Photo: Steve James

interview

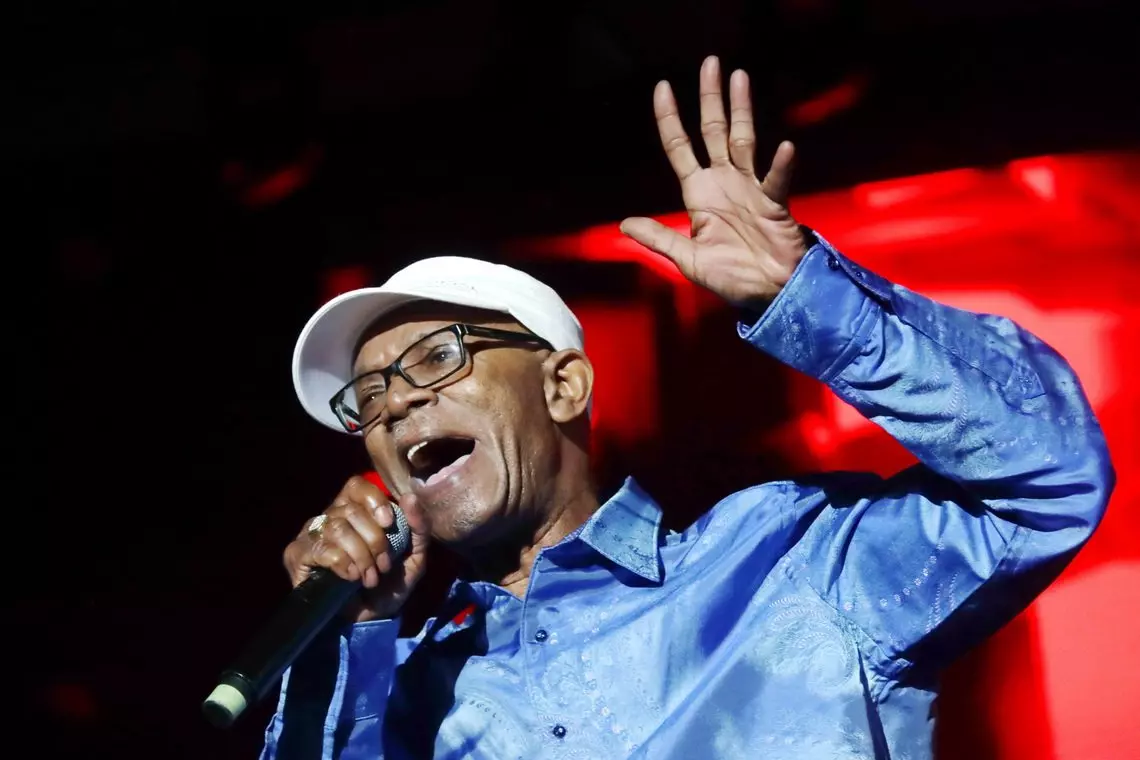

Living Legends: Beres Hammond On His Enduring Career, Timeless Music & 'Brand, Jamaica!'

Beres Hammond has had a lengthy career in reggae, both as a member of Zap Pow and as a solo artist. The two-time GRAMMY nominee discussed his enduring popularity and what he hopes younger artists can learn from his story.

Prior to performing his first song at Reggae Sumfest 2024, Jamaica’s largest music festival, legendary vocalist Beres Hammond shared a concise but important message. "Jamaica," he bellowed, seemingly as a greeting, which he followed by shouting "brand." "We are a brand! I am, you are. Brand! Say it," he instructed. "Brand, Jamaica!"

Throughout his July 20 Sumfest set, Beres interspersed the catchphrase "brand, Jamaica," as if reminding the audience of 15,000 (and the younger artists backstage) at Montego Bay’s Catherine Hall, of Jamaican music’s significant legacy and widespread impact. Countless musical gems comprise brand Jamaica, but few, if any, are more precious than the songs of Beres Hammond.

Born Hugh Beresford Hammond in the small fishing village of Annotto Bay, the two-time GRAMMY nominee first gained notoriety in the early 1970s fronting reggae/R&B fusion outfit Zap Pow. As a solo artist, Beres’ songs primarily explore the erratic complexities of romantic relationships; his charismatic, powerfully granular vocals have been likened to that of soul legends Otis Redding, Teddy Pendergrass and Sam Cooke.

"I never thought I’d reach this point," Hammond tells GRAMMY.com. "Even now, I still show respect to the folks that helped me to grow and are helping me to still be relevant."

At Sumfest, accompanied by his superb Harmony House band and three flawless female backup singers, Beres delved into his beloved catalog, as the audience, spanning three generations of fans, loudly sang along. After performing his first No. 1 single, the 1976 soul nugget "One Step Ahead," which held the top spot in Jamaica for over three months, Beres reminisced onstage, "People thought I was an American guy. It was my first taste of success, but I had no money, I couldn’t even ride the bus. I was broke!"

Beres released a spate of popular singles beginning in the late 1970s into the mid-1980s yet he continued to struggle financially. His situation improved with his initial release on his own Harmony House label, the 1985 hit "Groovy Little Thing."

A sequence of hits followed recorded for various Jamaican producers including 1987’s "What One Dance Can Do," which spawned several answer records (including Hammond's own "She Loves Me Now"). His 1990 defiant social critique, "Putting Up Resistance", produced by Tappa Zukie, remains one of the biggest reggae songs from that era.

Working with producer Donovan Germain’s Penthouse Records, in 1990 Beres laid his vocals over a riddim called "A Love I Can Feel" (after singer John Holt’s 1970 hit, itself a Temptations cover). The resultant "Tempted to Touch" topped reggae charts internationally and commenced a stream of Penthouse hits for Beres that also included "A Little More Time" and "Who Say," collaborations with a gruff-voiced teenaged sensation, Buju Banton.

As his fan base expanded throughout the Caribbean and reggae Diaspora, alongside increasing acclaim for his stellar songwriting and passionate, pliant vocals, it was inevitable Beres would attract major label interest. He signed to Elektra Records, for whom he released just one album, the outstanding In Control, in 1994, featuring the sublime, sultry R&B flavored single "No Disturb Sign."

Between 1996 and 2018 Beres released seven self-produced studio albums through his Harmony House label’s joint venture with Queens, NY based VP Records, including two GRAMMY nominated titles in the Best Reggae Album category. Beres received the nod for his 2001 album, Music is Life at the 44th GRAMMY Awards and again at the 56th GRAMMY Awards for his 2012 album One Love, One Life.

Beres has collaborated with dancehall superstars Sean Paul and Popcaan, and his work has been referenced by Jamaican artists including singer/songwriter Tanya Stephens and sing-jay Mavado. Although he hasn't had a U.S. mainstream hit, Hammond's music is nonetheless recognized by some of the industry’s biggest names. In 2012 Rihanna tweeted the lyrics to Beres’ "They Gonna Talk," obliquely addressing her then rekindled relationship with Chris Brown; at an event in Barbados, she was seen singing along to a medley of Beres hits. Drake conveyed his fondness for the iconic vocalist by retweeting a fan’s declaration that she’d like Beres Hammond to sing at her wedding. Wyclef Jean conclusively expressed the veneration due the bespectacled songster on the outro to his 2001 duet with Hammond "Dance 4 Me," bluntly stating, "All you fake singers, bow down to the legend."

Beres Hammond's most recent single "Let Me Help You" was released on May 3; VP Records says a new Beres project is possibly due by the end of 2024. In between rehearsals for a spate of performances in the New York tri-state area, Beres Hammond sat down with GRAMMY.com and discussed his enduring popularity, his messages to younger artists and the meaning of "brand, Jamaica."

Welcome back to New York City. I was at Reggae Sumfest and I saw your wonderful performance. There’s something extra special about your performances in Jamaica, seeing, hearing different generations of fans singing along to your songs.

What I like most is when the young folks, teens and 20s say, "My mom used to listen to you when she’s in the kitchen working, that’s how I know these songs." They still love them, still sing them. It makes me feel like I came out here to do a job and everything’s been accomplished.

Why do you think your music has such vast appeal among various age groups?

I think it’s the way I present my songs. I make it so easy for everyone to have access. I don’t use Wall Street words; I make it A-B-C. I just do my thing in the simplest manner so everybody can sing it!

