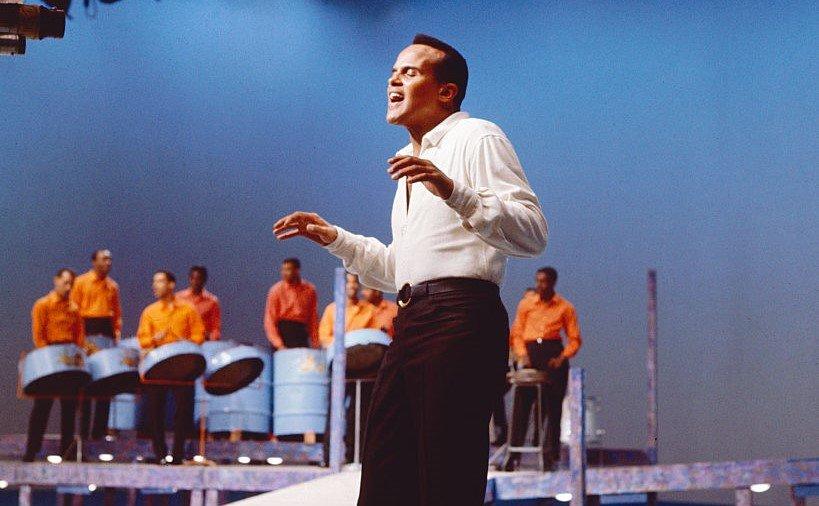

Photo: Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

feature

Remembering Harry Belafonte’s Monumental Legacy: A Life In Music, A Passion For Activism

American icon Harry Belafonte passed away on April 25 at age 96. Throughout his legendary musical and acting career, Belafonte broke barriers and demonstrated a commendable commitment to equality.

An American icon whose outsize influence spanned generations and blazed trails, Harry Belafonte’s death at the age of 96 marks the end of a legendary life and career that shone in not only music, but social issues and the culture at large.

A two-time GRAMMY winner and 11-time career nominee, Belafonte's impact on the Recording Academy has lasted as long as the organization itself. The artist earned a nomination at the first-ever GRAMMY Awards in 1959 for Best Rhythm & Blues Performance (for his album Belafonte Sings the Blues). He’d win three years later for Best Performance- Folk for "Swing Dat Hammer." His other win came in the form of a GRAMMY for Best Folk Recording for An Evening With Belafonte/Makeba. He received a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2000, and three of his recordings are in the GRAMMY Hall of Fame.

"Harry Belafonte has made an immeasurable impact on the music community, our country and our world,” says Harvey Mason jr., CEO of the Recording Academy. "Through his music and his activism in the civil rights movement, Belafonte has used his voice to break racial barriers in America since the ‘50s. It’s been an honor to celebrate his influence on our society throughout his impactful career."

Over nearly a century of life, Belafonte left a significant impact that has resonated with common audiences and up to the highest echelons of arts and politics. As news of his passing spread across the world, remembrances, praise and thanks appeared on social media.

Quincy Jones, one of many luminaries celebrating Belafonte's legacy today, remembered, "From our time coming up, struggling to make it in New York in the '50s with our brother Sidney Poitier, to our work on 'We Are The World' & everything in between, you were the standard bearer for what it meant to be an artist and activist."

"He inspired me so much personally," said John Legend, recalling Belafonte’s immense impact. "I learned at his feet basically about all of the great work he’s done over the years, and if you think about what it means to be an artist and an activist he was literally the epitome of what that was." Former President Barack Obama heralded Belafonte as a "barrier-breaking legend" who transformed "the arts while also standing up for civil rights. And he did it all with his signature smile and style."

A Trailblazing Artist Who Never Simply Toed The Line

In a 1998 "American Masters" interview for PBS, Belafonte mused about his life and legacy, noting, "One way or another, the essence of life is, in fact, the journey itself."

If that’s the case, Belafonte’s momentous path from his humble Harlem, New York youth to a successful club act, singing star and champion of equality amounts to an astonishing rise that no other Black artist had ever experienced before. His velvety voice and penchant for singing earworm songs along with a relaxed style endeared him to his initial '50s-era audiences.

Yet Belafonte was no mere one-note easy-listening act; he helped popularize calypso, was essential in bringing folk music to the mainstream, and also successfully recorded blues and even novelty songs. Sometimes his music was bombastic ("Jump in the Line (Shake, Señora)"), while on other occasions deftly understated ("A Hole in the Bucket"). Early hit "Matilda" begins with Belafonte happily whistling. "Hey! Ma-Til-Da," he cooly croons.

Influenced by his nightclub act, Belafonte's 1956 album Calypso was the first LP to sell one million copies — a stunning achievement for a genre not widely heard before. (As a result, the Library of Congress later added it to the National Recording Registry of significant American work.) Calypso was marketed as "not just another presentation of island songs," and its liner notes can be read as a reflection of the often complex role race and fame played in Belafonte's life.

Calypso's "songs [are] ranging in mood from brassy gaiety to wistful sadness, from tender love to heroic largeness," its liner notes read at the time, helping sell a fresh genre to a new audience. "And through it all runs the irrepressible rhythms of a people who have not lost the ability to laugh at themselves."

Throughout his career, Belafonte deftly navigated the line between mainstream hits and songs with a deeper meaning. When it came to recording "The Banana Boat Song" — the instantly recognizable sing-along party tune from Calypso, which originated as a traditional Jamaican folk song — Belafonte told "American Masters" that the song was a "conscious choice." Singing its memorable "Day-o!" refrain was "beautiful, powerful" and "a classic work song that spoke about struggles of the people who were underpaid and the victims of colonialism. In the song, it talked about our aspirations for a better way of life."

Aside from his singing career, Belafonte also dominated Broadway. In 1954, he won a Tony Award for his role in "John Murray Anderson’s Almanac," a musical revue. He also dabbled in film, from his 1953 debut to Spike Lee’s 2018 movie BlacKkKlansman.

He remained humble, if not slightly casual, about his success. "I had no problem being thrust into the world of stardom because I never thought about it," Belafonte told ABC News in 1981. "Nowhere in my boyhood dreams was I thinking one day I’d be in Hollywood, one day I’d be on Broadway, one day I’d be making an album that was successful. I was quite content, as most Blacks were in that period, to practice my artform and hopefully find a constituency somewhere in the world because the larger dream eluded all of us."

A Lifetime Of Activism

As his fame grew, Belafonte’s penchant for activism collided with a fast-changing America that was confronting the oppression of the '50s and reacting to the turbulence of the '60s. As a result, Belafonte's impressive musical legacy will forever be intertwined with his passion for activism.

Belafonte rubbed shoulders with the titans of his time: He attended John F. Kennedy’s inaugural gala (an invitation extended by Frank Sinatra), received inspiration from artist and activist Paul Robeson, he became a face of the civil rights movement alongside close friend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

In fact, it was Dr. King who initiated the meeting with Belafonte. "He was coming to New York to speak to the religious community, the ecumenical community at the Abyssinian Baptist Church," Belafonte recalled to "PBS Newshour" in 2018 of their first encounter. "As a young Black artist on the rise [at the time], I began to make a bit of noise on my own terms. I began to violate the codes of racial separation. I understood the evils of racism and rebelled from my youth. He was 24. I was 26."

That confab began a friendship that would help shape the civil rights movement at large. Belafonte participated in the Freedom Rides and March on Washington, and even hosted "The Tonight Show" for a week in 1968 where Dr. King was one of his guests. The singer took King’s assassination as an exhortation, and committed fully to the quest for equity; he remained a passionate activist for decades.

