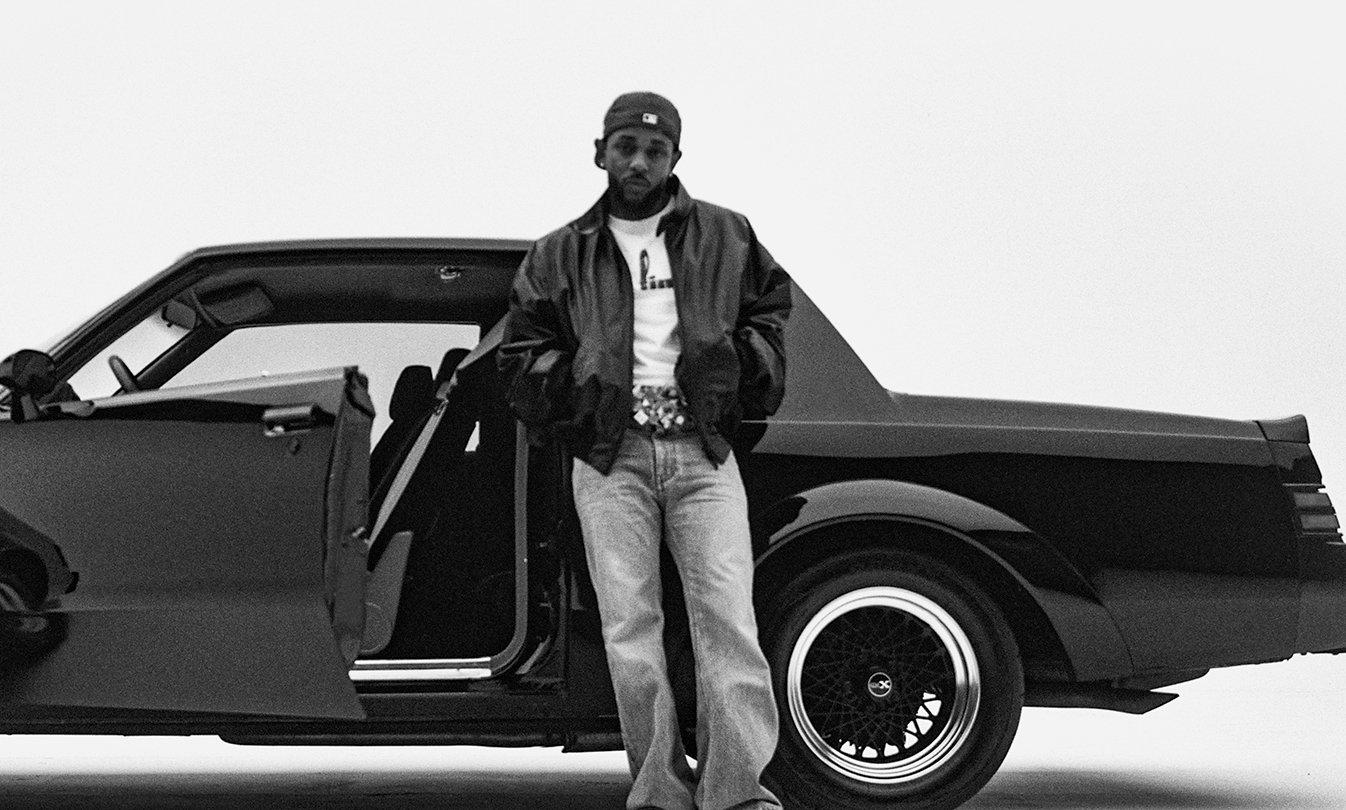

In between Good Kid, M.A.A.D City and To Pimp A Butterfly, a 2014 trip to South Africa changed Kendrick Lamar. As he toured the country — visiting historic sites such as Nelson Mandela's jail cell on Robben Island — his worldview broadened, and so did his music.

