no band at all. Run and DMC are trading off lines in an aggressive near-shout. It’s simple and ruthlessly effective, a throwback to the then-fading culture of live park jams. But it was so starkly different from other rap recordings of the time, which were pretty much all in the style of Blow’s record, that it felt new and vital.

"Production-wise, Sugar Hill [the record label that released many key early rap singles] built themselves on the model of Motown, which is to say, they had their own production studios and they had a house band and they recorded on the premises," explains Bill Adler, who handled PR for Run-DMC and other key rap acts at the time.

"They made magnificent records, but that’s not how rap was performed in parks," he continues. "It’s not how it was performed live by the kids who were actually making the music."

Run-DMC’s musical aesthetic was, in some ways, a lucky accident. Larry Smith, the musician who produced the album, had worked with a band previously. In fact, the reason two of the songs on the album bear the subtitle "Krush Groove" is because the drum patterns are taken from his band Orange Krush’s song “Action.”

Read more: Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 1970s: Kurtis Blow, Grandmaster Flash, Sugarhill Gang & More

But by the time sessions for Run-DMC came around, the money had run out and, despite his desire to have the music done by a full band, Smith was forced to go without them and rely on a drum machine.

His artistic partner on the production side was Russell Simmons. Simmons, who has been accused over the past seven years of numerous instances of sexual assault dating back decades, was back in 1983-4 the person providing the creative vision to match Smith’s musical knowledge.

Orange Krush’s drummer Trevor Gale remembered the dynamic like this (as quoted in Geoff Edgers’ Walk This Way: Run-DMC, Aerosmith, and the Song that Changed American Music Forever): “Larry was the guy who said, 'Play four bars, stop on the fifth bar, come back in on the fourth beat of the fifth bar.' Russell was the guy that was there that said, ‘I don’t like how that feels. Make it sound like mashed potato with gravy on it.’”

Explore The Artists Who Changed Hip-Hop

50 Artists Who Changed Rap: Jay-Z, The Notorious B.I.G., Dr. Dre, Nicki Minaj, Kendrick Lamar, Eminem & More

Hip-Hop Just Rang In 50 Years As A Genre. What Will Its Next 50 Years Look Like?

Watch Outkast Humbly Win Album Of The Year For 'Speakerboxxx/The Love Below' In 2004 | GRAMMY Rewind

A Brief History Of Hip-Hop At 50: Rap's Evolution From A Bronx Party To The GRAMMY Stage

GRAMMY Museum To Celebrate 50 Years Of Hip-Hop With 'Hip-Hop America: The Mixtape Exhibit' Opening Oct. 7

Watch Eminem Show Love to Detroit And Rihanna During Best Rap Album Win In 2011 | GRAMMY Rewind

Listen To GRAMMY.com's 50th Anniversary Of Hip-Hop Playlist: 50 Songs That Show The Genre's Evolution

14 New Female Hip-Hop Artists To Know In 2023: Lil Simz, Ice Spice, Babyxsosa & More

6 Artists Expanding The Boundaries Of Hip-Hop In 2023: Lil Yachty, McKinley Dixon, Princess Nokia & More

The 10 Most Controversial Samples In Hip-Hop History

Watch Lauryn Hill Win Best New Artist At The 1999 GRAMMYs | GRAMMY Rewind

19 Concerts And Events Celebrating The 50th Anniversary Of Hip-Hop

Founding Father DJ Kool Herc & First Lady Cindy Campbell Celebrate Hip-Hop’s 50th Anniversary

A Guide To New York Hip-Hop: Unpacking The Sound Of Rap's Birthplace From The Bronx To Staten Island

A Guide To Southern California Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From L.A. & Beyond

10 Crucial Hip-Hop Albums Turning 30 In 2023: 'Enter The Wu-Tang,' 'DoggyStyle,' 'Buhloone Mindstate' & More

The Nicki Minaj Essentials: 15 Singles To Showcase Her Rap And Pop Versatility

11 Hip-Hop Subgenres To Know: From Jersey Club To G-Funk And Drill

5 Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 2020s: Drake, Lil Baby, Ice Spice, 21 Savage & More

A Guide To Southern Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From The Dirty South

A Guide To Bay Area Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From Northern California

A Guide To Texas Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Events

Ludacris Dedicates 2007 Best Rap Album GRAMMY To His Dad | GRAMMY Rewind

Unearthing 'Diamonds': Lil Peep Collaborator ILoveMakonnen Shares The Story Behind Their Long-Awaited Album