Musically, that passion included an urge to help the plight of people in war-stricken Africa; his idea for a benefit single resulted in "We Are the World." The smash swept the GRAMMYs in 1986, winning Record Of The Year, Song Of The Year, Best Pop Performance By A Duo Or Group With Vocal and Best Music Video, Short Form. In recent years he founded the social justice organization Sankofa, released the book My Song: A Memoir and was the subject of the documentary Sing Your Song. Last year he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

"(He was a) shining example of how to use your platform to make change in the world," said Questlove on Instagram. "If there is one lesson we can learn from him it is, ‘What can I do to help mankind?’"

He added, "Thank you Harry Belafonte!"

Photo: Sam Emerson

feature

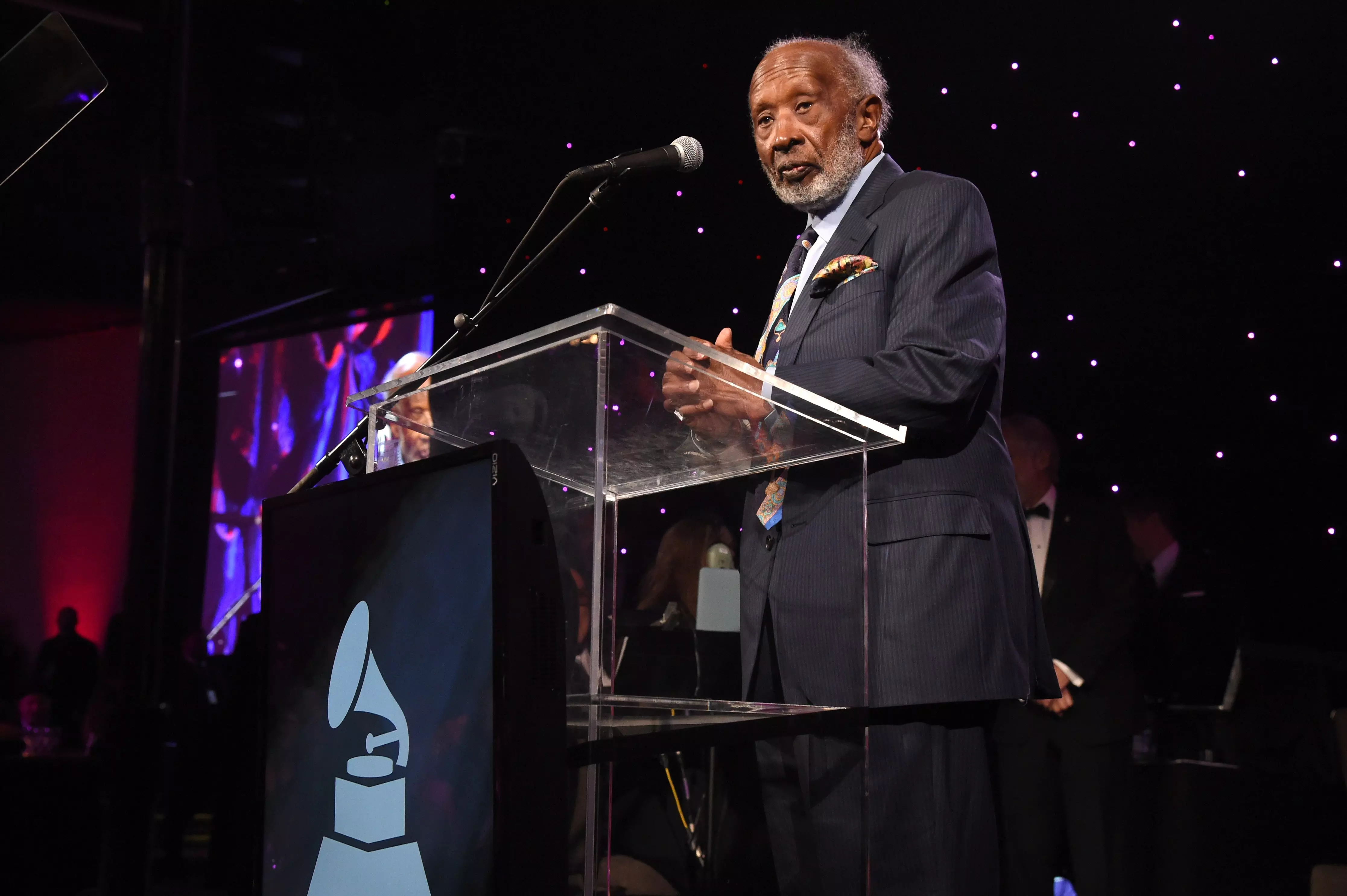

Remembering Quincy Jones: Musical Pioneer, Inspiration, Activist & Renaissance Man

The conductor, composer, producer, arranger, musician, activist, and all-around mastermind passed away on Nov. 3 at age 91. An icon, Jones worked with most of music’s legendary names and inspired countless others, creating an unmatched legacy.

Quincy Jones helped shape nearly every facet of pop music history, either directly or indirectly, for more than half a century. On Nov. 3, the consummate multi-hyphenate passed away at the age of 91.

The recipient of 28 GRAMMY wins and 80 nominations — ranking third and fourth most in the organization’s history, respectively — Jones will be remembered for his work with everyone from Michael Jackson to Frank Sinatra, Aretha Franklin to Count Basie. He was also known for his powerful support of many humanitarian causes.

Jones’ legacy within the Recording Academy dates back to just a few years after its founding. The Great Wide World of Quincy Jones was nominated for Best Jazz Performance Large Group at the 3rd GRAMMY Awards, and not a decade passed since without the icon receiving an award. In addition, Jones was the recipient of the Trustees Award in 1989, the GRAMMY Legend Award in 1992, and the MusiCares Person Of The Year in 1996, and was the subject of a GRAMMY Foundation gala tribute in 2014. In 2023, Jones became the first-ever recipient of the Academy & State Department’s PEACE Through Music Award.

In presenting that last award, Recording Academy CEO Harvey Mason jr. called Jones his "friend and mentor," and noted that his respect and admiration for Jones are echoed throughout the organization. "We are all absolutely heartbroken by the passing of the incomparable Quincy Jones," Mason jr. said in a statement. "A master of many crafts, Quincy’s artistry and humanity impacted artists, music creators, and audiences around the world and will continue to do so. He has been recognized by his Recording Academy peers with an extraordinary 28 GRAMMY awards, standing among the most celebrated recipients in GRAMMY history. Quincy leaves behind an unmatched legacy and will always be remembered for the joy he and his music brought to the world."

Jones' long list of accolades also includes honorary degrees from Harvard, Princeton, and Juilliard, as well as a National Medal of Arts. His legacy doesn’t stop with the immense impact of his music, but extends to activism and humanitarianism. Jones was an advocate for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his Operation Breadbasket, served on the board of People United to Save Humanity, founded the Quincy Jones Listen Up Foundation, supported the work of the NAACP, GLAAD, and other organizations, and produced the "We Are the World" charity single.

With such a massive footprint both personally and professionally, it should be no surprise that news of his passing has resulted in seemingly endless remembrance and thanks across social media. Elton John, Victoria Monét, Reverend Al Sharpton, LL Cool J and Lin Manuel-Miranda were among the many artists praising Quincy Jones' influence and legacy.

"Wow, Q - what a great ride!!" Lionel Richie wrote on X, accompanied by a picture of the two together. Jones and Richie worked closely together on "We Are the World," a project which was also co-written by Michael Jackson. After connecting with Jackson for The Wiz, Jones became a frequent collaborator of the pop icon, including the albums Off the Wall, Thriller, and Bad.

"The world mourns the loss & celebrates the life of Quincy Jones," the Jackson estate shared. "A legendary talent whose contributions to music spanned generations and genres. What an MJ/Q decade-long partnership produced is unmatched and includes the biggest selling album of all time. Rest in Peace, Q."

