Photo: ©Nina Westervelt

news

Joni Mitchell To Make GRAMMY Performance Debut At The 2024 GRAMMYs

Joni Mitchell will perform at the GRAMMY Awards for the first time ever at the 2024 GRAMMYs on Sunday, Feb. 4. She joins previously announced GRAMMY performers Billie Eilish, Billy Joel, Burna Boy, Dua Lipa, Luke Combs, Olivia Rodrigo, Travis Scott & U2.

Already a cultural icon, Joni Mitchell is once again making music history next week: Joni Mitchell has just been announced as a performer at the 2024 GRAMMYs, marking her first-ever performance at the GRAMMY Awards. Mitchell is currently nominated at the 2024 GRAMMYs in the Best Folk Album Category for her 2023 live album, Joni Mitchell At Newport [Live], which was recorded at the 2022 Newport Folk Festival. The surprise performance at Newport marked her first performance in 20 years. In another first, Mitchell — a nine-time GRAMMY Award winner, the 2022 MusiCares Person of the Year honoree, and a Recording Academy Lifetime Achievement Award recipient, awarded in 2002 — will grace the GRAMMY stage on Sunday, Feb. 4, to deliver a history-making performance.

Mitchell now joins a massive lineup of 2024 GRAMMYs performers, which includes Billie Eilish, Billy Joel, Burna Boy, Dua Lipa, Luke Combs, Olivia Rodrigo, and Travis Scott. Recently announced performers U2 will also make GRAMMY history next week at the 2024 GRAMMYs where they will deliver a special performance from Sphere in Las Vegas, marking the first-ever broadcast performance from the first-of-its-kind, technologically groundbreaking venue; the event will also feature a special awards presentation. Additional performers will be announced in the coming days. See the full list of performers and host at the 2024 GRAMMYs to date.

Learn More: 2024 GRAMMY Nominations: See The Full Nominees List

2024 GRAMMYs: Explore More & Meet The Nominees

2024 GRAMMYs: See The Full Winners & Nominees List

How To Watch The 2024 GRAMMYs Live: GRAMMY Nominations, Performers, Air Date, Red Carpet, Streaming Channel & More

2024 GRAMMYs Performers: Burna Boy, Luke Combs And Travis Scott Announced

2024 GRAMMYs Performers: Billie Eilish, Dua Lipa, And Olivia Rodrigo Announced

Get The Full 2024 GRAMMYs Experience On Live.GRAMMY.com: Performances, Interviews, Red Carpet, Backstage & More

Here Are The Album Of The Year Nominees At The 2024 GRAMMYs

Here Are The Song Of The Year Nominees At The 2024 GRAMMYs

Get To Know The Best New Artist Nominees At The 2024 GRAMMYs

Here Are The Record Of The Year Nominees At The 2024 GRAMMYs

The 2024 GRAMMYs, officially known as the 66th GRAMMY Awards, will broadcast live from Crypto.com Arena in Los Angeles on Sunday, Feb. 4, at 8 p.m. ET/5 p.m. PT on the CBS Television Network and will be available to stream live and on demand on Paramount+.^ Prior to the Telecast, the GRAMMY Awards Premiere Ceremony will broadcast live from the Peacock Theater at 12:30 p.m. PT/3:30 p.m. ET and will be streamed live on live.GRAMMY.com. On GRAMMY Sunday, fans can access exclusive behind-the-scenes GRAMMY Awards content, including performances, acceptance speeches, interviews from the GRAMMY Live red-carpet special, and more via the Recording Academy's digital experience on live.GRAMMY.com.

Trevor Noah, the two-time GRAMMY-nominated comedian, actor, author, podcast host, and former "The Daily Show" host, returns to host the 2024 GRAMMYs for the fourth consecutive year; he is currently nominated at the 2024 GRAMMYs in the Best Comedy Album Category for his 2022 Netflix comedy special, I Wish You Would.

The 66th GRAMMY Awards are produced by Fulwell 73 Productions for the Recording Academy for the fourth consecutive year. Ben Winston, Raj Kapoor and Jesse Collins are executive producers.

^Paramount+ with SHOWTIME subscribers will have access to stream live via the live feed of their local CBS affiliate on the service, as well as on demand in the United States. Paramount+ Essential subscribers will not have the option to stream live but will have access to on-demand the day after the special airs in the U.S. only.

Photo: Tabatha Fireman/Getty Images for Fender Musical Instruments Corporation

interview

Living Legends: Thurston Moore On New Album 'Flow Critical Lucidity,' No Wave & His Place In Experimental Music History

"I tend to be a little more thorny, maybe a little more…I don't know, no wave sassy," Thurston Moore tells GRAMMY.com of his history as an indie rock songwriter. "Right now, I just want to stay in one place and continue writing."

Today, Thurston Moore unveiled his latest solo project, Flow Critical Lucidity, an album that encapsulates his signature guitar-driven charm and dives deep into his experimental roots.

The September 20 release marks another fascinating chapter in the illustrious career of an artist who has woven the tapestry of his music with the threads of New York's vibrant no wave scene since his teenage years in the mid-'70s.