You just performed two sold out shows at the Coney Island Amphitheater and the New Jersey Performing Arts Center part of your Forever Giving Thanks tour. So many decades after you started out, that must feel extremely gratifying.

Everyday feels like a new day on the job. I’m giving thanks that I’m in good health and I’ve still got some voice left. All the folks around me, like the band and crew, they’re treating me as if we just started. When you have people around you like that, it’s almost like the journey has just begun.

Have you been working with the same band members for all these years?

For a lifetime, almost. Some have been with me for over 30 years. For the newest members, it might be 10 years.

Throughout your Sumfest performance you intermittently shouted, "brand, Jamaica!" What does that mean?

I was talking about me, what a beautiful brand, but also Jamaica, itself, to the world. Helluva brand! I join the folks that still have Jamaica on the world map as a brand to be reckoned with. Because we nah go nowhere. We deh yah! [We’re here].

I’ve always thought of myself as a brand and upcoming artists should recognize the legacy that’s left here for them. I say "brand" again, to make them understand the role they’re supposed to be playing in what was handed down to them. Be proud of what you’ve got because you are standing on some broad shoulders; be careful how you step on those shoulders.

Coming up in the 1970s and early '80s, whose shoulders did you stand on?

What introduced me to wanting to sing was a few voices including Otis Redding, Sam Cooke, Stevie Wonder, he’s still amazing. I used to love Aretha Franklin and I still love Patti LaBelle. I listened to those voices and said, "Yeah, I would love to sing like them." Then checking on my Jamaican folk, Alton Ellis, Delroy Wilson, hearing those voices, I thought, there must be something out there for me.

Learn more: Remembering Coxsone Dodd: 10 Essential Productions From The Architect Of Jamaican Music

Are there any artists you are mentoring, artists that are standing on your shoulders?

Some of them come up to me and say Father B — they call me all kinda names, Father B, Dada, and they give me some nice accolades. I don’t seek them out, they find me and I always have the right things to say to them, if they ask. Kids still want to learn and being around me, you will learn many things.

Thirty years ago, in 1994, you released your album 'In Control' for Elektra Records. It's still one of my favorite albums.

At that time Elektra went into some merger. The beautiful Elektra crew working with me — some got fired, some went to other places; it was a mess, man. That had a great effect on what the album should have done and really turned me off from Elektra and major labels. This is how people with their big bag of money treat people, come in, push us around. But through the years, I’ve learned that [Elektra] took my music to places that I don’t think I would have reached, so it helped me along.

You continue to have a very successful career, but I can’t help but wonder, had 'In Control' received the push it should have, would your music be better known beyond a reggae audience?

I don’t know, but I know where I stand now and where we are still aiming to go. That never came out of our focus because, hey, the sky’s the limit.

Where are you aiming to go, what are some of the things that you’d still like to do?

I’d like to sing that song that makes the whole world sing along. I’m not sure if I’ve made that one yet.

I hope that my Jamaican brothers and sisters who are making music take it seriously and remember, you’re an influence. Ask yourself, what kind of influence do you want to be to the next generation? Do you want to be the one to make them have a better education? Do you want to be the one that makes them aspire to be leaders? Or do you want to be the one to send them to prison?

Is there any place that you haven’t yet performed but would like to?

People have asked me, what’s my favorite place to perform? I still don’t know. My favorite place is anywhere in the world; once you gather to see me, oh God, that’s my favorite place.

How has the music industry changed in the years that you’ve been in it?

You have to brace to face any new challenge in music. But all I’ve ever wished for is, no matter what kind of changes the music goes through, keep the thing positive so the people can learn. I can’t tell the younger generation what to do. I had my time and did what I had to do; you have to allow them to be themselves, too. Whatever changes the new generation wants to make, I’m there with them; just keep those values and you’re good.

On Jan. 1, 2023, you and Buju Banton put on a very successful concert in Jamaica called Intimate. Any chance you’ll bring that back?

They just talked to me yesterday about it. [Hammond imitates Buju’s resounding voice] "What ‘appen? What are we saying? Second leg? Father B, give I the green light." So, we are looking forward to bringing that back in January 2025.

Read more: Buju Banton's Untold Stories: The Dancehall Legend Shares Tales Behind 10 Of His Biggest Songs

You’ve recorded many songs with Buju and in 2023 you released another collaborative single "We Need Your Love"; an album was expected to follow. Are there any release plans for the Beres/Buju album?

We’ve already recorded 12-15 songs so when them ready, they will tell me. I did songs for Buju and he did songs for me.

Earlier, you mentioned turning on the radio to hear a song that everyone will sing along to; do you listen to Jamaica’s radio stations to hear the latest music?

I listen to talk shows to tap into what the country is doing. You have people calling in, talking about what the prime minister is doing, how many people died today. Music is around me through my kids, my friends. I’m up on everything; without actually listening to it, I’m hearing it.

You have six children; some are pursuing music careers. Tell me about them.

One of them, DJ Inferno, he’s always on the road with me; he plays before I perform, and he mashes up the place all the while. My son Rasheed is in production, trying to establish his own label, he’s ready to start releasing music. One of my daughters, Nastassja, they call her Wizard, she’s a writer, artist, producer. My other daughter, Andrene, is an actress (Andrene Ward-Hammond stars on the CW Network’s "61st Street") and she’s on tour with me looking after my personal needs.

Sometimes I am out here with all six of my children. It’s a beautiful thing. They make me proud.

More Reggae News

How Major Lazer's 'Guns Don't Kill People…Lazers Do' Brought Dancehall To The Global Dance Floor

Living Legends: Beres Hammond On His Enduring Career, Timeless Music & 'Brand, Jamaica!'

Dancehall Legend Spice Reflects On 'Mirror 25,' Her Near-Death Experience & Owning Her Own Vision

10 Artists Shaping Contemporary Reggae: Samory I, Lila Iké, Iotosh & Others

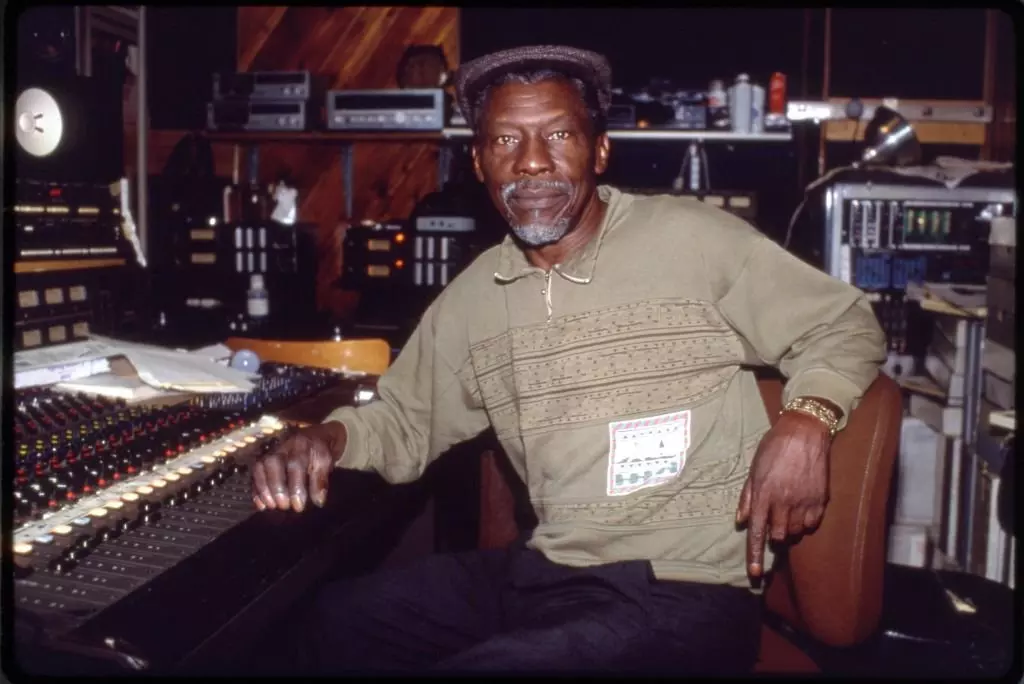

Remembering Coxsone Dodd: 10 Essential Productions From The Architect Of Jamaican Music

Photo: donslens

feature

How Major Lazer's 'Guns Don't Kill People…Lazers Do' Brought Dancehall To The Global Dance Floor

"We thought, if we can introduce what was going on in Jamaica to a more American environment, that would be amazing," Switch says of Major Lazer's seminal debut album.