Clive Davis similarly mourned Jones’ passing. "Quincy Jones was a true giant of music," he wrote on Instagram. "Whether it was jazz, pop, r&b or rock, no genre of music escaped his genius…Say ‘We Are the World’ and say ‘The Color Purple’ and you’ll understand the range of his music. He was the ultimate music renaissance man and a true inspiration to all of us in music."

In an Instagram post, John Legend reflected on joy Jones "brought to every room. He was the life of the party, so charming and full of light. I feel so fortunate to have witnessed it in person. But we’re all so fortunate to live in a world made more beautiful by the music he created."

A True Innovator Who Always Built Up

"I'm often asked what my 'formula for success' is...but to be honest, there is no formula or road map, and if anyone tells you there is, they're full of it," Jones wrote in the introduction to his 2022 book, 12 Notes: On Life and Creativity.

For Jones, that winding road started with a childhood on the South Side of Chicago, before moving in his early years between Kentucky and Washington before joining his school band and choir, not to mention convincing Count Basie trumpeter Clark Terry to give him lessons. He also crossed paths and shared the stage with Ray Charles, when Jones was 14 and Charles 16. An obviously prodigious talent, Jones relocated to New York by his early 20s; he quickly became a freelance arranger for Count Basie and musical director, arranger, and trumpeter for Dizzy Gilespie.

Jones began his solo recording career in 1956 with This Is How I Feel About Jazz, and moved to Paris, where he learned to arrange strings and studied music theory. This was followed by invitations to work on stage musicals and film soundtracks (including The Pawnbroker, In the Heat of the Night, and In Cold Blood (not to mention much later contributing music to and even appearing in the Austin Powers series. Jones had signed as an artist to Mercury Records in 1958 and moved his way up the executive ladder — a first for a Black man at a major label — becoming music director and, eventually, vice president.

After excelling in jazz at Mercury, Jones reached pop success by shepherding Lesley Gore's "It's My Party" to the top of the charts. He continued releasing his own material as well, experimenting at the intersections of jazz, funk, and more.

While Jones may be most known for his 1980s run with Michael Jackson, the decade also saw him open Qwest, a label that released works from the likes of Frank Sinatra, Lena Horne, and New Order, among many others. "It’s so sad to hear about Quincy Jones. When he signed us to his label, he made us feel so welcome - inviting us to dinner at his home every time we were in town," former New Order bassist Peter Hook posted on X. "He made us big in America. He was so humble & sweet that you immediately fell in love with him."

Read more: Mogul Moment: How Quincy Jones Became An Architect Of Black Music

Jones won 13 of his 28 GRAMMYs in the ‘80s, including Record Of The Year, Best Pop Duo or Group Performance, and Best Music Video for "We Are the World." In a recent interview with GRAMMY.com, Lionel Richie described Jones’ steady, nurturing hand on the project: "I asked Quincy a very important question one time. I said, ‘How in the world did you deal with all of those various personalities and stuff?’ He said, ‘What do you think an arranger does? … My job is to organize chaos.’"

A Jack Of All Trades — And Master Of All

In addition to writing and recording his own music and producing for others, Jones proved to be a mastermind across many other parts of the entertainment industry. In the '90s, he launched Quincy Jones Entertainment. Beyond operating his record label, the company produced successful TV shows like "The Fresh Prince of Bel Air" and "Mad TV", and helped publish music magazines Vibe and Spin.

The ‘90s also saw Jones’ music intertwined with hip-hop, most notably as sampled by Tupac in the chart-topping "How Do U Want It." The legendary Ice-T, who had guested on Jones’ album Back on the Block, expressed the impact that the legendary musician and producer had made: "Love you Quincy.. You changed my life."

One of Jones’ final appearances on record came in 2022, where he provided a spoken word track to The Weeknd's Dawn FM called "A Tale By Quincy." The Weeknd’s Abel Tesfaye even wrote the foreword to Jones’ 2022 book, 12 Notes, which included a powerful summary of the impact that Jones had on Tesfaye — and the entire musical world. "Even if you've already read his autobiography or know everything there is to know about him, I hope you'll take time to listen to the advice he has to share with you in the pages of this book," Tesfaye wrote. "Because I promise it is what matters the most."

"My fans know how important Quincy was to the fabric of my music," he added on X. "[I] tried to capture what he meant to me as a human. Let’s celebrate his life today."

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Khatia Buniatishvili Plays "Mephisto-Waltz No.1"

Peanut Butter Wolf Talks New Campus Christy Album & What's Next For Stones Throw

Warner Music Group's Paul Robinson To Be Honored With 2025 Entertainment Law Initiative Service Award