The trip led Lamar to scrap "two or three albums worth of material," according to engineer/mixer Derek "MixedByAli" Ali. Lamar wanted to make music that reflected the sounds of his upbringing in Compton, Calif. He began to listen to the likes of Sly Stone, Donald Byrd and Miles Davis. Eventually To Pimp A Butterfly took form, incorporating elements of jazz, funk, soul, spoken word, and hip-hop.

"I wanted to do a record like this on my debut album but I wasn't confident enough," says Lamar.

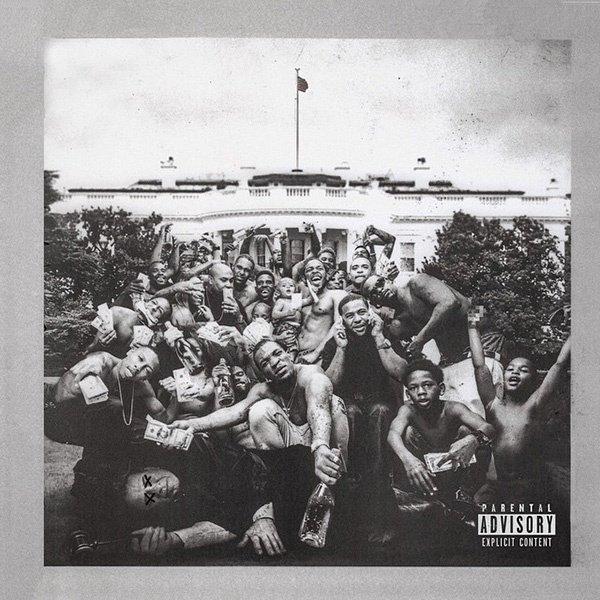

Lamar garnered 11 GRAMMY nominations, including Best Rap Album and Album Of The Year. Following, Lamar and key collaborators tell the story of To Pimp A Butterfly.

Kendrick Lamar (artist): The title grasped the entire concept of the record. [I wanted to] break down the idea of being pimped in the industry, in the community and out of all the knowledge that you thought you had known, then discovering new life and wanting to share it.

Sounwave (co-producer): I remember he took a trip to Africa and something in his mind just clicked. For me, that's when this album really started.

Lamar: I felt like I belonged in Africa. I saw all the things that I wasn't taught. Probably one of the hardest things to do is put [together] a concept on how beautiful a place can be, and tell a person this while they're still in the ghettos of Compton. I wanted to put that experience in the music.

Derek "MixedByAli" Ali (co-engineer/mixer): [Lamar is] a sponge. He incorporated everything that was going on [in Africa] and in his life to complete a million-piece puzzle.

Lamar: I was on tour with Kanye [West] and I had Flying Lotus with me because I wanted to work on the bus studio. He would make beats and it was one particular beat that he forgot to play. He skipped it but I heard about three seconds of it and I asked him, "What is that?" He said, "You don't know nothing about that. That's real funk. … You're not going to rap on that." It was like a dare.

Thundercat (co-producer): ["Wesley's Theory"] started with Flying Lotus and I sitting on the couch in front of the computer analyzing George Clinton. He became the fuel for creating. I was really blown away that Kendrick was so into that song.

Sounwave: That song is the album cover.

Lamar: I had to find George Clinton in the woods, man. He was somewhere in the South and I had to fly out to him. We got in the studio and just clicked. Rocking with him took my craft to another level and that pushed me to make more records like that for the album.

Sounwave: When we first did "King Kunta," the beat was the jazziest thing ever with pretty flutes. Kendrick said he liked it but to "make it nasty." He referenced a DJ Quik record with Mausberg ["Get Nekkid"] and he told me what to do with it. I added different drums to it, simplified it, got Thundercat on the bass, and it was a wrap.

Thundercat: That strong-a** rhythm with banging drums and bass was created by me and Sounwave watching "Fist Of The North Star" while eating Yoshinoya. It's funny because a lot of this album was created eating Yoshinoya and watching cartoons. It was so funky and so black.

Terrace Martin (co-producer): If you dig deeper you hear the lineage of James Brown, Jackie Wilson, Mahalia Jackson, the sounds of Africa, and our people when they started over here. I hear something different every time. I heard Cuban elements in it the other day.