June 12, 2009: a Friday night at popular Kingston nightclub Quad. Minutes after 2 a.m., the evening’s special guests DJs/producers Wesley "Diplo" Pentz and David "Switch" Taylor will take over the club’s DJ booth and premiere their new collaborative project: Major Lazer.

In addition to the club’s usual Friday night clientele, in attendance are dancehall scene makers and music industry personalities who've come to hear Diplo and Switch’s unique selections and the premiere of the sonic-splicing tracks from their first album under the Major Lazer guise: Guns Don’t Kill People…Lazers Do.

Recorded during a three-week period at the Marley family’s Tuff Gong studios in Kingston, Guns was released on June 16, 2009. The album juggles various sounds into a groundbreaking, genre-blurring collage of samples, audio effects and disparate influences with a significant dose of dancehall reggae’s syncopation, and a primarily Jamaican cast of vocalists.

On the album’s cover art by Ferry Gouw, (reminiscent of the vibrant Jamaican dancehall and dub album cover illustrations of the 1980s) Major Lazer is depicted as a brawny cartoon superhero, "a Jamaican commando who fights the spoils of vampires, zombies, pimps, mummies, and other unsavory forces of evil," according to the album’s press release. Aurally, however, Major Lazer’s ultimate mission was to expand the parameters of electronic dance music and present another avenue of exposure for dancehall reggae and other Caribbean rhythms.

"The intention was to translate how inspired we were by the scene in Jamaica because we drew from a lot of the sounds there," Switch tells GRAMMY.com via Zoom.

The innovative fusion of various electronic music pulses with the island’s reggae and dancehall riddims, as well as the incorporation of dub, took Guns Don’t Kill People…Lazers Do to No. 7 on Billboard’s Top Electronic Albums and No. 5 on the U.S. Top Heatseekers charts. Diplo and Switch further popularized Major Lazer with frenetic performances at raves and dance music festivals around the world.

Guns Don’t Kill People…Lazers Do turned 15 this year. In celebration, Diplo and Switch recently released a deluxe digital reissue of the album, which includes three additional tracks: "Pon De Streets," an alternate version of the original’s album’s hit single "Pon De Floor"; "Nobody Move," with new vocals by Vybz Kartel adapted to a beat created during the album’s initial recording session (found on a hard drive that was locked away in a vault for years); and "Where’s The Daddy," featuring M.I.A., who Diplo once called "the third Daddy of Major Lazer."

M.I.A. originally recorded her "Where’s The Daddy" vocals when she was pregnant (she gave birth to her son in February 2009); as an acknowledgement of that time, she cradles a baby bump throughout the song’s 2024 video.

Diplo, an American, and the British Switch were both immersed in house and other forms of electronic music prior to creating Major Lazer. They merged their cutting-edge, genre-defying approaches on their co-production of M.I.A's chart-topping "Paper Planes"; the song was nominated for Record Of The Year at the 51st GRAMMY Awards.

Diplo and Switch made several beats for M.I.A. that were never used, and decided to record them in Jamaica where, as Diplo noted on X, "the artists were extremely talented, the Jamaican music scene at the time was cutting edge and it was cheap to work there." Those surplus beats coupled with the pair’s ongoing fascination with Jamaica’s dancehall culture led to the creation of Major Lazer.

"It was incredible going to the parties there, whether on the streets or in the clubs, and seeing the interaction between the crowds, the selectors and the deejays," Switch explains. "We were cutting our teeth as DJs and producers and wanted to do something different; we thought, if we can introduce what was going on in Jamaica to a more American environment, that would be amazing, so that’s what we set out to do."

Despite their respective accomplishments as DJs/producers, Diplo and Switch were largely unknown to the Quad’s Friday night patrons at the time of Major Lazer’s debut. They worked hard to win the crowd over with a set that alternated between pounding techno beats, customized dancehall selections, an array of audio effects and a computerized voice that sporadically intoned "Major Lazer." Despite their best efforts, the clubgoers remained indifferent until an appearance by a comical African character calling himself Prince Zimboo (featured on the album’s track "Baby," which incorporates an auto-tuned cry of an infant that’s sampled on elsewhere on the record) thawed the audience’s initially icy response.

Via email, Diplo recalls Major Lazer’s Jamaica debut with brutal candor: "We sucked…basically got booed but Prince Zimboo told a bunch of good jokes and people were happy to have some funny-ass crackers in the club."

Switch, who reflects on that night with greater fondness, remembers feeling "confident that we could play music that no one else had, but could we step into that scene that had inspired us?"

While Switch recalls being nervous about not having a vocalist toasting live on the riddims or hyping up the crowd, he revealed, "more preparation went into that set than either of us has pulled off together or individually. Diplo and I made our own dubs. We took acapella dancehall vocals and put them on our beats, put new vocals on already established dancehall beats and juggled a lot of sounds."

Guns Don’t Kill People…Lazers Do, released four days after their Quad gig, kicks off with "Hold The Line," a crackling spaghetti Western meets surf rock soundscape. An immediate indication of Major Lazer’s preparation and myriad influences, the tune is punctuated by the mantra-like, hi-pitched vocals of barrier-breaking singer Santigold, sharp patois verses from Jamaica’s Mr. Lexx, neighing horses and ringing phones, an eclectic combination designed to make the listener "vibrate like a Nokia."

What follows is the intergalactic throb of "When You Hear the Bassline" (featuring Jamaica’s Miss Thing), the near-psychedelic, cavernous dub resonance of "Lazer Theme" (Jamaica’s Future Trouble), and appealing pop-soca flavored dancehall on "Keep It Goin’ Louder." Artists from the diaspora abound: Queens’ Nina Sky and Brooklyn-based Jamaican Ricky Blaze appear on "Keep It, Goin’ Louder" while Guyana born, Brooklyn raised singer Jahdan Blakkamoore’s exquisite vocals swirl amidst the delay and reverb on the dub-drenched Rasta empowerment anthem "Cash Flow."

"We just wanted to add to the lexicon of dancehall," Diplo writes of the album. "We never tried to elevate or move the sound forward…we just wanted to make something weird."

Out of the weirdness came a significant hit — and the album’s most-streamed track — "Pon De Floor." Created with additional production by Dutch DJ Afrojack, "Pon De Floor" is dominated by a sputtering synth over a marching band snare drum pattern; dancehall’s "Worl’ Boss," Kartel rhymes "baby, get in line, let me see your bestest wine."

"Jamaican DJ crew Chromatic made 'Pon De Floor' a hit in Kingston and it grew from there to the rest of the world," Diplo notes. The track reached the UK Singles Chart, was featured on the "DJ Hero 2" video game, and then attained widespread attention when sampled on Beyoncé’s 2011 hit "Run the World (Girls)."

The song’s stylized video, (think "Pee-wee’s Playhouse" meets Kingston’s now defunct Passa Passa street dance) was directed by comedian Eric Wareheim. The video stars Skerritt Bwoy, Major Lazer’s former hype man, who introduced many viewers to the hypersexualized dancehall "dance" ritual known as daggering.

"'Pon De Floor' was unlike anything that was going on in Jamaica at the time, but it was inspired by the energy of the clubs there," Switch remarks. "I remember going to Hellshire Beach and the DJ at an event there pulled the record up three or four times. Watching the crowd’s reaction, it was like we were vindicated, the song penetrated the real Jamaica scene, people are ok with us; that was a real thrill."

Yet, some weren’t ok with Major Lazer, two white foreigners spearheading a Black Jamaica-rooted album. Protests of cultural appropriation were cited in some reviews, without considering the credentials of the Caribbean artists involved and the benefits many of them derived from it.

"Major Lazer did wonders for me," Vybz Kartel tells GRAMMY.com. "They helped to push me to an audience that normally wouldn’t know Vybz Kartel; with 'Pon de Floor' they could put a name and a face to the song, which definitely gave me a lot of new fans, so big up Major Lazer, every time."