10 Bingeworthy Hip-Hop Podcasts: From "Caresha Please" To "Trapital"

Revisiting 'The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill': Why The Multiple GRAMMY-Winning Record Is Still Everything 25 Years Later

10 Must-See Exhibitions And Activations Celebrating The 50th Anniversary Of Hip-Hop

5 Artists Showing The Future Of AAPI Representation In Rap: Audrey Nuna, TiaCorine & More

'Invasion of Privacy' Turns 5: How Cardi B's Bold Debut Album Redefined Millennial Hip-Hop

10 Songs That Show Doja Cat’s Rap Skills: From "Vegas" To "Tia Tamara" & "Rules"

6 Must-Watch Hip-Hop Documentaries: 'Hip-Hop x Siempre,' 'My Mic Sounds Nice' & More...

Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 2010s: Ye, Cardi B, Kendrick Lamar & More

6 Takeaways From Netflix's "Ladies First: A Story Of Women In Hip-Hop"

How Drake & 21 Savage Became Rap's In-Demand Duo: A Timeline Of Their Friendship, Collabs, Lawsuits And More

5 Takeaways From Travis Scott's New Album 'UTOPIA'

Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 2000s: T.I., Lil Wayne, Kid Cudi & More

Songbook: How Jay-Z Created The 'Blueprint' For Rap's Greatest Of All Time

Ladies First: 10 Essential Albums By Female Rappers

How Megan Thee Stallion Turned Viral Fame Into A GRAMMY-Winning Rap Career | Black Sounds Beautiful

How Hip-Hop Took Over The 2023 GRAMMYs, From The Golden Anniversary To 'God Did'

5 Things We Learned At "An Evening With Chuck D" At The GRAMMY Museum

Remembering De La Soul’s David Jolicoeur, a.k.a. Dave and Trugoy the Dove: 5 Essential Tracks

Catching Up With Hank Shocklee: From Architecting The Sound Of Public Enemy To Pop Hits & The Silver Screen

Meet The First-Time GRAMMY Nominee: GloRilla On Bonding with Cardi B, How Faith And Manifestation Helped Her Achieve Success

Hip-Hop's Secret Weapon: Producer Boi-1da On Working With Kendrick, Staying Humble And Doing The Unorthodox

Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 1990s: Snoop Dogg, Digable Planets, Jay-Z & More

10 Albums That Showcase The Deep Connection Between Hip-Hop And Jazz: De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, Kendrick Lamar & More

Hip-Hop Education: How 50 Years Of Music & Culture Impact Curricula Worldwide

Women In Hip-Hop: 7 Trailblazers Whose Behind-The-Scenes Efforts Define The Culture

Watch Flavor Flav Crash Young MC's Speech After "Bust A Move" Wins In 1990 | GRAMMY Rewind

Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 1980s: Slick Rick, RUN-D.M.C., De La Soul & More

Lighters Up! 10 Essential Reggae Hip-Hop Fusions

How Lil Nas X Turned The Industry On Its Head With "Old Town Road" & Beyond | Black Sounds Beautiful

9 Teen Girls Who Built Hip-Hop: Roxanne Shante, J.J. Fadd, Angie Martinez & More

Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 1970s: Kurtis Blow, Grandmaster Flash, Sugarhill Gang & More

Killer Mike Says His New Album, 'Michael,' Is "Like A Prodigal Son Coming Home"

5 Takeaways From 'TLC Forever': Left-Eye's Misunderstood Reputation, Chilli's Motherhood Revelation, T-Boz's Health Struggles & More

It wasn’t just the music that set Run-DMC apart from its predecessors. Their look was also starkly different, and that influenced everything about the group, including the way their audience viewed them.

Most of the first generation of recorded rappers were, Bill Adler remembers, influenced visually by either Michael Jackson or George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic. Run-DMC was different.

"Their fashion sense was very street oriented," Adler explains. "And that was something that emanated from Jam Master Jay. Jason just always had a ton of style. He got a lot of his sartorial style from his older brother, Marvin Thompson. Jay looked up to his older brother and kind of dressed the way that Marvin did, including the Stetson hat.

"When Run and D told Russ, Jason is going to be our deejay, Russell got one look at Jay and said, ‘Okay, from now on, you guys are going to dress like him.’"

Run, DMC, and Jay looked like their audience. That not only set them apart from the costumed likes of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, it also cemented the group’s relationship with their listeners.

"When you saw Run-DMC, you didn’t see celebrity. You saw yourself," DMC said in the group’s recent docuseries.