Moore's journey has been one of constant evolution, intersecting with countless facets of New York's indie arts. From legendary gigs at CBGBs and the Mudd Club to watching William S. Burroughs stalk the neighborhood streets and being drafted into Glenn Branca’s guitar orchestra, his story is deeply embedded in the city's art mythos. Alongside then-partner Kim Gordon, Moore formed the legendary Sonic Youth eventually joined by Lee Ranaldo and Steve Shelley. Through decades, lineup shifts, 15 LPs and countless experimental releases, the band transcended the boundaries of punk and outsider art, drawing influences from figures as diverse as Joni Mitchell and John Cage.

Their 1988 release, Daydream Nation, is likely their best-known, an epic triumph beloved by adventurous fans worldwide that has placed on countless "greatest albums ever" lists and influenced musicians and artists of many different disciplines.

Even when his work had made its way to major labels and international acclaim, Moore has never shied away from the avant-garde — from hours of guitar feedback to audacious records where he and his bandmates hammer nails into piano keys. From "Teen Age Riot" to "Kool Thing", and "100%," he’s co-written some of the most iconic indie rock songs of a generation as part of Sonic Youth and has also released pieces that question the very definition of music.

Both during and after the dissolution of Sonic Youth, and following his move from New York to London — where he runs the book publishing house Ecstatic Peace Library and the record label Daydream Library Series with his partner, Eva Prinz — Moore's voracious appetite for creating new, exciting art persists. Flow Critical Lucidity exemplifies this relentless pursuit, bridging past influences with futuristic sounds in a sublime stretch of spacey rock.

Every conversation with Moore reveals an encyclopedic knowledge of experimental art and more inspiring anecdotes than one could dream of — and this one is no different.

As Moore prepares for the release, GRAMMY.com caught up with him to reflect on his storied career and ever-changing landscape of experimental art, the history of no wave cinema, his evolving assessment of his own vocals, and his decision to say goodbye to New York.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

The art for your new album is based on a Jamie Nares piece, and I know you mention her in your memoir alongside no wave filmmakers like Vivienne Dick and Scott B and Beth B — a scene that you described as "a community that became only more alluring to me in their smart and erotic subversion." I mean, even just reading that is appealing.

Yeah. Downtown New York in the late '70s had the initial CBGB and Max's punk scene with Patti [Smith] and Blondie and Talking Heads, Ramones and Television, Richard Hell. There was a concurrent community of younger artists and musicians, and they got tagged with the genre of being no wave. And no wave wasn't something that came out of punk or new wave. It actually coexisted as even more challenging music. Punk really was a rock and roll music, whereas no wave was absolutely not a rock and roll music. It was just using the instrumentation of it, but the players were approaching the instruments without any semblance of traditional tropes.

That fascinated a lot of people who were already in New York City, downtown, in the art scene coming out of minimalist and conceptual art practices. Some of these artists are filmmakers, and they're very attracted to these bands that are creating a new way of playing music in complete resistance to the standards of expectation with traditionalism. No wave becomes a real pride of definition for them in some of the visual art. Super 8 and 16 millimeter movie cameras were affordable cameras. The film was somewhat affordable from certain film labs downtown. And you could make either silent, or if you're really audacious, sound movies that weren’t expensive. It wasn't any more expensive than making a 7-inch. And so these no wave filmmakers had a space on St. Mark's Place, just a ratty little storefront where they would show these movies. Some were better than others, let's put it that way, but the idea was that they were doing it and it was being done fast and it was using just the local people on the scene as actors. And some of them became serious filmmakers. I mean, Jim Jarmusch came out of that scene.

Jamie Nares was living in Manhattan and making these interesting films at the time, utilizing some of the no wave musicians as actors and actresses. Her films had a certain character about them because she had a really specific focus on what she wanted to present. It wasn't just having fun and slapdash. Some of the films were really affecting and really interesting. Also, if you look at the back of No New York, the compilation album that Brian Eno recorded of some of the bands on the downtown scene at that point, Jamie was the first guitar player in the Contortions.

What was it about Nare's work specifically that really burrowed into you and led to this cover?

Well, the work actually on the cover of the record is maybe not that indicative of what people usually know about Jamie Nares today. A lot of her work is really in the realm of painting, fairly large canvases with huge swaths of energy, paint streaking across them. They're very dancey and poetic.

I went to her retrospective [in Milwaukee], and noticed that some of her earlier sculptures were there, and one of them was that helmet with the tuning forks sticking out of it. I just thought it was so evocative and beautiful, this idea of taking a military implement and recontextualizing it as an article of communication and music. Jamie’s piece is called "Samurai Walkman," and I toyed with calling the album that. But I really liked calling the record Flow Critical Lucidity, taken from a lyric Eva [Prinz] had written. She wrote lyrics to five out of the seven songs on the record. The line reminded me of something that would come out of the pen of Mark E. Smith of the Fall. Even though that's the last thing I think Eva was considering. She writes under the pseudonym Radieux Radio, and always has, since The Best Day record in 2014. It's been really wonderful because it's this other voice that I get to work with. It's a voice that's decidedly not a white male voice. It's a feminist voice. And I really embrace that because I think that really gives the music that much more strength.

What do you appreciate most about Eva's purview as a writer and lyricist?

There's a certain joy to the intellect of nature that she is able to put into words that I find really endearing and alluring and smart. I tend to be a little more thorny, maybe a little more…I don't know, no wave sassy. I'll add a little bit to what she does and vice versa. It's a really great collaboration. We collaborate mostly on publishing books. She was a senior book editor at Rizzoli, Abrams, and Taschen. So that to me is really enjoyable, publishing books and actually putting some records up by new bands.