"It was incorrect to think we were doing anything like cultural appropriation, it was journalistic," adds Switch. "We found something that we thought would be appealing and wanted to champion it, expose it. We ended up with Vybz Kartel being on a Beyoncé record, the two farthest apart worlds colliding, and we’re very grateful that we got to bridge that gap."

As Major Lazer’s popularity escalated, Switch decided to leave in 2011, preferring to remain behind the scenes, producing and developing his songwriting skills. "At that time [Diplo] was very focused on the opposite, he was taking the DJ world by storm and it felt like he was fine doing it on his own, collaborating with the people he went on to collaborate with," acknowledges Switch. "But we never really stopped working on stuff together."

In a recent video, Diplo said he considers Guns Don’t Kill People…Lazer’s Do to be "a little bit of punk, a little bit of dancehall, a little bit of pop songwriting" made "really, really fun." "We had nothing to prove, we just decided to put out something that was crazy. I think the album really hit with people because they loved the roughness of it. It had no rules and I think it was very important to break the stereotypes."

Guns Don’t Kill People…Lazer’s Do reminds music fans that dub — created through the innovations of King Tubby and Lee "Scratch" Perry — established the template for remixes by demonstrating the infinite possibilities for deconstructing a recorded work. It also served as a reminder that dancehall reggae, which utilized digitized instrumentation beginning in the mid-1980s, are not only forms of dance music, but have played significant roles in its evolution. Switch adds that the album brought greater attention to dancehall/reggae at a time when international interest in the music had waned.

"I think the album really opened the door for dancehall, not just in dance music but pop music as well. If you listen to what Benny Blanco does with Ed Sheeran, that’s about as mainstream as it gets."

There’s a subtle Jamaican deejay cadence in Sheeran’s vocals on "Don’t" and a lilting, off-beat reggae guitar strum on "Take It Back," produced, respectively, by Blanco and Rick Rubin, for Sheeran’s 2014 album x (Multiply). Sheeran’s 2017 album ÷ (Divide) includes the dancehall inflected hit "Shape of You," which topped Billboard’s 2017 year-end singles chart).

"I’m not saying that wouldn’t have happened without Major Lazer," Switch continues, "but I feel like we oiled the cogs and pointed out a different kind of rhythm that had greater commercial prospects in the pop world, coming from the dancehall scene in Kingston."

More Dance & Electronic Music News

A Timeline Of House Music: Key Moments, Artists & Tracks That Shaped The Foundational Dance Music Genre

Hard Techno Maven Sara Landry Talks 'Spiritual Driveby,' Creating A Safe Space For Emotion & Leaving It All On The Dance Floor

Zedd's Road To 'Telos': How Creating For Himself & Disregarding Commercial Appeal Led To An Evolutionary New Album

10 Cant-Miss Sets At HARD Summer 2024: Disclosure, Boys Noize, INVT & More

.webp)

Machinedrum's New Album '3FOR82' Taps Into The Spirit Of His Younger Years

Photo: Scott Dudelson/Getty Images

interview

Living Legends: Havoc Talks Mobb Deep’s Legacy & The Double-Edged Life Of A Rapper-Producer

GRAMMY.com spoke with Havoc before Mobb Deep drops their final album featuring previously recorded lyrics from the late Prodigy and longtime producer Alchemist on Nov. 2.

Havoc is excited. The Mobb Deep MC and acclaimed industry producer is preparing to film a video with Wu-Tang Clan MC-turned-actor and Internet crush Method Man, and the thought of new music for the masses has him thrilled to pieces.

"This shit is about to be fire," he says enthusiastically. "I can't wait for everybody to check it out."

This single is dropping as part of a larger project with Method Man, which will serve as a tribute to their fallen comrades Ol' Dirty Bastard (ODB) and Prodigy, respectively. But that's not the only new music in the pipeline: after getting the blessing from his late rap partner estate, Havoc will drop the final Mobb Deep album featuring never-before-released verses from the late, great Prodigy, and production by longtime Mobb Deep producer Alchemist, on November 2nd, 2024 — on what would have been Prodigy's 50th birthday.

Born Kejuan Muchita in Brooklyn, New York, Havoc was raised in the Queensbridge Housing Project — the same place that would give the world rappers like MC Shan, Cormega, and of course, Nas — and attended the High School of Art & Design in Manhattan, where he met Albert Johnson (later known as Prodigy). There, the duo would form Poetical Prophets, which later became "The Infamous" Mobb Deep.

Havoc isn't only known for his rhymes — whether as a solo artist, notably on "American Nightmare," where he traded bars with ex-Juice Crew MC Kool G Rap, or as one-half of Mobb Deep. He's also become one of the most acclaimed producers in hip-hop, sitting behind the boards crafting tracks for Lil Wayne, 2 Chainz, and Eminem.

GRAMMY.com spoke with Havoc to talk about his new projects, his legacy with Mobb Deep, and how being both a rapper and a producer is a blessing and a curse.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Let's just dive right into it. Let's talk about your new single with Method Man and your new album.

The concept of the album is to pay tribute to our loved ones who passed away — to Ol' Dirty Bastard, and to Prodigy. We thought it would be cool to do a salute to them. Method Man and I had worked together before this — and seeing that we worked together so well, you know, we decided to do it again.

With the Mobb Deep album: that's been a long time in the making. I wanted to make it years ago, but it wasn't completely my decision. I also needed to work with Prodigy's estate, and they needed time to come to terms with the idea. I gave them as much time as they needed — and of course, we hit a few bumps in the road, but nothing major. We were finally like, "It's time." It's time to continue with the Mobb Deep legacy — to remember Prodigy — and to give the supporters the music that they miss, and love, from Mobb Deep.

Alchemist was one of the people that we worked with when we did the Mobb Deep albums. We were always in contact because we were good friends — and I wanted to have him included to keep up with the Mobb Deep tradition. His inclusion is what our supporters would expect from a classic Mobb Deep album.

I wanted to explore, a little bit, what you said earlier about collaborating with Method Man to both pay tribute to your fallen comrades, and to produce new music. How much of it would you say is paying tribute to ODB and Prodigy, while educating young heads about their history — and how much of it is the "new sound" that's representative of where you two are in your careers right now?

It's equally a bit of both. We're talking about where we're at right now in our careers and our lives — we're both older now. Method Man really doesn't like to curse too much, and I understand — but I'm on there, talking my talk, as usual. Nonetheless, Method Man is in the greatest space he's ever been in, in his life.

You also have a great deal of influence in hip-hop as a producer. Some may go so far as to say that you're one of the most iconic producers of all time. From your perspective, the two-fold question is this: would you say your impact is more felt as a rapper, or as a producer? And is that your legacy, in this industry, and how you'd like to be remembered?

I believe I'm better received as a producer than as a rapper — which is kind of like a gift and a curse. It doesn't bother me too much, but I pour a lot of my heart into writing — I started as a rapper first, and did production later.

I don't know how the transition happened — how I became better known for my production work more than my rapping — but I'd love for people to know how rapping is indeed my passion, because, to me, it's tough being a rapper that writes his lyrics and does his production at the same time. That's a big leap. If you could ask any rapper that same question, they'd tell you that it's a lot to do.

I'm happy that I'm being recognized, but I'd like respect for my pen game.

Let's go back to the early years — 1991, and your appearance in "Unsigned Hype" in The Source when you started to make headway in the mixtape scene in New York. Did you recognize that you were tapping into something special, or did that recognition come later?

I think we knew we tapped into something special, whether people recognized it at the time or not. So, when the recognition from a broader audience came along, it just affirmed what we knew all along.

With "Unsigned Hype," that opened the floodgates for us. One thing led to another, we signed our first record deal, and that's when we started releasing our singles and working with Wu-Tang Clan and other artists. That's when we took hip-hop by storm. So we knew that we'd tapped into something special, and we hadn't even finished the full album yet.

Read more: The Unending Evolution Of The Mixtape: "Without Mixtapes, There Would Be No Hip-Hop"

Where did your mind go with it, once you realized that? Did that change the way you made music, from that point forward?

I believe so. We had a unique recipe, and we followed that recipe for the rest of our career. And we knew that people wanted a specific sound from us, and they wanted us. They didn't want Nas, or Big L, or even Biggie. They wanted Mobb Deep. So we never tried to be like anyone else — we just gave them us, and that was the winning formula.