Read more: 20 Iconic Hip-Hop Style Moments: From Run-D.M.C. To Runways

Another thing that set Run-DMC (the album) and Run-DMC (the group) apart from what came before was the fact that they released a cohesive rap album. Nine songs that all belonged together, not just a collection of already-released singles and some novelties. Rappers had released albums prior to Run-DMC, but that’s exactly what they were: hits and some other stuff — sung love ballads or rock and roll covers, or other experiments rightfully near-forgotten.

"There were a few [rap] albums [at the time], but they were pretty crappy. They were usually just a bunch of singles thrown together," Cory Robbins recalls.

Not this album. It set a template that lasted for years: Some social commentary, some bragging, a song or two to show off the DJ. A balance of records aimed at the radio and at the hard-core fans. You can still see traces of Run-DMC in pretty much every rap album released today.

Listeners and critics reacted. The album got a four-star review in Rolling Stone with “the music…that backs these tracks is surprisingly varied, for all its bare bones” and an A minus from Robert Christgau who claimed “It's easily the canniest and most formally sustained rap album ever.” Just nine months after its release, Run-DMC was certified gold, the first rap LP ever to earn that honor. "Rock Box" also single-handedly invented rap-rock, thanks to Eddie Martinez’s loud guitars.

There is another major way in which the record was revolutionary. The video for "Rock Box" was the first rap video to ever get into regular rotation on MTV and, the first true rap video ever played on the channel at all, period. Run-DMC’s rise to MTV fame represented a significant moment in breaking racial barriers in mainstream music broadcasting.

"There’s no overstating the importance of that video," Adler tells me. vIt broke through the color line at MTV and opened the door to a cataclysmic change."

"Everybody watched MTV forty years ago," Robbins agrees. "It was a phenomenal thing nationwide. Even if we got three or four plays a week of ‘Rock Box’ on MTV, that did move the needle."

All of this: the new musical style, the relatable image, the MTV pathbreaking, and the attendant critical love and huge sales (well over 10 times what their label head was expecting when he commissioned the album from a reluctant Russell Simmons — "I hoping it would sell thirty or forty thousand," Robbins says now): all of it contributed to making Run-DMC what it is: a game-changer.

"It was the first serious rap album," Robbins tells me. And while you could well accuse him of bias — the group making an album at all was his idea in the first place — he’s absolutely right.

Run-DMC changed everything. It split the rap world into old school and new school, and things would never be the same.

Perhaps the record’s only flaw is one that wouldn’t be discovered for years. As we’re about to get off the phone, Robbins tells me about a mistake on the cover, one he didn’t notice until the record was printed and it was too late.

There was something (Robbins doesn’t quite recall what) between Run and DMC in the cover photo. The art director didn’t like it and proceeded to airbrush it out. But he missed something. On the vinyl, if you look between the letters "M" and "C,", you can see DMC’s disembodied left hand, floating ghost-like in mid-air. While it was an oversight, it’s hard not to see this as a sign, a sort of premonition that the album itself would hang over all of hip-hop, with an influence that might be hard to see at first, but that never goes away.

A Guide To New York Hip-Hop: Unpacking The Sound Of Rap's Birthplace From The Bronx To Staten Island

Photo: Matt Winkelmeyer/Getty Images

video

GRAMMY Rewind: Watch Baby Keem Celebrate "Family Ties" During Best Rap Performance Win In 2022

Revisit the moment budding rapper Baby Keem won his first-ever gramophone for Best Rap Performance at the 2022 GRAMMY Awards for his Kendrick Lamar collab "Family Ties."

For Baby Keem and Kendrick Lamar, The Melodic Blue was a family affair. The two cousins collaborated on three tracks from Keem's 2021 debut LP, "Range Brothers," "Vent," and "Family Ties." And in 2022, the latter helped the pair celebrate a GRAMMY victory.

In this episode of GRAMMY Rewind, turn the clock back to the night Baby Keem accepted Best Rap Performance for "Family Ties," marking the first GRAMMY win of his career.

"Wow, nothing could prepare me for this moment," Baby Keem said at the start of his speech.

He began listing praise for his "supporting system," including his family and "the women that raised me and shaped me to become the man I am."

Before heading off the stage, he acknowledged his team, who "helped shape everything we have going on behind the scenes," including Lamar. "Thank you everybody. This is a dream."

Baby Keem received four nominations in total at the 2022 GRAMMYs. He was also up for Best New Artist, Best Rap Song, and Album Of The Year as a featured artist on Kanye West's Donda.

Press play on the video above to watch Baby Keem's complete acceptance speech for Best Rap Performance at the 2022 GRAMMYs, and check back to GRAMMY.com for more new episodes of GRAMMY Rewind.