Your Vote, Your Voice: 6 Reasons Why Your GRAMMY Vote Matters

JOHNNYSWIM Reveal The Mic That Defines Their Sound

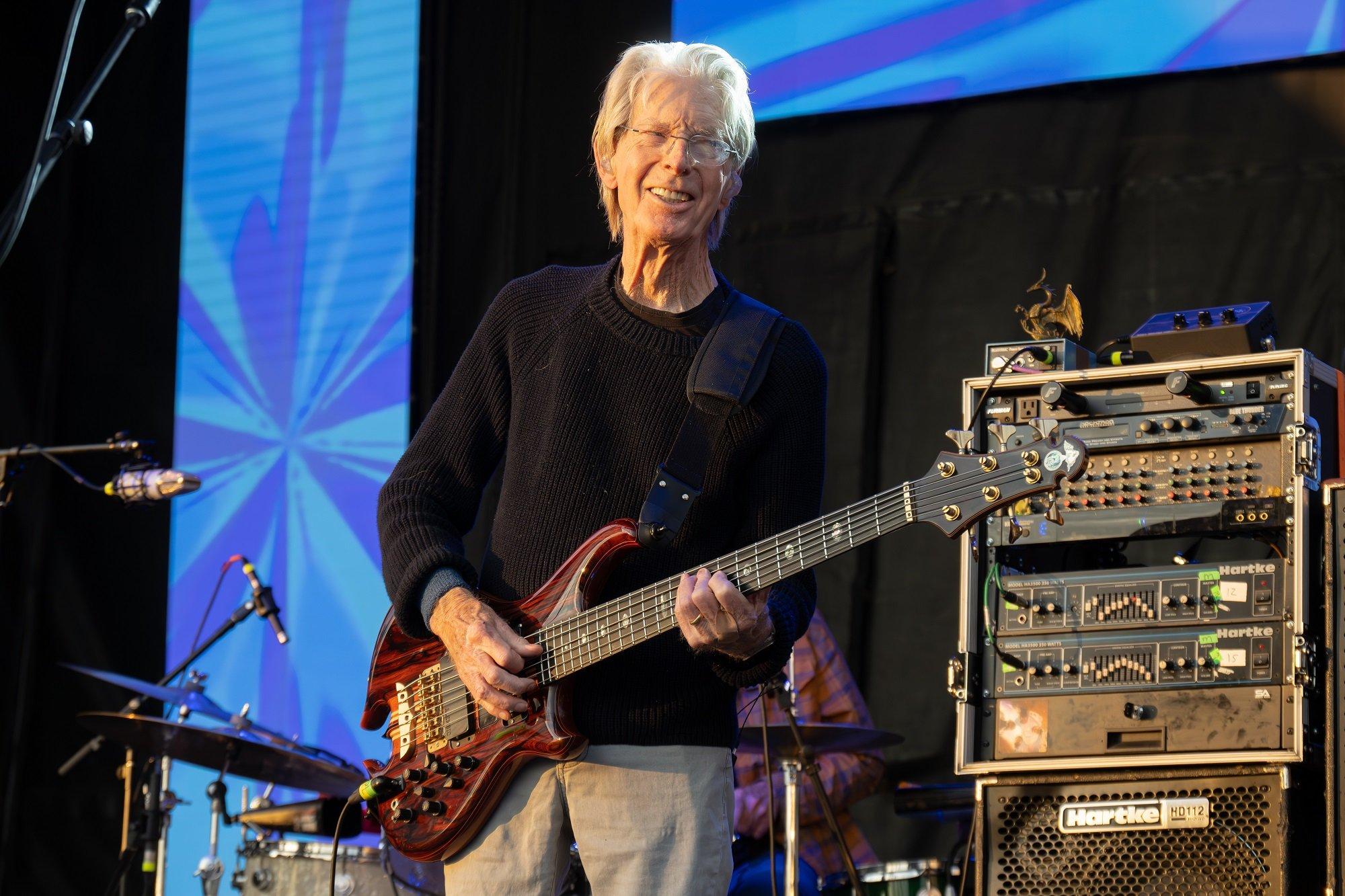

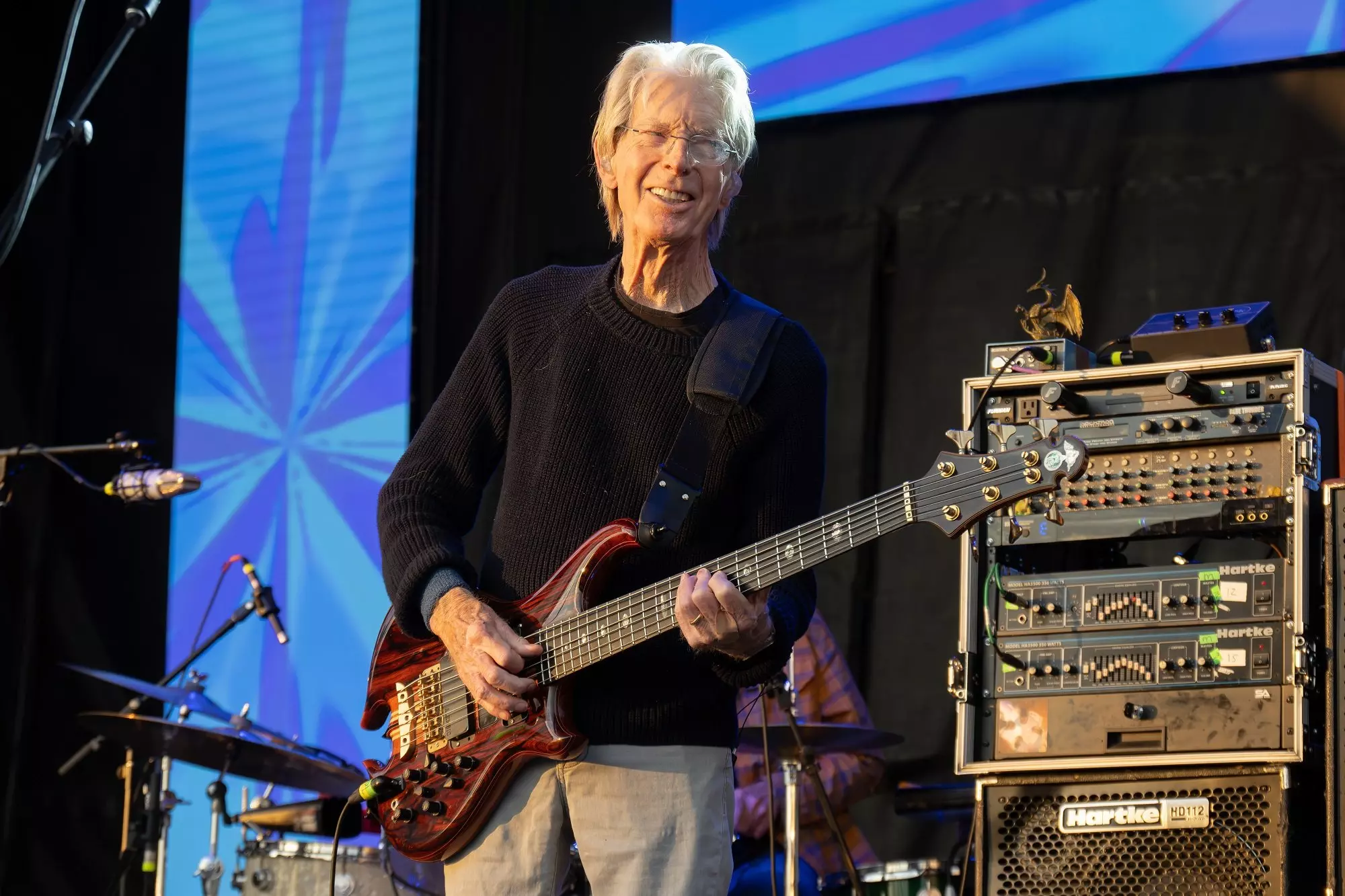

Photo: Astrida Valigorsky/Getty Images

news

Remembering Phil Lesh, Grateful Dead Co-Founder And Bassist With An Unbreakable Chain

The legendary bassist and his bandmates in the Grateful Dead will be honored as 2025 MusiCares Persons Of The Year during a GRAMMY Week event on Jan. 31 in Los Angeles.

And then there were two. Phil Lesh, co-founder and innovative bassist for the Grateful Dead, passed away peacefully on Oct. 25 at his California home surrounded by family. He was 84.

With Lesh’s death, Bob Weir and Bill Kreutzmann are the only remaining original members of the psychedelic rock band that formed in Palo Alto in 1965. Earlier this week, it was announced that the Grateful Dead had been named the 2025 MusiCares Persons Of The Year.

Lesh’s death was announced late in the day on Friday on his official Instagram. Margo Price, one of the first to comment on the news, simply said, "Thanks for the music." Just this past March, Lesh was joined on stage at The Capitol Theatre by friends and fellow artists to celebrate his 84th birthday. On Friday night on X, the New York venue said they already missed the musician "more than words can tell."

"The Recording Academy mourns the loss of Phil Lesh," Recording Academy CEO Harvey Mason, jr said in a statement."For their outstanding contributions to the recording industry, he and his fellow Grateful Dead members were honored in 2007 with our Recording Academy Lifetime Achievement Award. Phil’s legacy is timeless and will live on for generations to come and we look forward to honoring him and the Grateful Dead at our MusiCares Person of the Year ceremony in January."

Phil Lesh left a lifetime's worth of music to be grateful for. The musician was born in Berkeley, California on March 15, 1940. He played trumpet and violin in high school and, during these formative years, fell in love with free jazz and experimental music. This penchant for improvisation that became his trademark for three decades as a member of the Grateful Dead — a band of musical brothers that left a lasting legacy on the world.

Lesh became a bassist by default. He was working a variety of jobs, including driving a mail truck and working at a radio station, when Jerry Garcia convinced him to join the new rock band he was forming (the Warlocks), who quickly morphed into the Grateful Dead.

The Dead defined an era. The band represented a subculture that influenced the mainstream for decades from lifestyle to fashion; from music to marketing. And Lesh, as a co-founder of these musical misfits, was a key cog in this long and strange trip.

"Phil Lesh changed my life," Dead drummer Mickey Hart wrote on X. "Phil was bigger than life, at the very center of the band and my ears, filling my brain with waves of bass…. Phil was a master of a style he invented, he was singular, an original, nobody sounded like him, nobody."

Read more: A Beginner’s Guide To The Grateful Dead: 5 Ways To Get Into The Legendary Jam Band

The bass does not often get the glory, but it is the backbone of many groups; it provides that steady beat and rhythm that guides the rest of the band. Sometimes, the bass lines are simple; other times complex. Lesh's dexterity with the instrument allowed him to wield it as an inspirational source and force — especially live — as a conduit to take the Grateful Dead and their fans to new realms.