How did you handle being drawn into the intense East Coast-West Coast feud, particularly after 2Pac named you in 'Hit 'Em Up'?

We were ready for it. We were prepared for war. Look, hip-hop is a contact sport. It is very competitive. So I just looked at it as a rap battle. At the time, I looked at it and thought, "Well, maybe when we see each other in person, there will be a little scuffle." We're artists — we might rap about certain things, and speak about political issues and life in the hood, but at the end of the day, we're entertainers.

I thought people had more respect for human life. I never thought it was a life-and-death game. But when it became a life-and-death game, it shook the core of my existence. I didn't like it at all. And I don't believe that anybody involved — not Pac, not Big, not anybody — deserved to lose their life over some rap beef.

It made me paranoid, and I believe I still have PTSD over it. Biggie Smalls and I share the same birthday. So it hits closer to home for me.

Did you ever get a chance to squash the beef with Pac while he was still alive?

Not at all. He died in the middle of our beef. We put a record out called "Drop a Gem on 'em" in response to "Hit ‘Em Up." We put the single on the radio — it was clear we were dissin' Pac — and, not even seven days after we first dropped the single, we found out he got shot in Vegas. And we pulled the record from the radio — purposefully.

It wasn't until maybe 20 years after the fact that we got a chance to speak with Snoop Dogg. I never thought I'd get a chance to chill around West Coast rappers, but time heals everything. Now, I'm friends with Tha Dogg Pound. I'm friends with Snoop Dogg. I'm in Los Angeles all the time. But that was way down the line.

You have to understand that when it came to Snoop, we didn't have any "beef" to squash, especially after Biggie and Pac were murdered. Once we started hanging out with West Coast artists, we knew that beef was over — and I believe the media hyped it up more than it needed to be, to be honest. No life is worth losing over some rap beef.

For a brief period, you and Prodigy weren't on the best of terms. You even engaged in a bit of a Twitter (now X) back-and-forth that left many fans — myself included — bewildered. Looking back on all of it now, what was the issue at hand, and how did you guys resolve it?

Prodigy and I have known each other for so long, we're brothers. Internally, differences were brewing — but when you're brothers, you're going to get into arguments and disagreements, but at the end of the day, you still love one another, and you're going to work things out.

It was never meant to spill over into the public. And I take responsibility for that. I expressed myself publicly at a time when I shouldn't have been near any electronic devices, you know what I'm saying? I was drinking, and you're emotional when you're drinking — but when I was sober, I realized what I was doing was wrong.

I'm not going to go on record to say what we were beefing about, but at the time, I thought it was valid. Prodigy and I squashed it a year later, though — we knew it was bad for business, plus, we'd known each other for too long to let it go on like this.

Let's touch a little bit on the G-Unit years. There's a lot that you did with the label — and you'd already had that relationship with 50 Cent before the signing. So, tell us what you learned during the G-Unit era about the business, hip-hop, and so on.

I'd begun working on a solo album, and the late Chris Lighty was my manager. He'd told me about this young dude named 50 Cent, and I heard some of his stuff and I was blown away.

I'd told Lighty that I wanted to work with Fif, and 24 hours later, I had him in my studio. At the time, he told me how much he'd admired Mobb Deep, while also hinting that he was considering working with Eminem and Dr. Dre, as they'd shown some interest. He'd even asked me what I thought he should do!

Well, my solo album never came out. Years later, when Mobb Deep got shifted around from label to label, and got dropped from Jive Records, Fif had already sold 10 million records with Get Rich or Die Tryin'. And I didn't believe that he'd even remember me — but when he heard what happened, he called me up and said he wanted to sign Mobb Deep.

Prodigy initially didn't want to do it, but he changed his mind once he sat down with 50 Cent. The rest, as they say, is history. I was so pleased to be down with a crew that had sold so many records. But a lot of our fans, at the time, was hatin' on it. They thought we'd sold out.

I don't even know where to begin with this, but: let's talk about Prodigy's death. It was a gut punch to me, and I can't imagine how it was for you. Where did you find the resolve to take on the responsibility of being the torch-bearer for all things Mobb Deep once Prodigy was gone?

I found it while I was thinking about Prodigy. I was thinking about him, and I was saying, "If God forbid, the shoe was on the other foot, he'd be moving forward." He'd be celebrating the Mobb Deep legacy. I don't think he'd want Mobb Deep to fall to the wayside. He'd be missing me like crazy, but he'd be taking Mobb Deep to the next level.

With that, I found the resolve. I then thought about the supporters, and how they deserved one last Mobb Deep project. And I'm gonna make sure that happens because I don't want to be the one that fumbled the ball just because Prodigy isn't here. I'm the one who has to make sure that the masses hear it.

And this is the last Mobb Deep album. At least, for now. There are still plenty of Mobb Deep verses to go around, but that's not for me to decide. I spoke to the estate about this album, and this album only. That's where my focus is.

So, after this final Mobb Deep hurrah, what is next for Havoc?

There are a lot of things I want to get involved with — documentaries, film scoring, getting my label off the ground, mentoring young artists — that I don't think I'll ever be bored. No, there won't be any Mobb Deep anymore, but there's still Havoc. And that's my legacy.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Khatia Buniatishvili Plays "Mephisto-Waltz No.1"

Peanut Butter Wolf Talks New Campus Christy Album & What's Next For Stones Throw

Warner Music Group's Paul Robinson To Be Honored With 2025 Entertainment Law Initiative Service Award

Your Vote, Your Voice: 6 Reasons Why Your GRAMMY Vote Matters

JOHNNYSWIM Reveal The Mic That Defines Their Sound

Photo: Corine Solberg/Getty Images

interview

Living Legends: Lionel Richie On 'The Greatest Night In Pop,' "American Idol" & The Evolving Essence Of The Music Industry

"When I wrote those lyrics…it was exactly the feeling of where we are now as a world," Lionel Richie says of "We Are the World." In a wide-ranging interview, the four-time GRAMMY winner discusses the iconic charity single and his career to date.

Whether explaining to his parents that the Commodores would be the "Black Beatles" or writing a mega-smash charity single in a single evening, a young Lionel Richie has something of a mantra: "Everything was possible."

When the now-iconic "We Are the World" first hit the airwaves in 1985, listeners surely were awed at the thought of so many legends in one room. Performing under the banner of USA for Africa, the track featured everyone from Ray Charles to Stevie Wonder, Michael Jackson to Bruce Springsteen, Cyndi Lauper to Tina Turner, and sold more than 20 million physical copies to raise money for African famine relief. The song’s recording was documented and encapsulated in the recently released documentary The Greatest Night in Pop.

Richie is the glowing supernova of musicianship creative wrangling at the core of the song and film. "Part of the whole magic of the song was to know the back side of it," Richie tells GRAMMY.com, hinting at the open, warm tone that has characterized his entire career.

Richie's sterling vocals and immaculate songwriting first rose to international prominence in his time as co-lead singer of Motown heroes the Commodores, for whom he wrote songs like "Easy" and "Three Times a Lady." Richie expanded his already endless pop charm as a solo artist, topping charts and winning countless acclaim and listeners’ hearts alike with songs such as "All Night Long (All Night)," "Hello," "Say You, Say Me," and "Dancing on the Ceiling."

When the concept for creating a track to raise funds and awareness for African famine relief was first broached by legendary artist and activist Harry Belafonte and manager Ken Kragen, Richie was tapped to write the song with Michael Jackson. The duo pulled an all-nighter to write the track a day before the first recording session — which also happened to be the very same day Richie was to host the American Music Awards, his first hosting gig on television. (Richie has become a fixture on TV, including his recent stint as a judge on "American Idol.")

Throughout his myriad roles and projects, Lionel Richie remains both incredibly professional and one of the warmest personalities in the music industry — not to mention a captivatingly brilliant musician and four-time GRAMMY winner. GRAMMY.com caught up with Richie to discuss the making of "We Are the World," finding himself in the room with every one of the icons he admired, and the continued need for hope and positivity 40 years later.

I have to tell you, I re-watched The Greatest Night in Pop this morning, and it is no less incredible after another watch.