What else do you have on tap?

Well, this record of mine is on our label, Daydream Library [Series]. We put out a new record by Devon Ross, a young singer/songwriter from Los Angeles. She's an actress and a model, and she was in this limited TV series called "Irma Vep" that the filmmaker Olivier Assayas made for HBO with Alicia Vikander. I met her at screenings and she said she had music. People send me music all the time, and I'm usually like, "Yeah, sure." There's not that much I'm that interested in facilitating. I used to put a lot of records out through the '80s and '90s, but when we moved to London, I cooled down on it. And then we saw this band called Big Joanie, which was these three Black English girls who have a really amazing political punk band. We put out their first two records, and now Devon Ross is the latest that we put out.

Eva listened to it first and said, "It's really good." I listened to it and I agreed. We put an EP out, and it's become really buzzy. She has this great band, and it's really just noisy, sonic punk pop music. There's a couple of bands in Miami that we put records out by. There's a shoegaze Caribbean kind of band called the Sea Foam Walls I really like. And there's an all-girl band there called Las Nubes, which means the clouds en español. They sing in Spanish and English, and they're very much part of the Miami punk scene that is primarily bilingual. We put out a record by the drummer of the Ex, the anarcho-punk band from Holland… we put out a CD of her sound healing music.

We put out whatever we want. We're just an indie label out of our London flat, and we make books whenever we get enough coin to do something. We've done a few memoirs, one by David Toop, an experimental musician here in London. We're doing another one with Maggie Nicols, who since the late '60s has been in the forefront of free improvisation music here in England. We keep ourselves busy, but we try not to stretch ourselves too thin at the same time.

Right now, I just want to stay in one place and continue writing because I really enjoyed writing the memoir. And now I'm heads down, putting the finishing touches on a novel that I hope to get published, if somebody bites. It takes place in the early '80s in downtown New York City, just characters.

I bet that in its own way there’s some memoir to that, too.

A little bit, yeah, a little bit. I certainly realized that I had to place it in an environment that I could be intimate with.

When you’re back in New York City and walking around, is it recognizable at all to you from 50 years ago?

Especially the deeper in the Lower East Side you go, there are certain walls or corners where you can flash back on the '70s, early '80s. The city was far dirtier then, a little more lawless. And in that respect, you never really felt that safe. But when you're young, it's like you're somewhat invincible anyway. So I don't really miss it at the age I am now. I'd rather be living underneath an olive tree somewhere in northern Italy than having to live on East Broadway or something. But it's also a matter of financial stability. If somebody offered me some fabulous place in Manhattan, or anywhere in New York City, free of charge, I might swoop on it.

But I like living in London. We really love it. There's no guns here really. That's a real plus. I'm just really waiting to see what the elections are going to be in November as far as how safe I feel the USA is because I have such anxiety about that. We're flying in the day before the election just to vote.

I know you’ve shared that you’re dealing with a heart condition, too. Has that cleared to the point that you can travel?

Another reason why I'll be coming in at the end of the year is because I still have to go under the knife a bit. But it's nothing critical. It's just an ablation thing. People have AFib [atrial fibrillation] and irregular heartbeats and stuff, and sometimes you have to go in there and put a stent in. It's an operation that's done all day every day. Its success rate is 99%. I have more of a chance of falling out the window tonight. It still means that I can't do too much else. So I'm not going to really be doing much touring. But like I said, I prefer actually writing. I want to get into writer mode more so than getting into a van and crisscrossing the planet and playing in beer halls. I've done that a lot.

I'll play some specific shows as long as they are interesting. I like playing in special places like in churches, and certain festivals are cool.

Can you talk about building the sound on Flow Critical Lucidity? There are parts of it that conjure The Stooges’ "We Will Fall," or something like that.

Yeah, it does have that vibe. I demoed a lot of it on a small digital recorder that I figured out how to use because I'm pretty much a Luddite with this stuff. I allowed the musicians to create parts to what I was doing. I was using digital drum patterns just so I could have a drum pattern, and sometimes I would pick these really weirdo drum patterns. So something like the song "We Get High" has that "We Will Fall" drum rhythm. And my drummer, Jem Daulton, listened to that and he recreated it himself, or at least what that vibe was. We used a studio called Total Refreshment Centre in North London that the Chicago label International Anthem uses as their English studio. It has that kind of new cosmic dub vibe.

Then there’s Jon Leidecker, who's an electronics musician who's in the band, he's actually processing some of the inputs and outputting them in a specific way and adding some electronic flourishes. He records under the name Wobbly and is a member of Negativland. That, and also the engineer, Margo Broom, was really instrumental in how that record sounded. She had recorded, mixed, and mastered Big Joanie, and I really liked how those records were sounding. She's a genius, and she really made this record sound the way it sounds. Watching her work, she was just so smart and so expedient, and she really knew my history as a musician. Even working with the vocals, I always hate my vocals because I feel like I'm being very challenged by how to stay in key to all this finicky music. I was really impressed how she was treating the vocals and making it work. And she said, "Well, I've been listening to your vocals since I was 10 years old."