Lesh played bass like it was the lead instrument of the band. Listen to the Grateful Dead’s vast catalog and the groove of his funky bass notes and improvisations often trump Garcia’s lead guitar playing. Rolling Stone cited Lesh as one of the "50 Greatest Bassists of All Time," noting that that "In the same way that the Grateful Dead reconfigured how a rock band should sound — looser and jammier, incorporating equal parts jazz and country — Phil Lesh made us hear the bass in a new way."

The Grateful Dead were innovators. No two shows were ever the same. The spirit of each night was unique and that spirit was fuelled by the band members (and just as often by the various drugs that they were under the influence of) and where they went on these spacey jams and explorations, Lesh was often the guide.

In 1994, Lesh and his jamband mates were enshrined into the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame when Bruce Hornsby officially inducted the Grateful Dead. In his acceptance speech, Lesh thanked Deadheads worldwide, acknowledging that "without them, we wouldn’t be anywhere, much less right here, right now."

After Garcia passed away in 1995, Lesh and Weir both continued to play and perform, together and separately, but never again under the Grateful Dead moniker. Lesh founded Phil Lesh & Friends and, in later years, played often with his sons: Grahame and Brian; Weir fronted Dead and Company, who this past summer completed a 30-day residency dubbed Dead Forever in Las Vegas at the Sphere.

On X, as news of the musician’s passing spread, tributes poured in from celebrities, fellow musicians, legendary venues, and regular Deadheads. The Empire State Building even announced it would light up the New York City skyline for one hour on Friday night in homage to Lesh’ legacy.

Beyond its longtime care for its community of loyal fans (Deadheads), the band supported many causes over the years — from mental health to music education and social justice. In 1997, Lesh and his wife Jill founded the Unbroken Chain Foundation to raise money and give back to various charitable organizations.

MusiCares also mourned the loss of Lesh. "As a legendary bassist and founding member of the Grateful Dead, Phil’s distinctive contributions to music, advocacy, and philanthropy leave an enduring impact," the organization said in a statement. "Phil will be reverently honored with his Grateful Dead bandmates as our 2025 Persons of the Year, commemorating their journey that transcends music and fosters a profound sense of unity and generosity. This tribute stands as a testament to Phil’s remarkable legacy, commitment to creating community, and unwavering dedication to causes close to his heart, including his Unbroken Chain Foundation and MusiCares."

Phil Lesh leaves behind his wife Jill and children, Grahame and Brian.

In memory of Phil Lesh, press play on five songs that feature bass lines that groove, melodies that linger long after the record is done, and showcase his musical legacy and influence.

"Box Of Rain"

This country-folk song is a Deadhead favorite and concert staple. The melody and instrumentation for "Box of Rain" (from American Beauty,1970), came to Lesh as something to sing to his dad, who, at the time of its writing, was dying of cancer; Lesh practiced it in his head during his drives to visit his ailing father at his nursing home.

"Truckin'"

One of the Dead’s most mainstream cuts and highest-charting songs, it’s hard to listen to this catchy number without getting hypnotized by the funky bass groove supplied by Lesh that keeps the song rollicking down the highway on this long strange trip.

"Cumberland Blues"

From 1970's Workingman’s Dead, this song is about the trials and tribulations of toiling in the Cumberland coal mines in Kentucky. In live shows, this is one where Lesh was let off his leash; listening to this track you can feel how much fun the bassist is having.

"St. Stephen"

This song was co-written by Jerry Garcia, Phil Lesh and Robert Hunter. Appearing on the 1969 album Aoxomoxoa, this tune opens with Lesh playing single notes that resonate and then kicks into a romp that continues to build until the bridge that slows things down briefly before another explosion of sound that spirals the song to a climactic ending with the melodic bass lines of Lesh leading this psychedelic trip.

"Unbroken Chain"

Lesh co-wrote this complex melodic song, which is also the name of his charitable foundation, with longtime Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter. Appearing on 1974’s From the Mars Hotel, the band never performed the song in concert until 1995, likely due to its difficulty.

The phrase symbolizes (just like the classic 1907 gospel hymn "Will the Circle be Unbroken" the journey of the band and the fans that have followed them on their trips for nearly 60 years. Though yet one more member of the Grateful Dead is now gone, the songs remain to help family, friends and Deadheads grieve to make sure the links to their music never breaks or fades away.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Khatia Buniatishvili Plays "Mephisto-Waltz No.1"

Peanut Butter Wolf Talks New Campus Christy Album & What's Next For Stones Throw

Warner Music Group's Paul Robinson To Be Honored With 2025 Entertainment Law Initiative Service Award

Your Vote, Your Voice: 6 Reasons Why Your GRAMMY Vote Matters

JOHNNYSWIM Reveal The Mic That Defines Their Sound

Photo: Corine Solberg/Getty Images

interview

Living Legends: Lionel Richie On 'The Greatest Night In Pop,' "American Idol" & The Evolving Essence Of The Music Industry

"When I wrote those lyrics…it was exactly the feeling of where we are now as a world," Lionel Richie says of "We Are the World." In a wide-ranging interview, the four-time GRAMMY winner discusses the iconic charity single and his career to date.

Whether explaining to his parents that the Commodores would be the "Black Beatles" or writing a mega-smash charity single in a single evening, a young Lionel Richie has something of a mantra: "Everything was possible."

When the now-iconic "We Are the World" first hit the airwaves in 1985, listeners surely were awed at the thought of so many legends in one room. Performing under the banner of USA for Africa, the track featured everyone from Ray Charles to Stevie Wonder, Michael Jackson to Bruce Springsteen, Cyndi Lauper to Tina Turner, and sold more than 20 million physical copies to raise money for African famine relief. The song’s recording was documented and encapsulated in the recently released documentary The Greatest Night in Pop.

Richie is the glowing supernova of musicianship creative wrangling at the core of the song and film. "Part of the whole magic of the song was to know the back side of it," Richie tells GRAMMY.com, hinting at the open, warm tone that has characterized his entire career.

Richie's sterling vocals and immaculate songwriting first rose to international prominence in his time as co-lead singer of Motown heroes the Commodores, for whom he wrote songs like "Easy" and "Three Times a Lady." Richie expanded his already endless pop charm as a solo artist, topping charts and winning countless acclaim and listeners’ hearts alike with songs such as "All Night Long (All Night)," "Hello," "Say You, Say Me," and "Dancing on the Ceiling."

When the concept for creating a track to raise funds and awareness for African famine relief was first broached by legendary artist and activist Harry Belafonte and manager Ken Kragen, Richie was tapped to write the song with Michael Jackson. The duo pulled an all-nighter to write the track a day before the first recording session — which also happened to be the very same day Richie was to host the American Music Awards, his first hosting gig on television. (Richie has become a fixture on TV, including his recent stint as a judge on "American Idol.")

Throughout his myriad roles and projects, Lionel Richie remains both incredibly professional and one of the warmest personalities in the music industry — not to mention a captivatingly brilliant musician and four-time GRAMMY winner. GRAMMY.com caught up with Richie to discuss the making of "We Are the World," finding himself in the room with every one of the icons he admired, and the continued need for hope and positivity 40 years later.

I have to tell you, I re-watched The Greatest Night in Pop this morning, and it is no less incredible after another watch.

Thank you. It's one of those moments in time. Just to see the positivity, number one, and number two, the impossibility of how we pull this off. Trying to do that today, you would just want to drive yourself crazy. There's no way today you can keep a secret.

Of course you’d have a leak, and is everybody going to show up? There’d be too many egos. "Leave your ego at the door?" You won't even leave your ego at the phone call.

The whole business has changed. But in the documentary, you really feel the weight of the challenge and the massive scope of opportunity. During that time, were you completely confident or or was there a constant worry that it might fall apart? Perhaps you had so many responsibilities that success and failure didn't even cross your mind.