Thank you. It's one of those moments in time. Just to see the positivity, number one, and number two, the impossibility of how we pull this off. Trying to do that today, you would just want to drive yourself crazy. There's no way today you can keep a secret.

Of course you’d have a leak, and is everybody going to show up? There’d be too many egos. "Leave your ego at the door?" You won't even leave your ego at the phone call.

The whole business has changed. But in the documentary, you really feel the weight of the challenge and the massive scope of opportunity. During that time, were you completely confident or or was there a constant worry that it might fall apart? Perhaps you had so many responsibilities that success and failure didn't even cross your mind.

You know what's so brilliant about being young and naïve? Everything has possibilities.

I look back on my career, when I walked in that door that fateful day that I was going to tell my parents that I was going to drop out of my last semester of my senior year and go full time with the Commodores. And I said, "Mom, Dad, we're the Black Beatles. We're going to take over the world." That takes a lot of just innocence and naivety and youth. Everything was possible. With "We Are the World," we were all kind of sitting there going, "What can we do [to make this work]?" And as we started calling up people, it just became "I'm in." "I'm in." "I'm in."

Of course, Ken [Kragen, manager] didn't tell us that he was making all these phone calls. We just thought it was going to be Quincy [Jones], Stevie [Wonder], Michael [Jackson], and myself. And Harry Belafonte. And the next thing we know, we've got all these artists waiting for the song that we haven't written. [Laughs.]

I think that was so wonderful that you didn't have that level of project in mind. Whilst naivety is part of the process, I feel like if you weren't able to be so in the moment, the song may have come out differently.

I always believe that if you have too much time to think about something, you're going to mess it up. I said yes to something that I didn't realize I had no time to do. This is my solo time in life. I've just left the Commodores; I'm hosting the American Music Awards. I've never done that before.

And of course, the pressure was there as well. Who is this kid to host this show alone? Alone, alone, not with two or three hosts. There was a lot of doubt as to whether this kid could do this or not, you know. As time went on, it just became another part of the story. And I've always believed I'm very good at getting myself into crap. And then I have to work my way out of it.

You're a good swimmer.

[Laughs.] Yeah. And so this thing just started evolving. "Okay, Lionel, what about the rehearsal for the American Music Awards?" And I go, "Oh, that's right. We have to rehearse."

The rehearsal time was also the time we had to cut the track for "We Are the World." And then we have to write the lyrics. Meanwhile, I have to rehearse [for the AMAs]. But, you know, I look back on it, honestly, and it was just divinely guided. Sometimes if you just have a chance to sit back and think about the intricate parts of it, everyone showed up at the right time to do the right thing.

It was astonishing to think about how many roles you had in that record coming to life. You were a writer, a singer, a producer, a coach, a psychiatrist, a guide. And you continue taking on so many different types of projects and roles to this day.

Well, let me tell you what makes things like "We Are the World" happen. I won’t just sit here and talk about, you know, how I did it. That was a room full of pros, you follow me? Quincy Jones, master producer, master arranger. I asked Quincy a very important question one time. I said, "How in the world did you deal with all of those various personalities and stuff?" He said, "What do you think an arranger does?" I said, "What do you mean?" He said, "What do you think I do for a living? My job is to organize chaos." In other words, the woodwinds are playing one thing. The brass are playing something else. The violins are playing something else. And all together it sounds like a song. Well, he was the master of that.

When you bring in artists from all different genres, each one of those artists, A, had their own sound, and B, knew how to deliver it. So all we had to do was kind of set the stage for them to do that half a line and pull it off. But behind the scenes, look at Humberto Gatica. He is a great engineer. How many tracks can you mess up? He had 99 million tracks and all of a sudden we couldn't have a delay [in the schedule]. There was no delay possible. I think what made my part of this whole thing, I was just putting out fires. Wherever there was a fire, like, "Okay, Bob Dylan, you need to go see Stevie Wonder. [Laughs.] And Huey Lewis, you just need to calm down." He thought he was just going to come and hang out.

Oh, Huey is such a fun guy!

Huey was going, "I'm going to sing whose part?" [Laughs.] It made everybody honest. I said, "Okay, Quincy, how are we going to pull this off? Is everybody going to go in the vocal booth one by one to do their parts?" He said, "No, no, no, no. We're going to put them in a circle and let them sing to each other." And I said, "What?"

He said, "I promise you, they'll be perfect on every round." Because when you're facing each other, there is no "Give me another take" or "Give me two more takes" or "Let me warm up." Just the fear factor of facing every artist you've ever admired in your whole life. There's Ray Charles over there. There's Kenny Rogers over here. There’s Diana Ross.

And Tina Turner!

And Bruce. And Billy Joel. We were, basically, the youngsters in the room. There's Michael. We'd all been around in the business a long time, but we'd never just been in a room to face each other.

So I think what was so amazing is when we went around one time at that piano, just to hear how it was all going to sound, that's when we knew we've got something. It was going to be a good sound.

Fitting all those different sounds and voices is such a beautiful achievement. It really makes you stand out, that ability to guide people and projects so naturally. It really makes sense that you have this continued role as a statesman of the industry, even down to your work on "American Idol."

You know what was so great? What we all heard back then, and what still rings true today, there's a word that the world needs right now. It's called hope. [When] that song came out 40 years ago; it was this amazing light, this beacon of hope. People started going, "Ah, okay, you're right. We need to care about each other."

It's one of those aha moments when you realize that a group of us got together and actually made that statement. As world-famous artists, we took all of our light as celebrities and entertainers and songwriters and shined it on hunger and starvation in the world. It was just a great statement.

I’m sure you have countless admirers who come up to you and talk about your work, but can you share some things that listeners have told you about that song in particular?

What I loved is when you start getting the 7- to 12-year-olds [saying] "We sing ‘We Are the World’ in our school!" Then that segues over to "American Idol."

When I first met Bao [Nguyen], the director [of The Greatest Night in Pop], he scared me to absolute death because I'm thinking that we're going to bring in a well-seasoned director from 1983 or 1984. He says, "I was two years old when that song came out in Vietnam." [Laughs.]

A lot of people just heard the song, but they didn't know the background [or my role in it]. So they didn't know that Michael and I wrote the song together. They knew I was maybe in the song, but they didn't know to what degree. I’m having a lot of people just come up to me with the sheer discovery. "Oh, my God, I didn't even know you did it."

"Where have you been?"

It really tells how blessed we were, because think about this now. All of us [working on the song] went on to have careers, major careers; that was the beginning of our big explosion.

What I love the most, I think, is just the fact that what Michael and I set out to do with that song was we wanted not a song, not a hit record. We wanted an anthem. We wanted a song that will stay around generation after generation, year after year. When people ask me right now, "God, Lionel, you need to write another song, because we need it so much today." And I go, "Play the song again."

It's so relevant. Absolutely.

Everything I wanted to say 40 years ago, I would write today. In other words, history just keeps repeating itself over and over again. And everyone keeps thinking you need something new. No, the whole song said everything.

But then when was your last all-nighter? Because that was a pretty epic all-nighter that you had that night.

[Laughs.] That was an "all-two-dayer"! That was the day before rehearsing for the American Music Awards. You then wake up and then actually start rehearsing from 7 in the morning at the Shrine Auditorium 'til the show started, and then to leave there at 11 o'clock at night, 12 o'clock at night. I forgot to also mention [that] I was not quite prepared for hosting, because this was my first time doing it. But also, I wasn't ready to win. [Editor's note: Richie won six times at the AMAs the year, including Favorite Pop/Rock Male Artist.]

It was a lot of moving parts. But the beautiful part about it was, I think the dedication and the hearts of each of those artists. Everybody came to shine their light on this issue. And the brilliance of it is, it worked.

What's something positive that you've been feeling about music lately?

Well, here's what's happening. I went into "American Idol" thinking, There is no possible next level of artistry. Because I've been there, done it, I've seen it. This is my eighth year coming up on "American Idol" and talent keeps showing up. Unique talent keeps showing up. Writers keep showing up. And I think what I'm looking forward to is when the industry can now keep up with the talent. Because we're overflowing with talent.

The problem now is, how do we get all of this talent recognized around the world? I mean, when I get to the top 20 on "American Idol" literally, I could start a record company on the top 20. We're throwing off such amazing talent. You constantly have to think, Okay, what are we doing?