How did you treat singing back in the '80s? Were you just not self-conscious about it? Because you sound comfortable on this.

It was through fits and starts that I had some realization of how to present myself as a vocalist. I never felt like I reached a point where I feel like I am comfortable with it, and I regret not actually focusing on that more seriously as I did with everything else. When it came to getting on the mic, I just thought, well, it's either going to work or it's not. And then I realized, no, there's a lot of discipline. There's a lot of practice that you can put into this. When I see Nick Cave sit down at a piano and start singing, it’s clear this is somebody who's really focused on how to be a singer. I regret that I didn't focus more on that because I think there's such a power there.

Read more: Nick Cave Returns With The Bad Seeds To Plant Joyful Noise

When you would see punk bands in the late '80s, early '90s, it was like, "Okay, the singers can be good, or they can be not so good, but the collective is what it's all about." But at the same time, a band like Nirvana comes out, and they’re a great band, but they’re not altogether that different from a lot of other bands that they associated with. What's really raising the level is that singer's voice and how that singer is getting on the microphone. Kurt's voice was just something else entirely. Nobody was singing like that. When I first heard him, I was like, "Oh, he's doing a Lemmy from Motörhead thing but in the context of a Pacific Northwest punk thing. That's brilliant." But it was so much more than that because it was soul shredding and it was beautiful.

So I always thought, in my case, I can be a serviceable singer more than a remarkable singer. There's only a few people who can be remarkable singers. It's like wanting to speak another language. I wish I could speak another language. I wish I could sing with the same astounding resonance as Billie Holiday or Joni Mitchell. But I ignored that.

I'm very conscious of that when I make a record now. Like, "I'm going to do my best here." But when I listen to live tapes, I'm just like, "Man, nobody's going to get fooled into thinking that I'm Jim Morrison." I used to complain about Steve Albini's vocal mixes. It was all about really slamming drums and guitars and stuff like that. And I love Steve, but I was like, "The vocals kind of suffer because everything else is just blasting." And his response was, "Well, listen, most of these singers I record, very few of them are Paul McCartneys." And he's right about that. But also it's like, "Well, maybe you should try to make them Paul McCartneys. Let's figure this out. Take some singing lessons."

Read more: Without Steve Albini, These 5 Albums Would Be Unrecognizable: Pixies, Nirvana, PJ Harvey & More

Back in 1985 or '86, we were doing some gig and this musician came up to me and she goes, "There’s nothing wrong with taking singing lessons. You should try singing and not screaming or shouting." I was really just in shock. I was like, "Wow. I never even thought about that." Early on, I was just yelling into the microphone. Of course, there was a lot of din going on on stage. You had to yell to get heard because the sound systems couldn't deal with the blasting guitar noise. But it made me think, "You're right, that would make it better."

I assumed this would be a long answer so I saved it for the end, but what are you listening to and reading lately that’s turning you on?

I take cues from other young poets that I see in social media sharing what they're reading and then sending away for those books. I love that whole culture of literature. There's a lot of mainstream literature I think is great. I think Colson Whitehead continues to be one of the great writers that we have in the USA, if not the world. Even this trio of genre novels that he's been working on, that second one, Harlem Shuffle, was really, really fun to read and really extremely artful and for me, a great course in how to write fiction, just by reading a book like that.

And listening, I know I just constantly take cues again from different people I entrust with their tastes of buying records on Bandcamp. I generally tend towards buying more experimental music, the whole continuing underground aesthetics that you might hear coming out of the Wolf Eyes world. I still think that's where some great music is happening. I don't really listen to too much straight ahead, compositional rock and roll music. I feel like I've so decoded a lot of that kind of songwriting that I don't find myself listening to it for any sense of wonder.

Sometimes I'll spend an hour or two just putting things on, playing them at a commanding volume, and I'll just sit there and look at the record cover. Sometimes it leads me into being really intrigued by other people on the record, and I'll go into Discogs and find out all the other work they've done. That's what I really adore about the internet. You can actually do this research while you're processing the work. The internet was always an ideal coming out of the hippie mindset anyway, wasn't it? It's just been corporatized and monetized beyond any recognition of such a thing. But it does exist.

More Alternative Music News

Chelsea Cutler & Jeremy Zucker On Why 'Brent iii' Is "A Nice Way To Close The Page" On Their Musical Partnership