You know what's so brilliant about being young and naïve? Everything has possibilities.

I look back on my career, when I walked in that door that fateful day that I was going to tell my parents that I was going to drop out of my last semester of my senior year and go full time with the Commodores. And I said, "Mom, Dad, we're the Black Beatles. We're going to take over the world." That takes a lot of just innocence and naivety and youth. Everything was possible. With "We Are the World," we were all kind of sitting there going, "What can we do [to make this work]?" And as we started calling up people, it just became "I'm in." "I'm in." "I'm in."

Of course, Ken [Kragen, manager] didn't tell us that he was making all these phone calls. We just thought it was going to be Quincy [Jones], Stevie [Wonder], Michael [Jackson], and myself. And Harry Belafonte. And the next thing we know, we've got all these artists waiting for the song that we haven't written. [Laughs.]

I think that was so wonderful that you didn't have that level of project in mind. Whilst naivety is part of the process, I feel like if you weren't able to be so in the moment, the song may have come out differently.

I always believe that if you have too much time to think about something, you're going to mess it up. I said yes to something that I didn't realize I had no time to do. This is my solo time in life. I've just left the Commodores; I'm hosting the American Music Awards. I've never done that before.

And of course, the pressure was there as well. Who is this kid to host this show alone? Alone, alone, not with two or three hosts. There was a lot of doubt as to whether this kid could do this or not, you know. As time went on, it just became another part of the story. And I've always believed I'm very good at getting myself into crap. And then I have to work my way out of it.

You're a good swimmer.

[Laughs.] Yeah. And so this thing just started evolving. "Okay, Lionel, what about the rehearsal for the American Music Awards?" And I go, "Oh, that's right. We have to rehearse."

The rehearsal time was also the time we had to cut the track for "We Are the World." And then we have to write the lyrics. Meanwhile, I have to rehearse [for the AMAs]. But, you know, I look back on it, honestly, and it was just divinely guided. Sometimes if you just have a chance to sit back and think about the intricate parts of it, everyone showed up at the right time to do the right thing.

It was astonishing to think about how many roles you had in that record coming to life. You were a writer, a singer, a producer, a coach, a psychiatrist, a guide. And you continue taking on so many different types of projects and roles to this day.

Well, let me tell you what makes things like "We Are the World" happen. I won’t just sit here and talk about, you know, how I did it. That was a room full of pros, you follow me? Quincy Jones, master producer, master arranger. I asked Quincy a very important question one time. I said, "How in the world did you deal with all of those various personalities and stuff?" He said, "What do you think an arranger does?" I said, "What do you mean?" He said, "What do you think I do for a living? My job is to organize chaos." In other words, the woodwinds are playing one thing. The brass are playing something else. The violins are playing something else. And all together it sounds like a song. Well, he was the master of that.

When you bring in artists from all different genres, each one of those artists, A, had their own sound, and B, knew how to deliver it. So all we had to do was kind of set the stage for them to do that half a line and pull it off. But behind the scenes, look at Humberto Gatica. He is a great engineer. How many tracks can you mess up? He had 99 million tracks and all of a sudden we couldn't have a delay [in the schedule]. There was no delay possible. I think what made my part of this whole thing, I was just putting out fires. Wherever there was a fire, like, "Okay, Bob Dylan, you need to go see Stevie Wonder. [Laughs.] And Huey Lewis, you just need to calm down." He thought he was just going to come and hang out.

Oh, Huey is such a fun guy!

Huey was going, "I'm going to sing whose part?" [Laughs.] It made everybody honest. I said, "Okay, Quincy, how are we going to pull this off? Is everybody going to go in the vocal booth one by one to do their parts?" He said, "No, no, no, no. We're going to put them in a circle and let them sing to each other." And I said, "What?"

He said, "I promise you, they'll be perfect on every round." Because when you're facing each other, there is no "Give me another take" or "Give me two more takes" or "Let me warm up." Just the fear factor of facing every artist you've ever admired in your whole life. There's Ray Charles over there. There's Kenny Rogers over here. There’s Diana Ross.

And Tina Turner!

And Bruce. And Billy Joel. We were, basically, the youngsters in the room. There's Michael. We'd all been around in the business a long time, but we'd never just been in a room to face each other.

So I think what was so amazing is when we went around one time at that piano, just to hear how it was all going to sound, that's when we knew we've got something. It was going to be a good sound.

Fitting all those different sounds and voices is such a beautiful achievement. It really makes you stand out, that ability to guide people and projects so naturally. It really makes sense that you have this continued role as a statesman of the industry, even down to your work on "American Idol."

You know what was so great? What we all heard back then, and what still rings true today, there's a word that the world needs right now. It's called hope. [When] that song came out 40 years ago; it was this amazing light, this beacon of hope. People started going, "Ah, okay, you're right. We need to care about each other."

It's one of those aha moments when you realize that a group of us got together and actually made that statement. As world-famous artists, we took all of our light as celebrities and entertainers and songwriters and shined it on hunger and starvation in the world. It was just a great statement.

I’m sure you have countless admirers who come up to you and talk about your work, but can you share some things that listeners have told you about that song in particular?

What I loved is when you start getting the 7- to 12-year-olds [saying] "We sing ‘We Are the World’ in our school!" Then that segues over to "American Idol."

When I first met Bao [Nguyen], the director [of The Greatest Night in Pop], he scared me to absolute death because I'm thinking that we're going to bring in a well-seasoned director from 1983 or 1984. He says, "I was two years old when that song came out in Vietnam." [Laughs.]

A lot of people just heard the song, but they didn't know the background [or my role in it]. So they didn't know that Michael and I wrote the song together. They knew I was maybe in the song, but they didn't know to what degree. I’m having a lot of people just come up to me with the sheer discovery. "Oh, my God, I didn't even know you did it."

"Where have you been?"

It really tells how blessed we were, because think about this now. All of us [working on the song] went on to have careers, major careers; that was the beginning of our big explosion.

What I love the most, I think, is just the fact that what Michael and I set out to do with that song was we wanted not a song, not a hit record. We wanted an anthem. We wanted a song that will stay around generation after generation, year after year. When people ask me right now, "God, Lionel, you need to write another song, because we need it so much today." And I go, "Play the song again."

It's so relevant. Absolutely.

Everything I wanted to say 40 years ago, I would write today. In other words, history just keeps repeating itself over and over again. And everyone keeps thinking you need something new. No, the whole song said everything.

But then when was your last all-nighter? Because that was a pretty epic all-nighter that you had that night.

[Laughs.] That was an "all-two-dayer"! That was the day before rehearsing for the American Music Awards. You then wake up and then actually start rehearsing from 7 in the morning at the Shrine Auditorium 'til the show started, and then to leave there at 11 o'clock at night, 12 o'clock at night. I forgot to also mention [that] I was not quite prepared for hosting, because this was my first time doing it. But also, I wasn't ready to win. [Editor's note: Richie won six times at the AMAs the year, including Favorite Pop/Rock Male Artist.]

It was a lot of moving parts. But the beautiful part about it was, I think the dedication and the hearts of each of those artists. Everybody came to shine their light on this issue. And the brilliance of it is, it worked.

What's something positive that you've been feeling about music lately?

Well, here's what's happening. I went into "American Idol" thinking, There is no possible next level of artistry. Because I've been there, done it, I've seen it. This is my eighth year coming up on "American Idol" and talent keeps showing up. Unique talent keeps showing up. Writers keep showing up. And I think what I'm looking forward to is when the industry can now keep up with the talent. Because we're overflowing with talent.

The problem now is, how do we get all of this talent recognized around the world? I mean, when I get to the top 20 on "American Idol" literally, I could start a record company on the top 20. We're throwing off such amazing talent. You constantly have to think, Okay, what are we doing?