For example, Jennifer Hudson did "American Idol," and she was let go at number nine, and then went on to become a massive star. This year coming up, Carrie Underwood won "American Idol" and here she is now coming back as a judge and mentor.

My situation now is, how do we get more of this talent recognized to the world? We were very fortunate back then because everything back then was global. There were only basically four different networks you could deal with. And then if you want to go outside of that, it's called BBC. What the internet did was great in terms of everybody's on it, but it also made it a big soup. You've got so many different angles and avenues. How do you focus your audience?

I think what's going to happen in the next couple of years is technology is going to be able to help us in a lot of ways. Because there has to be a new model that's going to be able to showcase not only the artists, but then there's the writers, the producers, the engineers, the musicians.

Yes! More focus on the collective who create the art. Where are the credits? I want my liner notes.

Exactly! I don't want to be the guy who’s like, "Bring back the good old days," but…

I think a lot of people are saying the same thing, no matter what age they are.

I couldn't wait to read the liner notes. Who's on that record? Oh my God, that writer was on there. Oh my God, that musician was on there. So-and-so sat in on the session. Part of the whole magic of the song was to know the back side of it, what was really happening. There's a lot that we can discover going forward, but there's a lot that we are losing from the past that I would like to bring up. Because we're not really giving credit where credit is due.

We need time. But we also need the advocate, the voice behind a message, which you are so clearly great at. You saw darkness in the world and put out a song. We know that song is not going to fix whatever the problem is, but the music becomes a comfort. What is that song for you that brings you to the place where you're feeling downright comfort?

I don't want to be the one to go that route, but my go-to for calm is "Easy Like Sunday Morning" ["Easy", from the Commodores’ 1977 self-titled album]. I know that it's always best when you use somebody else's song, but I wrote that song in a state of just that. I wasn't quite sure. I wasn't aware. The other song would be "Zoom" [from the same album]. The lyrics to that song basically sums up exactly where we all are. There's a place we'd all like to go and just hide for a moment to get away from all this craziness. I use those two songs as my mantras just because of the message that it gives.

That duality of "I'm telling you my story, but also we're all sharing this." I love it.

I think the entry of that was, "I may be just a foolish dreamer, but I don't care. All I know is my happiness is out there somewhere." We're all looking for that silver lining, that horizon that we've never seen before. When I wrote those lyrics, I must tell you, it was exactly the feeling of where we are now as a world. Because it was confusing. Think about it. This is the early ‘70s, coming out of the ‘60s, the craziness of Vietnam, and as a kid, what's out there for us? I don't know. What's the possibilities? We're not sure. And so here we are again, yet again faced with this survival of how do we stay sane in this world of insanity?

And how do we feed each other with things that feel nourishing?

What I love about the music business is that what determines a real hit record is when people walk up to you and go, "Lionel, I felt the same way." Now, that means you start realizing that, "Yes, I wrote a love song, but those words helped everybody else. That feeling that I felt is the feeling that everybody else felt."

So it's a confirmation that we're all human. We're all feeling. There are moments of happiness. There are moments of tragedy. And we're all doing this in the same world of trying to cope. And so I always say at the end of the day, there's got to be this common bond of humanity and mankind. There's got to be a thread of hope. Otherwise, we've lost the plot completely.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Khatia Buniatishvili Plays "Mephisto-Waltz No.1"

Peanut Butter Wolf Talks New Campus Christy Album & What's Next For Stones Throw

Warner Music Group's Paul Robinson To Be Honored With 2025 Entertainment Law Initiative Service Award

Your Vote, Your Voice: 6 Reasons Why Your GRAMMY Vote Matters

JOHNNYSWIM Reveal The Mic That Defines Their Sound

Photo: Theo Wargo/Getty Images

interview

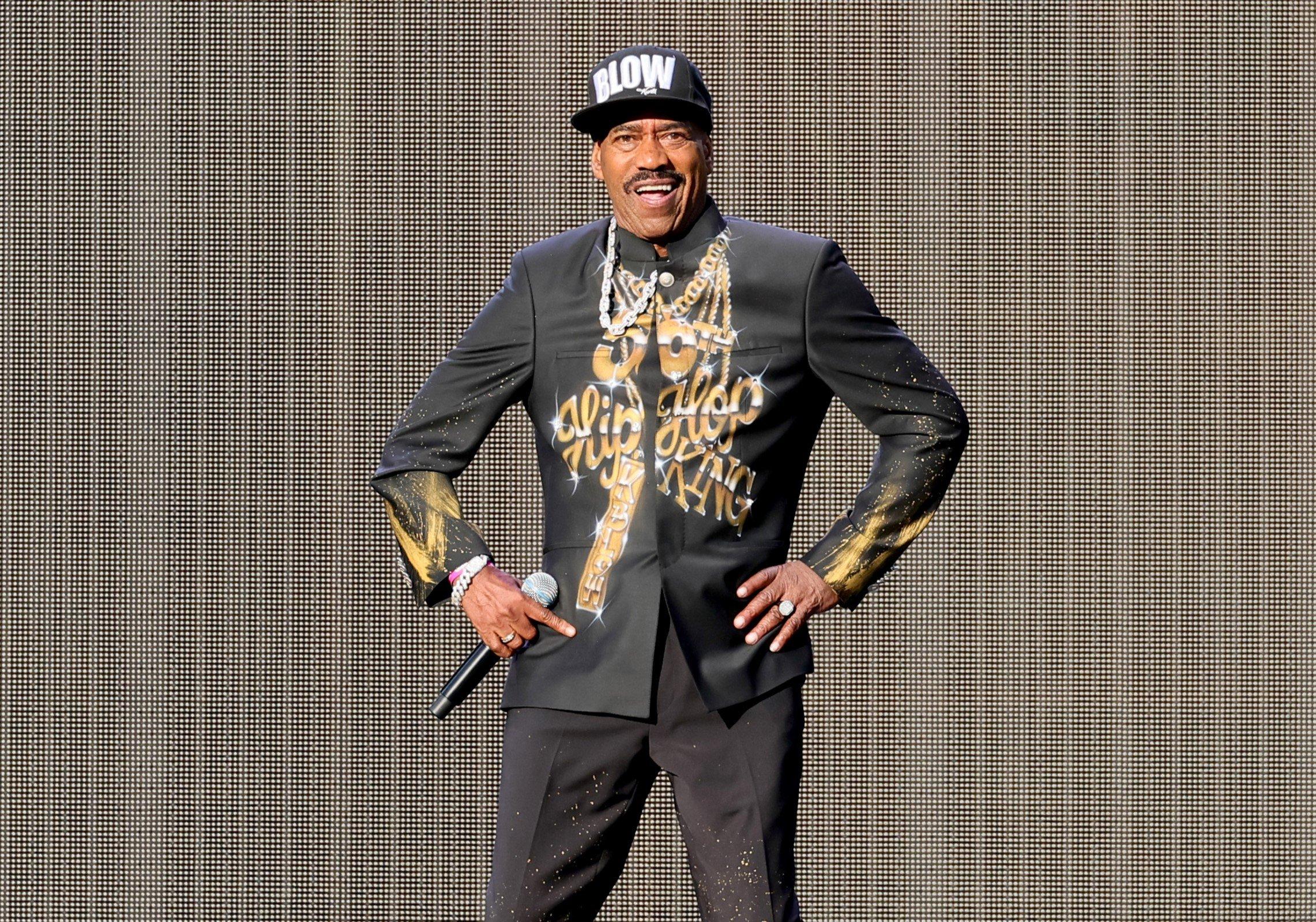

Living Legends: Kurtis Blow On How Hip-Hop Culture Was "Made With Love" & Bringing The Breaks To The Olympics

More than 40 years after he became hip-hop's first commercial breakout star, Kurtis Blow is still moving the culture forward. The rapper and OG B-boy reflects on hip-hop’s rich history, and the impact of seeing hip-hop represented at the 2024 Paris Games.

On the eve of the first-ever Olympic breakdancing competition, hip-hop legend Kurtis Blow was thrilled. It was the first time one of the core elements of hip-hop culture had reached such a global stage.