How The 2024 GRAMMYs Saw The Return Of Music Heroes & Birthed New Icons

Photo: Clarence Davis/NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images

feature

How 1994 Changed The Game For Hip-Hop

With debuts from major artists including Biggie and Outkast, to the apex of boom bap, the dominance of multi-producer albums, and the arrival of the South as an epicenter of hip-hop, 1994 was one of the most important years in the culture's history.

While significant attention was devoted to the celebration of hip-hop in 2023 — an acknowledgement of what is widely acknowledged as its 50th anniversary — another important anniversary in hip-hop is happening this year as well. Specifically, it’s been 30 years since 1994, when a new generation entered the music industry and set the genre on a course that in many ways continues until today.

There are many ways to look at 1994: lists of great albums (here’s a top 50 to get you started); a look back at what fans and tastemakers were actually listening to at the time; the best overlooked obscurities. But the best way to really understand why a single 365 three decades ago had such an impact is to narrow our focus to look at the important debut albums released that year.

An artist’s or group’s debut is their entry into the wider musical conversation, their first full statement about who they are and where in the landscape they see themselves. The debuts released in 1994 — which include the Notorious B.I.G.'s Ready to Die, Nas' Illmatic and Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik from Outkast — were notable not only in their own right, but because of the insight they give us into wider trends in rap.

Read on for some of the ways that 1994's debut records demonstrated what was happening in rap at the time, and showed us the way forward.

Hip-Hop Became More Than Just An East & West Coast Thing

The debut albums that moved rap music in 1994 were geographically varied, which was important for a music scene that was still, from a national perspective, largely tied to the media centers at the coasts. Yes, there were New York artists (Biggie and Nas most notably, as well as O.C., Jeru the Damaja, the Beatnuts, and Keith Murray). The West Coast G-funk domination, which began in late 1992 with Dr. Dre’s The Chronic, continued with Dre’s step brother Warren G.

But the huge number of important debuts from other places around the country in 1994 showed that rap music had developed mature scenes in multiple cities — scenes that fans from around the country were starting to pay significant attention to.

To begin with, there was Houston. The Geto Boys were arguably the first artists from the city to gain national attention (and controversy) several years prior. By 1994, the city’s scene had expanded enough to allow a variety of notable debuts, of wildly different styles, to make their way into the marketplace.

Read more: A Guide To Texas Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Events

The Rap-A-Lot label that first brought the Geto Boys to the world’s attention branched out with Big Mike’s Somethin’ Serious and the Odd Squad’s Fadanuf Fa Erybody!! Both had bluesy, soulful sounds that were quickly becoming the label’s trademark — in no small part due to their main producers, N.O. Joe and Mike Dean. In addition, an entirely separate style centered around the slowed-down mixes of DJ Screw began to expand outside of the South Side with the debut release by Screwed Up Click member E.S.G.

There were also notable debut albums by artists and groups from Cleveland (Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, Creepin on ah Come Up), Oakland (Saafir and Casual), and of course Atlanta — more about that last one later.

1994 Saw The Pinnacle Of Boom-Bap

Popularized by KRS-One’s 1993 album Return of the Boom Bap, the term "boom bap" started as an onomatopoeic way of referring to the sound of a standard rap drum pattern — the "boom" of a kick drum on the downbeat, followed by the "bap" of a snare on the backbeat.

The style that would grow to be associated with that name (though it was not much-used at the time) was at its apex in 1994. A handful of primarily East Coast producers and groups were beginning a new sonic conversation, using innovations like filtered bass lines while competing to see who could flip the now standard sample sources in ever-more creative ways.

Most of the producers at the height of this style — DJ Premier, Buckwild, RZA, Large Professor, Pete Rock and the Beatnuts, to name a few — worked on notable debuts that year. Premier produced all of Jeru the Damaja’s The Sun Rises in the East. Buckwild helmed nearly the entirety of O.C.’s debut Word…Life. RZA was responsible for Method Man’s Tical. The Beatnuts took care of their own full-length Street Level. Easy Mo Bee and Premier both played a part in Biggie’s Ready to Die. And then there was Illmatic, which featured a veritable who’s who of production elites: Premier, L.E.S., Large Professor, Pete Rock, and Q-Tip.

The work the producers did on these records was some of the best of their respective careers. Even now, putting on tracks like O.C.’s "Time’s Up" (Buckwild), Jeru’s "Come Clean" (Premier), Meth’s "Bring the Pain" (RZA), Biggie’s "The What" (Easy Mo Bee), or Nas’ "The World Is Yours" (Pete Rock) will get heads nodding.