The Linda Lindas Talk 'No Obligation,' Cats & Working With Weird Al

Why BoyWithUke Is Already Retiring His Alter Ego

Get To Know Declan McKenna, The British Rocker Shaking Up The Indie Scene

Radiohead Performs "15 Step" At The 2009 GRAMMYs

Graphic Courtesy of CBS

news

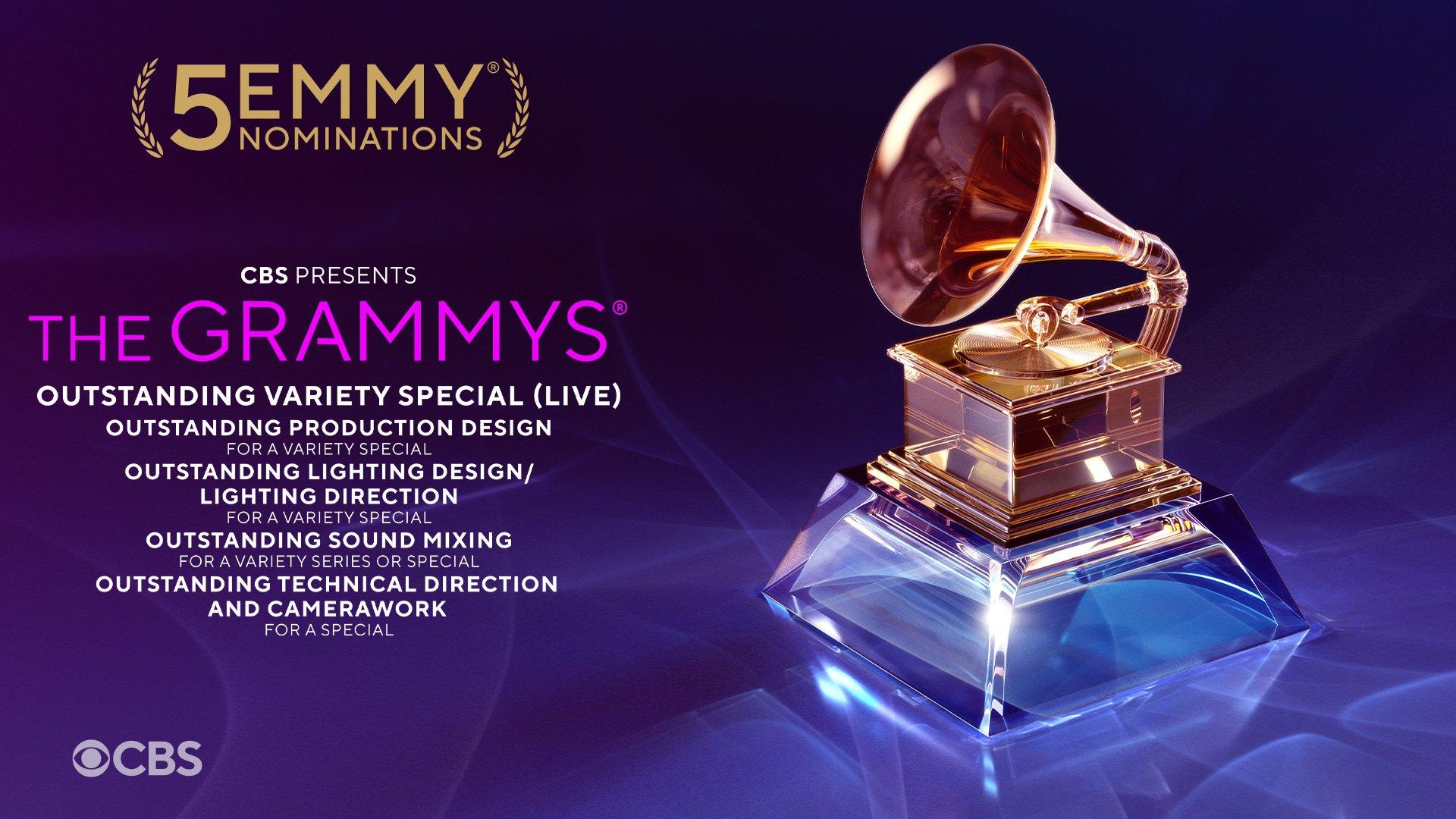

The 2024 GRAMMYs Have Been Nominated For 5 Emmys: See Which Categories

The 2024 GRAMMYs telecast is nominated for Outstanding Variety Special (Live), Outstanding Production Design For A Variety Special, and three more awards at the 2024 Emmys, which take place Sunday, Sept. 15.

It’s officially awards season! Today, the nominees for the 2024 Emmys dropped — and, happily, the 2024 GRAMMYs telecast received a whopping five nominations.

At the 2024 Emmys, the 2024 GRAMMYs telecast is currently nominated for Outstanding Variety Special (Live), Outstanding Production Design for a Variety Special, Outstanding Lighting Design/Lighting Direction for a Variety Special, Outstanding Sound Mixing for a Variety Series or Special, and Outstanding Technical Direction and Camerawork for a Special.

Across these categories, this puts Music’s Biggest Night in a friendly head-to-head with other prestigious awards shows and live variety specials, including the Super Bowl LVIII Halftime Show starring Usher as well as fellow awards shows the Oscars and the Tonys.

2024 was a banner year for the GRAMMYs. Music heroes returned to the spotlight; across Categories, so many new stars were minted. New GRAMMY Categories received their inaugural winners: Best African Music Performance, Best Alternative Jazz Album and Best Pop Dance Recording. Culture-shaking performances and acceptance speeches went down. Those we lost received a loving farewell via the In Memoriam segment.

The 2025 GRAMMYs will take place Sunday, Feb. 2, live at Crypto.com Arena in Los Angeles and will broadcast live on the CBS Television Network and stream live and on demand on Paramount+. Nominations for the 2025 GRAMMYs will be announced Friday, Nov. 8, 2024.

For more information about the 2025 GRAMMY Awards season, learn more about the annual GRAMMY Awards process, read our FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions) section, view the official GRAMMY Awards Rules and Guidelines, and visit the GRAMMY Award Update Center for a list of real-time changes to the GRAMMY Awards process.