Alongside DJ Kool Herc (whose breaks provided the soundtrack for B-boys and girls), Blow is credited with popularizing breakdancing. The rapper began breaking as a teenager in the early 1970s, as part of the Hill Boys breaking crew — named for the Sugar Hill area of Harlem where Malcolm X first started his galvanizing pro-Black movement —

And while the International Olympic Committee decided to remove breakdancing from the 2028 Olympics, Blow is unbothered. As far as he’s concerned, his legacy and the legacy of breaking itself is all but set in stone.

"It was definitely something special," Blow tells GRAMMY.com. "And I wasn’t the only one who realized it at the moment it was happening."

Born Kurtis Walker, the Harlem-based Blow began DJing when he was just seven years old. In 1979, the 20-year-old's "Christmas Rappin’" sold over 400,000 copies and turned the up-and-comer into a household name. But it was his follow-up single, 1980’s "The Breaks," that helped launch a whole new genre: rap music. "The Breaks" became the first hip-hop album to receive a gold certification from the RIAA, and proved that Blow wasn’t just a one-trick pony.

Kurtis Blow proved to be immediately influential on the then-nascent rap scene. When Rev. Run of Run-D.M.C. started his career, he billed himself as "The Son of Kurtis Blow" to give him an air of credibility that helped propel the hip-hop trio into the pop culture stratosphere. But Blow's influence didn’t begin and end with his "adopted son": Everyone from Russell Simmons to Wyclef Jean has worked with Blow, and he has been sampled by Nas ("If I Ruled The World" is all but an interpolation of Kurtis Blow’s song of the same name), KRS-One and many others. In fact, more than 100 songs have used samples from "The Breaks," and nearly 1,500 songs have used a sample or an interpolation from Blow’s discography.

Learn more: Essential Hip-Hop Releases From The 1970s: Kurtis Blow, Grandmaster Flash, Sugarhill Gang & More

Kurtis Blow was also one of the first rappers to sign to a major label (Mercury Records) and was the first rapper to be a multihyphenate (in addition to his music, Blow worked as an actor on films like In a Dark Place and California Dreamers, and was the musical coordinator for the legendary hip-hop film Krush Groove). Blow continues to work steadily in hip-hop today, though he eschews the legendary breaking parties in favor of cultural events that offer a new glimpse into the culture he helped create.

To wit, Blow is performing with The Hip Hop Nutcracker, in which Tchaikovsky’s classic score is set to breakdancing and modern hip-hop dance; the emcee will perform a brief set to kick off each show. A nationwide tour kicks off in Southern California in November and concludes at the end of December in Durham, North Carolina.

Kurtis Blow spoke with GRAMMY.com about the importance of bringing breaking to the Olympics, reconciling his ministry with modern hip-hop’s message, and his four-decade legacy.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Breakdancing has been a huge part of hip-hop culture for many, many years — and it’s long overdue to be recognized on a global scale like the Olympics. What are your thoughts about seeing this movement that you started getting this kind of recognition?

This whole culture that we call hip-hop started back in the 1960s. With the Civil Rights movement, community organizers, and government officials all debating about something so basic: the right to all be seen as equal and free. It was a traumatic time, you know? But we had music that was so relevant to the whole movement.

By the time the late 1970s and early 1980s came along, everyone was trying to escape all of the traumatic racism that was still going on. And music became our escapism. That’s where breaking came in: everyone was just trying to mimic James Brown on the dance floor. You’d see one guy doing his thing, and everyone would form a circle around him. Pretty soon, someone else would join the circle and challenge him. And before you knew it, there was a whole competition — and whoever won became the most popular in the club.

That kicked it all off. To see it recognized on such a large scale just reaffirms, to me, that this hip-hop culture of ours was made with love.

There were breaking films such as 1985's 'Krush Groove' that were completely revolutionary in that it gave everyone — not just those within the culture — a view into the world of hip-hop, and suggested what it could become. At the time, you were becoming the first commercially successful rapper and one of the pillars of what would become the New York sound. Were you aware that you were on the precipice of something revolutionary?

I don’t want to call myself a visionary or anything like that, but I did know that this was something special, because I saw how quickly it spread around different boroughs in New York City.

From Harlem and the Bronx, and then over into Queens, Brooklyn, and even New Jersey, it was amazing to see everyone just gel around that whole hip-hop scene. As I said before, we all needed that escapism, you know? Forget about your troubles, just come and dance.

With me being in Harlem, right down the block from the Cotton Club and that whole mindset around dancing becoming America’s pastime — just coming from that era, where we had to go to the parties to have a good time — [I knew] that we had created something that would outlast us.

Not only did you attend divinity school, but you are also an ordained minister. How do you bridge those two aspects of your life and how do you reconcile being a rapper with being a minister?

That is such a great question, and thank you for asking.

It’s very simple: God is the Creator. God created hip-hop. We have to start with that, right here. God gave us the talent to perform the music; he gave us the passion to want to spread the music to the masses. He gave us the desire to say, "Hey, come take a look at me! God has blessed me with this — can you do this?"

Now, when you talk about the actual elements of hip-hop — that is, the emcees, and the message that we bring — it’s crucial to understand that we are commanded by God to uplift our community and to show them love. This is the actual essence of hip-hop: peace, unity, love, and just having safe fun.

My mission is to believe in the faith that God is real, and God is in the miracle business. I have seen nothing but miracles for the last 45-50 years in this thing called hip-hop. And it’s important to understand that God is in the mix, and we are all blessed by the common denominator known as hip-hop. It should be our mission to get that back.

As for what’s going on today — the nature of the lyrics, the gangster rap, and all the violence — it didn’t really start out that way, did it? And if we can inspire the future for our youth, then we’ve made a difference. Because the future is in their hands, and we need to inspire them.

But, as a counterpoint, times are different today. And what these men and women are speaking to may not necessarily be destructive — rather, there could be a case made where they’re merely being street poets, and telling the reality of life as they see it. What advice would you give to those people who are telling a different story than the one you told all those years ago?

We are called to be these soldiers, warriors, servants, and communicators. So I understand their reality is different, you know? The world is upside down. The kids out there are just telling it like it is. They’re communicating their reality.

But I think that we should not only communicate how it is, but how it could be. And how it should be.

Think of how different it would be if they also gave some inspiration for a positive future: "Yeah, we goin’ through this, we goin’ through that, but with God, you can overcome all of that. With prayer, you can have miracles, and blessings, come down."

Even if you just understand the nature of the reality that we’re going into right now — things like mass incarceration, the drug epidemic, gun violence, the war profiteering off of Black and brown bodies — it falls upon the shoulders of the elders of this community, this hip-hop movement, to inspire and communicate the possibilities to the younger up-and-comers.

They need to understand that they are the product of royalty. They are the descendants of kings and queens of Africa. They need to honor themselves and honor their ancestors, accordingly.

The culture of hip-hop isn’t just about the music. It’s about fashion, slang, cars, the sports — if you think about it, anthropologically, hip-hop is a civilization onto itself. But, as with all things, so much of it has been co-opted and mainstreamed. How do we bridge the divide between the originators and the colonizers?

Only love can bridge that gap between the ages, the races, our government — the diversity of all these different countries — you know, it needs to be all love.

This is what it’s going to have to take for us to change our present reality. And I feel that in hip-hop, that is the key to that future. The OG’s had the right mindset: peace, love, unity, and having safe fun. We need to get back to that.

When you look back on your career and the legacy you leave behind, how do you want to be remembered?

I remember being in divinity school at Nyack College in New York, and the professor asked the whole class the same thing. And I thought about it for a while, you know? I thought about being remembered as a pioneer of hip-hop — an OG breakdancer — a DJ when I was just seven years old — and an incredible educator.

But what stuck with me was being known as a man of God. That’s it. Because that encompasses everything that I have been through and survived. All of my success, and everything you know about me, comes from God — and to God be the glory.

Latest In Rap Music, News & Videos

Kendrick Lamar & Imagine Dragons' GRAMMY Mashup

Duckwrth Covers Coldplay's “Clocks” | ReImagined

10 Juice WRLD Songs That Showcase The Rapper's Legacy: "Lucid Dreams," "Robbery" & More

10 Facts About MF DOOM's 'Mm.Food': From Special Herbs To OG Cover Art

6 Indian Hip-Hop Artists To Know: Hanumankind, Pho, Chaar Diwaari & More