Major Releases Balanced Street Sounds & Commercial Appeal

"Rap is not pop/If you call it that, then stop," spit Q-Tip on 1991’s "Check the Rhime." Two years later, De La Soul were adamant that "It might blow up, but it won’t go pop." In 1994, the division between rap and pop — under attack at least since Biz Markie made something for the radio back in the ‘80s — began to collapse entirely thanks to the team of the Notorious B.I.G. and his label head and producer Sean "Puffy" Combs.

Biggie was the hardcore rhymer who wanted to impress his peers while spitting about "Party & Bulls—." Puff was the businessman who wanted his artist to sell millions and be on the radio. The result of their yin-and-yang was Ready to Die, an album that perfectly balanced these ambitions.

This template — hardcore songs like "Machine Gun Funk" for the die-hards, sing-a-longs like "Juicy" for the newly curious — is one that Big’s good friend Jay-Z would employ while climbing to his current iconic status.

Solo Stars Broke Out Of Crews

One major thing that happened in 1994 is that new artists were created not out of whole cloth, but out of existing rap crews. Warren G exploded into stardom with his debut Regulate… G Funk Era. He came out of the Death Row Records axis — he was Dre’s stepbrother, and had been in a group with a pre-fame Snoop Dogg. Across the country, Method Man sprang out of the Wu-Tang collective and within a year had his own hit single with "I’ll Be There For You/You’re All I Need To Get By."

Anyone who listened to the Odd Squad’s album could tell that there was a group member bound for solo success: Devin the Dude. Keith Murray popped out of the Def Squad. Casual came out of the Bay Area’s Hieroglyphics.

Read more: A Guide To Bay Area Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From Northern California

This would be the model for years to come: Create a group of artists and attempt, one by one, to break them out as stars. You could see it in Roc-a-fella, Ruff Ryders, and countless other crews towards the end of the ‘90s and the beginning of the new millennium.

Multi-Producer Albums Began To Dominate

Illmatic was not the first rap album to feature multiple prominent producers. However, it quickly became the most influential. The album’s near-universal critical acclaim — it earned a perfect five-mic score in The Source — meant that its strategy of gathering all of the top production talent together for one album would quickly become the standard.

Within less than a decade, the production credits on major rap albums would begin to look nearly identical: names like the Neptunes, Timbaland, Premier, Kanye West, and the Trackmasters would pop up on album after album. By the time Jay-Z said he’d get you "bling like the Neptunes sound," it became de rigueur to have a Neptunes beat on your album, and to fill out the rest of the tracklist with other big names (and perhaps a few lesser-known ones to save money).

The South Got Something To Say

If there’s one city that can safely be said to be the center of rap music for the past decade or so, it’s Atlanta. While the ATL has had rappers of note since Shy-D and Raheem the Dream, it was a group that debuted in 1994 that really set the stage for the city’s takeover.

Outkast’s Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik was the work of two young, ambitious teenagers, along with the production collective Organized Noize. The group’s first video was directed by none other than Puffy. Biggie fell so in love with the city that he toyed with moving there.

Outkast's debut album won Best New Artist and Best New Rap of the Year at the 1995 Source Awards, though the duo of André 3000 and Big Boi walked on stage to accept their award to a chorus of boos. The disrespect only pushed André to affirm the South's place on the rap map, famously telling the audience, "The South got something to say."

Read more: A Guide To Southern Hip-Hop: Definitive Releases, Artists & Subgenres From The Dirty South

Outkast’s success meant that they kept on making innovative albums for several more years, as did other members of their Dungeon Family crew. This brought energy and attention to the city, as did the success of Jermain Dupri’s So So Def label. Then came the "snap" movement of the 2000s, and of course trap music, which had its roots in aughts-era Atlanta artists like T.I. and producers like Shawty Redd and DJ Toomp.

But in the 2010s a new artist would make Atlanta explode, and he traced his lineage straight back to the Dungeon. Future is the first cousin of Organized Noize member Rico Wade, and was part of the so-called "second generation" of the Dungeon Family back when he went by "Meathead." His world-beating success over the past decade-plus has been a cornerstone in Atlanta’s rise to the top of the rap world. Young Thug, who has cited Future as an influence, has sparked a veritable ecosystem of sound-alikes and proteges, some of whom have themselves gone on to be major artists.

Atlanta’s reign at the top of the rap world, some theorize, may finally be coming to an end, at least in part because of police pressure. But the city has had a decade-plus run as the de facto capital of rap, and that’s thanks in no small part to Outkast.

Why 1998 Was Hip-Hop's Most Mature Year: From The Rise Of The Underground To Artist Masterworks