Martin: [For "Complexion"] we were listening to a lot of J Dilla, Jimi Hendrix and Lalah Hathaway, who's on that song too. Robert Glasper played piano over it. Me and Sounwave heard the piano but wanted another beat so we called Lalah Hathaway and got into the spirit of J Dilla. Then Rapsody got to it and murdered it.

Rapsody (featured artist): I was in New York the first time I got the call. [It was] the day after [Lamar's] "Control" verse dropped. Everybody was talking about the verse and Kendrick was in Africa. I went about a year before him so I knew what that trip does to you, especially as a black person.

Lamar: The idea was to make a record that reflected all complexions of black women. There's a separation between the light and the dark skin because it's just in our nature to do so, but we're all black. This concept came from South Africa and I saw all these different colors speaking a beautiful language.

MixedByAli: [Lamar] has an index in his head of everyone's voice and when he hears something that fits, he knows. He sees music as colors. Every song is like putting together a rainbow.

Lamar: Immediately when I heard the beat I heard [Rapsody's] voice and vocal tone. But what made her special was that I knew that she was going to bring the content from a woman's perspective about complexion, being insecure and at the same time having gratitude for your complexion.

Rapsody: He said he wanted to talk about the beauty of black people. I told him to say no more. What tripped me out is Kendrick originally said that he didn't want to do a verse on there. He wanted me to do two verses and Prince to do the hook.

Lamar: That's true. Prince heard the record, loved the record and the concept of the record got us to talking. We got to a point where we were just talking in the studio and the more time that passed we realized we weren't recording anything. We just ran out of time, it's as simple as that.

Thundercat: The album's theme was forming over time and a lot of the social issues he presents on the album were inevitable for him being a black man in America.

Sounwave: I didn't expect ["Alright"] to be the protest song but I did know it was going to do something because the time we're living in made it the perfect song.

Martin: One of the biggest moments was seeing kids marching to "Alright." We cried like babies because we were doing something. This is [our] vessel to get the message out. We had to use art for the message to help heal and help love.

MixedByAli: [The] session [for "U"] was very uncomfortable. [Lamar] wrote it in the booth. The mic was on and I could hear him walking back and forth and having these super angry vocals. Then he'd start recording with the lights off and it was super emotional. I never asked what got into him that day.

Lamar: It was real uncomfortable because I was dealing with my own issues. I was making a transition from the lifestyle that I lived before to the one I have now. When you're onstage rapping and all these people are cheering for you, you actually feel like you're saving lives. But you aren't saving lives back home. It made me question if I am in the right place spreading my voice. "Should I be back home sending this message or be on the road?" It put me in this space where I was in a little bit of a dilemma.

I sat on the beat [for "The Blacker The Berry"] and then the Trayvon Martin and Mike Brown situations happened and I knew that this needed to be addressed.

Sounwave: That last line, "gangbanging make me kill a n***** blacker than me," was a slap in the face. He wants you to be uncomfortable.

Lamar: If you speak on this kind of subject matter you're labeled a conscious rapper. I don't even know [if] that word conscious can only exist in one field of music. Everybody is conscious. That's a gift from God to put it in my heart to continue to talk about this because that's how I'm feeling at the moment. The message is bigger than the artist.

When Tupac was here and I saw him as a 9-year-old, I think that was the birth of what I'm doing today. From the moment that he passed I knew the things he was saying would eventually be carried on through someone else. But I was too young to know that I would be the one doing it.

With over a decade of experience as a journalist and editor, Andreas Hale has been called the "Swiss Army Knife of Journalism" by his peers. His work has been featured on Billboard, MTV, Complex, Jay Z's Life+Times, XXL, and The Source, among others. He is also the co-host of combat sports podcast "The Corner" on the Loud Speakers Network.

Tune in to the 58th Annual GRAMMY Awards live from Staples Center in Los Angeles on Monday, Feb. 15 at 8 p.m. ET/5 p.m. PT on CBS.