2025 GRAMMYs: Meet The Nominees

2025 GRAMMYs: See The OFFICIAL Full Nominations List

Watch The 2025 GRAMMY Nominations Announcement Now

2025 GRAMMYs Nominations: Album Of The Year Nominees

2025 GRAMMYs Nominations: Song Of The Year Nominees

2025 GRAMMYs Nominations: Best New Artist Nominees

2025 GRAMMYs Nominations: Record Of The Year Nominees

2025 GRAMMYs Nominations: Producer Of The Year Nominees

2025 GRAMMYs Nominations: Songwriter Of The Year Nominees

2025 GRAMMY Nominations: See Shaboozey, Anitta, Teddy Swims & More Artists' Reactions

Beyoncé & Taylor Swift Break More GRAMMY Records, Legacy Acts Celebrate Nods & Lots Of Firsts From The 2025 GRAMMY Nominations

2025 GRAMMYs Nominations: Best African Music Performance Nominees

Who Are The Top GRAMMY Awards Winners Of All Time? Who Has The Most GRAMMYs?

How Much Is A GRAMMY Worth? 7 Facts To Know About The GRAMMY Award Trophy

The Impact Of A GRAMMY Win: Life After The Award

2025 GRAMMYs To Take Place Sunday, Feb. 2, Live In Los Angeles; GRAMMY Awards Nominations To Be Announced Friday, Nov. 8, 2024

GRAMMY Awards Updates For The 2025 GRAMMYs: Here's Everything You Need To Know About GRAMMY Awards Categories Changes & Eligibility Guidelines

Recording Academy Renames Best Song For Social Change Award In Honor Of Harry Belafonte

The Recording Academy Adds More Than 3,000 Women GRAMMY Voters Since 2019, Surpassing Its 2025 Membership Goal

Photo: Jathan Campbell

list

How Much Is A GRAMMY Worth? 7 Facts To Know About The GRAMMY Award Trophy

Here are seven facts to know about the actual cost and worth of a GRAMMY trophy, presented once a year by the Recording Academy at the GRAMMY Awards.

Since 1959, the GRAMMY Award has been music’s most coveted honor. Each year at the annual GRAMMY Awards, GRAMMY-winning and -nominated artists are recognized for their musical excellence by their peers. Their lives are forever changed — so are their career trajectories. And when you have questions about the GRAMMYs, we have answers.

Here are seven facts to know about the value of the GRAMMY trophy.

How Much Does A GRAMMY Trophy Cost To Make?

The cost to produce a GRAMMY Award trophy, including labor and materials, is nearly $800. Bob Graves, who cast the original GRAMMY mold inside his garage in 1958, passed on his legacy to John Billings, his neighbor, in 1983. Billings, also known as "The GRAMMY Man," designed the current model in use, which debuted in 1991.

How Long Does It Take To Make A GRAMMY Trophy?

Billings and his crew work on making GRAMMY trophies throughout the year. Each GRAMMY is handmade, and each GRAMMY Award trophy takes 15 hours to produce.

Where Are The GRAMMY Trophies Made?

While Los Angeles is the headquarters of the Recording Academy and the GRAMMYs, and regularly the home of the annual GRAMMY Awards, GRAMMY trophies are produced at Billings Artworks in Ridgway, Colorado, about 800 miles away from L.A.

Is The GRAMMY Award Made Of Real Gold?

GRAMMY Awards are made of a trademarked alloy called "Grammium" — a secret zinc alloy — and are plated with 24-karat gold.

How Many GRAMMY Trophies Are Made Per Year?

Approximately 600-800 GRAMMY Award trophies are produced per year. This includes both GRAMMY Awards and Latin GRAMMY Awards for the two Academies; the number of GRAMMYs manufactured each year always depends on the number of winners and Categories we award across both award shows.

Fun fact: The two GRAMMY trophies have different-colored bases. The GRAMMY Award has a black base, while the Latin GRAMMY Award has a burgundy base.

Photos: Gabriel Bouys/AFP via Getty Images; Frederick M. Brown/Getty Images

How Much Does A GRAMMY Weigh?

The GRAMMY trophy weighs approximately 5 pounds. The trophy's height is 9-and-a-half inches. The trophy's width is nearly 6 inches by 6 inches.

What Is The True Value Of A GRAMMY?

Winning a GRAMMY, and even just being nominated for a GRAMMY, has an immeasurable positive impact on the nominated and winning artists. It opens up new career avenues, builds global awareness of artists, and ultimately solidifies a creator’s place in history. Since the GRAMMY Award is the only peer-voted award in music, this means artists are recognized, awarded and celebrated by those in their fields and industries, ultimately making the value of a GRAMMY truly priceless and immeasurable.

In an interview featured in the 2024 GRAMMYs program book, two-time GRAMMY winner Lauren Daigle spoke of the value and impact of a GRAMMY Award. "Time has passed since I got my [first] GRAMMYs, but the rooms that I am now able to sit in, with some of the most incredible writers, producers and performers on the planet, is truly the greatest gift of all."

"Once you have that credential, it's a different certification. It definitely holds weight," two-time GRAMMY winner Tariq "Black Thought" Trotter of the Roots added. "It's a huge stamp as far as branding, businesswise, achievement-wise and in every regard. What the GRAMMY means to people, fans and artists is ever-evolving."