For example, Jennifer Hudson did "American Idol," and she was let go at number nine, and then went on to become a massive star. This year coming up, Carrie Underwood won "American Idol" and here she is now coming back as a judge and mentor.

My situation now is, how do we get more of this talent recognized to the world? We were very fortunate back then because everything back then was global. There were only basically four different networks you could deal with. And then if you want to go outside of that, it's called BBC. What the internet did was great in terms of everybody's on it, but it also made it a big soup. You've got so many different angles and avenues. How do you focus your audience?

I think what's going to happen in the next couple of years is technology is going to be able to help us in a lot of ways. Because there has to be a new model that's going to be able to showcase not only the artists, but then there's the writers, the producers, the engineers, the musicians.

Yes! More focus on the collective who create the art. Where are the credits? I want my liner notes.

Exactly! I don't want to be the guy who’s like, "Bring back the good old days," but…

I think a lot of people are saying the same thing, no matter what age they are.

I couldn't wait to read the liner notes. Who's on that record? Oh my God, that writer was on there. Oh my God, that musician was on there. So-and-so sat in on the session. Part of the whole magic of the song was to know the back side of it, what was really happening. There's a lot that we can discover going forward, but there's a lot that we are losing from the past that I would like to bring up. Because we're not really giving credit where credit is due.

We need time. But we also need the advocate, the voice behind a message, which you are so clearly great at. You saw darkness in the world and put out a song. We know that song is not going to fix whatever the problem is, but the music becomes a comfort. What is that song for you that brings you to the place where you're feeling downright comfort?

I don't want to be the one to go that route, but my go-to for calm is "Easy Like Sunday Morning" ["Easy", from the Commodores’ 1977 self-titled album]. I know that it's always best when you use somebody else's song, but I wrote that song in a state of just that. I wasn't quite sure. I wasn't aware. The other song would be "Zoom" [from the same album]. The lyrics to that song basically sums up exactly where we all are. There's a place we'd all like to go and just hide for a moment to get away from all this craziness. I use those two songs as my mantras just because of the message that it gives.

That duality of "I'm telling you my story, but also we're all sharing this." I love it.

I think the entry of that was, "I may be just a foolish dreamer, but I don't care. All I know is my happiness is out there somewhere." We're all looking for that silver lining, that horizon that we've never seen before. When I wrote those lyrics, I must tell you, it was exactly the feeling of where we are now as a world. Because it was confusing. Think about it. This is the early ‘70s, coming out of the ‘60s, the craziness of Vietnam, and as a kid, what's out there for us? I don't know. What's the possibilities? We're not sure. And so here we are again, yet again faced with this survival of how do we stay sane in this world of insanity?

And how do we feed each other with things that feel nourishing?

What I love about the music business is that what determines a real hit record is when people walk up to you and go, "Lionel, I felt the same way." Now, that means you start realizing that, "Yes, I wrote a love song, but those words helped everybody else. That feeling that I felt is the feeling that everybody else felt."

So it's a confirmation that we're all human. We're all feeling. There are moments of happiness. There are moments of tragedy. And we're all doing this in the same world of trying to cope. And so I always say at the end of the day, there's got to be this common bond of humanity and mankind. There's got to be a thread of hope. Otherwise, we've lost the plot completely.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Khatia Buniatishvili Plays "Mephisto-Waltz No.1"

Peanut Butter Wolf Talks New Campus Christy Album & What's Next For Stones Throw

Warner Music Group's Paul Robinson To Be Honored With 2025 Entertainment Law Initiative Service Award