As Billboard explains, artists will often see significant boosts in album sales and streaming numbers after winning a GRAMMY or performing on the GRAMMY stage. This is known as the "GRAMMY Effect," an industry phenomenon in which a GRAMMY accolade directly influences the music biz and the wider popular culture.

For new artists in particular, the "GRAMMY Effect" has immensely helped rising creators reach new professional heights. Samara Joy, who won the GRAMMY for Best New Artist at the 2023 GRAMMYs, saw a 989% boost in sales and a 670% increase in on-demand streams for her album Linger Awhile, which won the GRAMMY for Best Jazz Vocal Album that same night. H.E.R., a former Best New Artist nominee, saw a massive 6,771% increase in song sales for her hit “I Can’t Breathe” on the day it won the GRAMMY for Song Of The Year at the 2021 GRAMMYs, compared to the day before, Rolling Stone reports.

Throughout the decades, past Best New Artist winners have continued to dominate the music industry and charts since taking home the GRAMMY gold — and continue to do so to this day. Recently, Best New Artist winners dominated the music industry and charts in 2023: Billie Eilish (2020 winner) sold 2 million equivalent album units, Olivia Rodrigo (2022 winner) sold 2.1 million equivalent album units, and Adele (2009 winner) sold 1.3 million equivalent album units. Elsewhere, past Best New Artist winners have gone on to star in major Hollywood blockbusters (Dua Lipa); headline arena tours and sign major brand deals (Megan Thee Stallion); become LGBTIA+ icons (Sam Smith); and reach multiplatinum status (John Legend).

Most recently, several winners, nominees and performers at the 2024 GRAMMYs saw significant bumps in U.S. streams and sales: Tracy Chapman's classic, GRAMMY-winning single "Fast Car," which she performed alongside Luke Combs, returned to the Billboard Hot 100 chart for the first time since 1988, when the song was originally released, according to Billboard. Fellow icon Joni Mitchell saw her ‘60s classic “Both Sides, Now,” hit the top 10 on the Digital Song Sales chart, Billboard reports.

In addition to financial gains, artists also experience significant professional wins as a result of their GRAMMY accolades. For instance, after she won the GRAMMY for Best Reggae Album for Rapture at the 2020 GRAMMYs, Koffee signed a U.S. record deal; after his first GRAMMYs in 2014, Kendrick Lamar saw a 349% increase in his Instagram following, Billboard reports.

Visit our interactive GRAMMY Awards Journey page to learn more about the GRAMMY Awards and the voting process behind the annual ceremony.