Your Vote, Your Voice: 6 Reasons Why Your GRAMMY Vote Matters

JOHNNYSWIM Reveal The Mic That Defines Their Sound

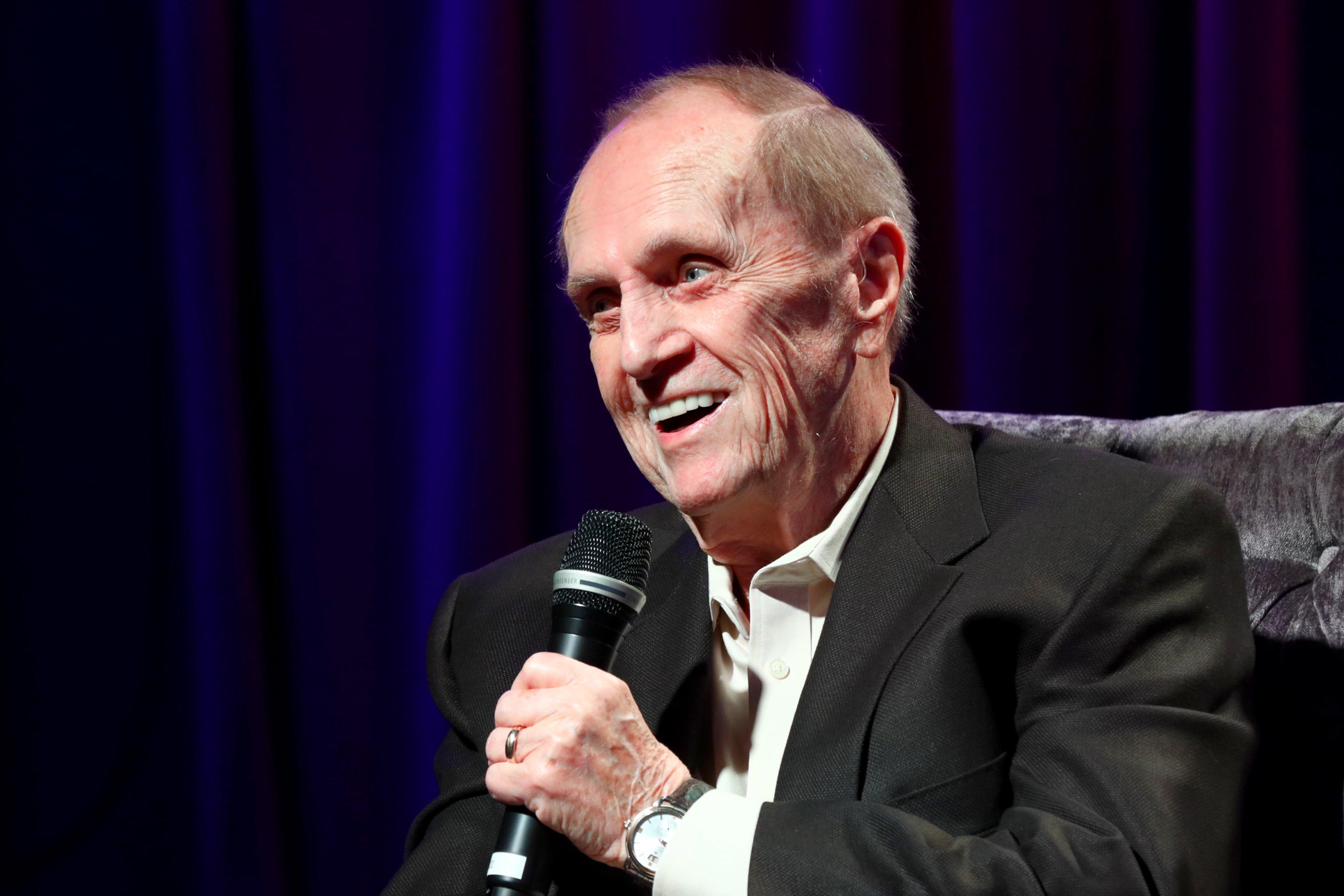

Photo: Rebecca Sapp/WireImage

news

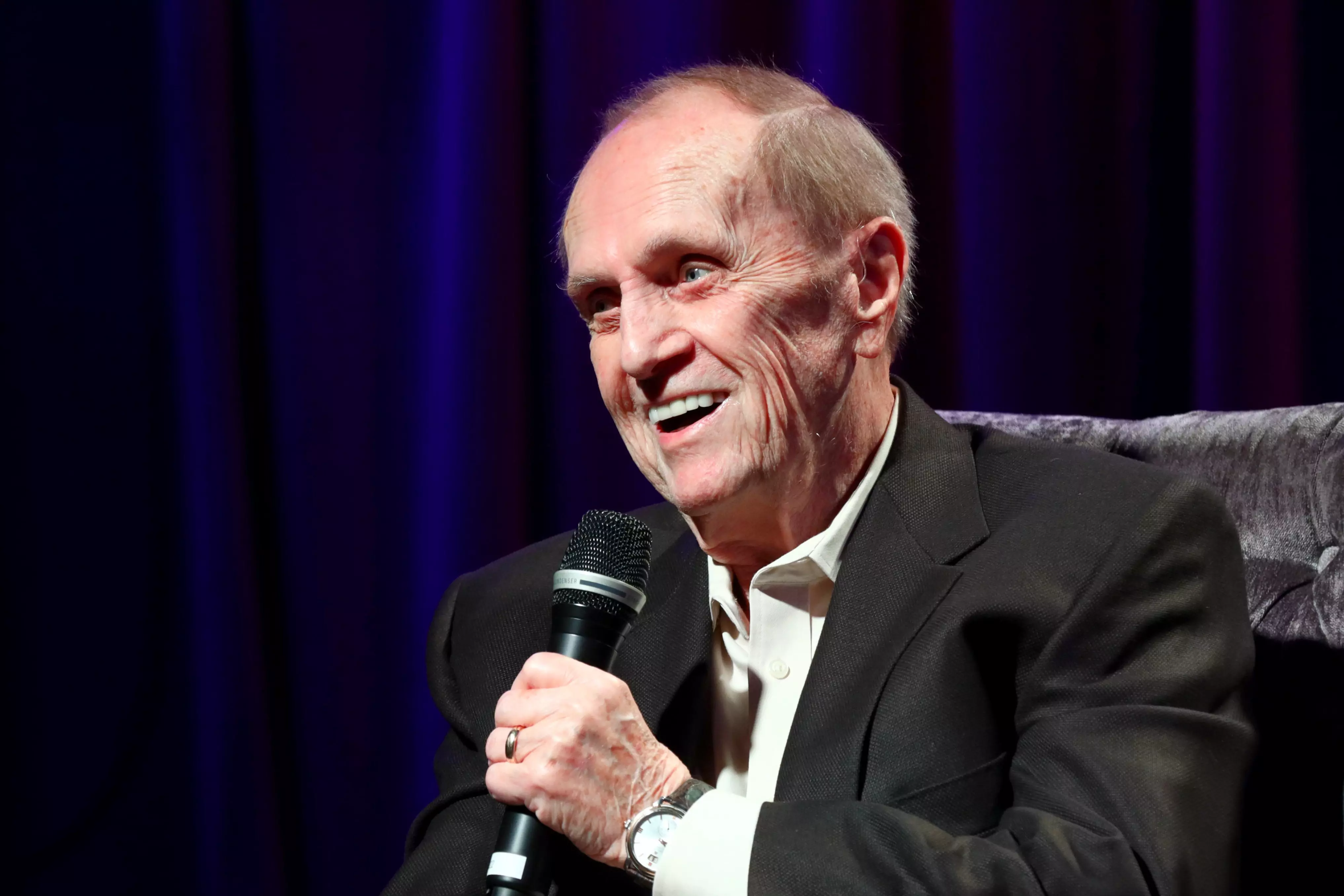

Remembering Bob Newhart, The Comic Who Made GRAMMY History With His Debut Album

The legendary comic, whose work onstage and on screen spanned multiple generations, passed away at age 94 on July 18.

Bob Newhart, one of the most celebrated comedians of his generation and renowned for his deadpan delivery died at his home in Los Angeles on July 18. He was 94.

Awarded the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts’ Mark Twain Prize for American Humor in 2002, Newhart launched his career with a record-setting record. By the time he transitioned to television with two successful sitcoms, he had become a household name.

Newhart made his vinyl debut on April Fool’s Day in 1960, when Warner Brothers Records released his first comedy album, The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart. A year later, at the 3rd GRAMMY Awards, the former accountant-turned-comic took home three golden gramophones.

At the 1961 GRAMMYs, Newhart won Album Of The Year — beating out two classical albums as well as works by Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra and Harry Belafonte. Newhart also won Best New Artist at that year's ceremony and, to this day, is the only comedian to win in both categories.

Recorded live on Feb. 10, 1960 at the Tidelands Motor Inn in Houston, Button Down Mind also became the first comedy audio album to reach No. 1 on the Billboard 200 chart. The album is widely considered to be one of the most consequential comedy albums of the 20th century and, fittingly, features the subtitle The Most Celebrated New Comedian Since Attila (the Hun).

The album was added to the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry in 1960. That year, The New York Times noted that Newhart was “the first comedian in history to come to prominence through a recording.” In 2007, the Recording Academy inducted The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart into the GRAMMY Hall of Fame.

His second album, The Button-Down Mind Strikes Back!, similarly topped the Billboard charts and earned Newhart his third GRAMMY Award, this time for Best Comedy Performance — Spoken Word.

Newhart received two additional GRAMMY nods during this illustrious career: His Button Down Concert album was nominated for Best Spoken Comedy Album at the 40th GRAMMY Awards, and nine years later his I Shouldn't Even Be Doing This! was nominated for Best Spoken Word Album.a

The success of Button-Down Mind led to the launch of Newhart's long TV career. His NBC variety show, "The Bob Newhart Shot" only lasted one season, but earned an Emmy for Outstanding Comedy Series in 1962. Newhart found greater success through CBS, which broadcast a series of the same name. On the second "The Bob Newhart Show," which ran from 1972 to 1978, the comic actor played a psychologist,

Four years later, he followed up with another sitcom, "Newhart," which aired until 1990 and in which Newhart played a Vermont innkeeper.

Bob Newhart has continued to have a presence on the small screen. His recording debut has been referenced in a variety of contemporary period shows, including "Mad Men" and "The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel."

During his decades-long television career, Newhart received nine EMMY nominations, including as Outstanding Lead Actor in a Comedy Series over three consecutive years for "Newhart" and three for Outstanding Guest Actor in a Comedy Series for his appearances on CBS’ "The Big Bang Theory."

Born George Robert Newhart on Sept. 5, 1929, in Oak Park, Illinois, Newhart graduated from Loyola University of Chicago in 1952 with a degree in accounting. After serving in the Army during the Korean War, he returned to Loyola for law school, but dropped out and pursued office work.

Newhart worked as an accountant for United States Gypsum Corp., which manufactures construction materials, and later as a copywrighter for Fred Niles Films Company in Chicago. During that time, Newhart began recording "long, antic" phone calls with a friend as audition tapes for comedy jobs. They caught the attention of a Chicago disc jockey, who introduced Newhart to the head of talent at Warner Bros. Records and which led to a life-changing contract in 1959.

It was in the latter category that Newhart won his first and only Emmy in 2013, 20 years after the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences inducted him into its Hall of Fame.

Remembering Legends & History-Makers

Remembering Quincy Jones: Musical Pioneer, Inspiration, Activist & Renaissance Man

Remembering Phil Lesh, Grateful Dead Co-Founder And Bassist With An Unbreakable Chain

Remembering Bob Newhart, The Comic Who Made GRAMMY History With His Debut Album

2024 GRAMMYs In Memoriam: Stevie Wonder, Lenny Kravitz & More Pay Tribute To Late Icons

Remembering Clarence Avant: The Black Godfather, Renowned Entertainment Mentor & Recording Academy Honoree