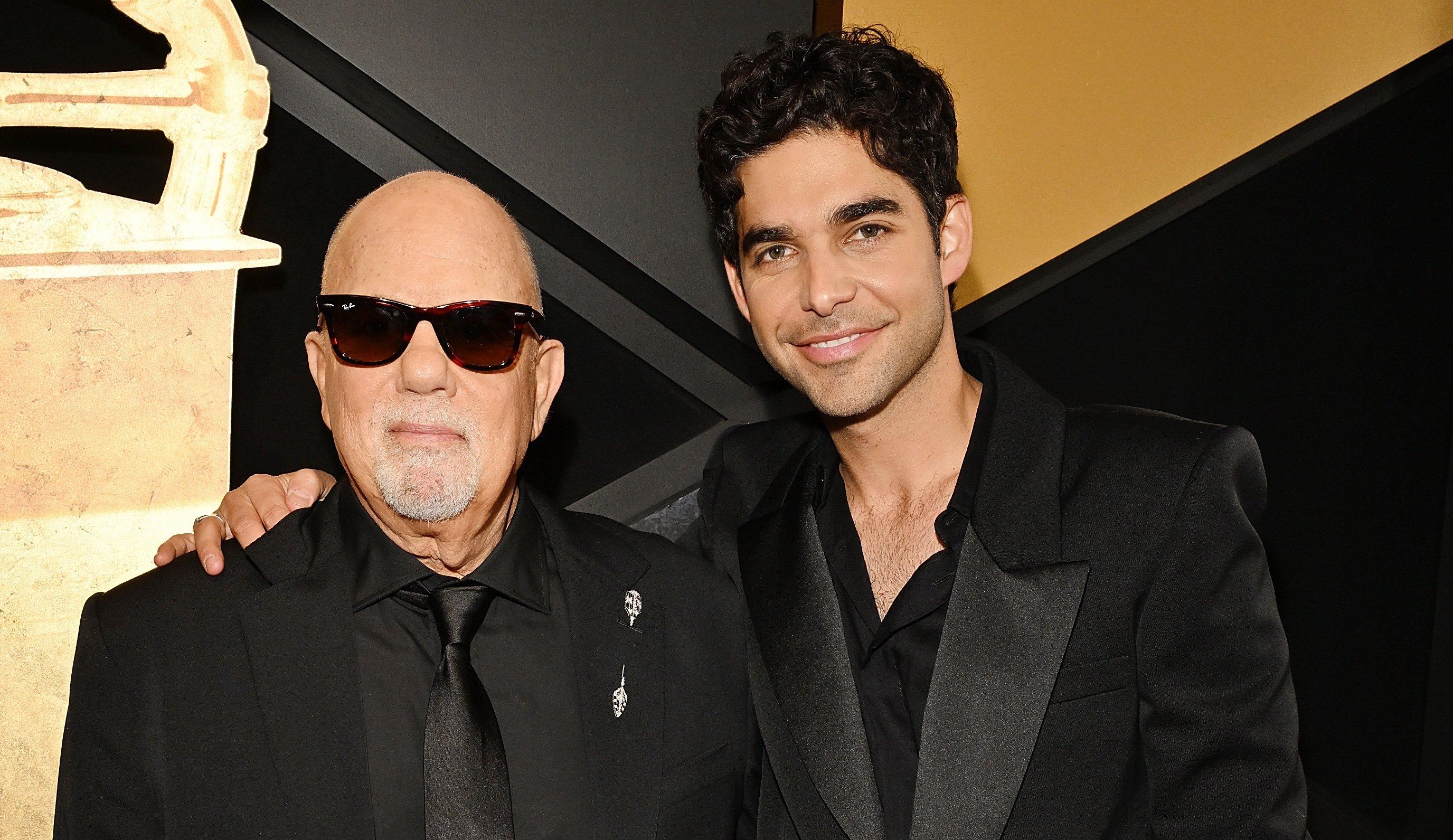

(L-R) Billy Joel, Freddy Wexler

interview

Freddy Wexler On Helping Billy Joel "Turn The Lights Back On" — At The 2024 GRAMMYs And Beyond

"Part of what was so beautiful for me to see on GRAMMY night was the respect and adoration that people of all ages and from all genres have for Billy Joel," Wexler says of Joel's 2024 GRAMMYs performance of their co-written "Turn The Lights Back On."

They say to not meet your heroes. But when Freddy Wexler — a lifelong Billy Joel fan — did just that, it was as if Joel walked straight out of his record collection.

"I think the truth is none of it is that surprising," the 37-year-old songwriter and producer tells GRAMMY.com. "That's the best part. From his music, I would've thought this is a humble, brilliant everyman who probably walks around with a very grounded perspective, and that's exactly who he is."

That groundedness made possible "Turn the Lights Back On" — the hit comeback single they co-wrote, and Wexler co-produced; Joel performed a resplendent version at the 2024 GRAMMYs with Laufey. Joel hadn't released a pop album since 1993's River of Dreams; for him to return to the throne would take an awfully demonstrative song, true to his life.

"I think it's a very raw, honest, real perspective that is true to Billy," Wexler explains. "I think it's the first time we've heard him acknowledge mistakes and regret in quite this way."

Specifically, Joel's return highlights his regret over spending three decades mostly on the bench, largely absent from the pop scene. As Joel wonders aloud in the stirring, arpeggiated chorus, "Is there still time for forgiveness?"

"Forgiveness" is a curious word. Why would the five-time GRAMMY winner and 23-time nominee possibly need to seek forgiveness? Regardless — as the song goes — he's "tryin' to find the magic/ That we lost somehow." The song's message — an attempt to recapture a lost essence — transcends Joel's personal headspace, connecting with a universal longing and nostalgia.

Read on for an interview with Wexler about the impact of "Turn the Lights Back On," why he thinks Joel took such an extended sabbatical, the prospect of more new music, and much more.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

**You did a great interview with Rolling Stone ahead of the 2024 GRAMMYs. Now, we're on the other side of it; you got to see how it went down on the telecast, and resonated with the audience and world. What was that like?**

It's why I make music — to hopefully make people feel something. This song has really resonated in such a big way. More than looking at its commercial success on the charts or on radio, which has been awesome to see, the comments on Instagram and YouTube have been the most rewarding part of it.

Why do you think it resonated? Beyond the king picking up his crown again?

I don't think the song is trying to be anything it's not. I think it's a very raw, honest, real perspective that is true to Billy. I think it's the first time we've heard him acknowledge mistakes and regret in quite this way. And to hear him do it in a hopeful way where he's asking, "Is it too late for forgiveness?" is just very moving, I think.

Forgiveness? That's interesting. What would any of us need to forgive him?

He has said in other interviews, "Sometimes people say they have no regrets at the end of their life." And he said, "I don't think that's possible. If you've lived a full life, of course you have regrets." He has said that he has many things he wishes he would've done differently. This is an opportunity to express that.

I think what's interesting about the song is it has found meaning in various ways with various people and listeners. Some people imagine Billy is singing to former lovers or friends. Other people imagine Billy is singing to his fans asking, "Did I wait too long to record again?" Other people wonder if Billy is singing to the songwriting Gods and muses. Did I wait too long to write again?

In Israel, where the song was number one — or is number one, I haven't checked today — I think the song's taken on the meaning of just wanting things to be normal, wanting hostages to come home and turn the lights back on. So, you never know where a song is going to resonate, but I think that Billy just found his own meaning with it.

You know the discography front to back. What lines can you draw from "Turn the Lights Back On" to past works?

I think it draws on various pieces of his catalog, right? "She's Always a Woman" has a sort of piano arpeggio in the chorus. To me, it feels like a natural progression. It feels like, on the one hand, it's a new song. On the other, it could have come out right after River of Dreams. To me, it just kind of feels natural.

**Back when you spoke with Rolling Stone, you said you couldn't wait to hear "Turn the Lights Back On" at Madison Square Garden. How'd it sound?**

Amazing. Billy is a consummate live performer. I think he's one of the few artists where everything is better live, and everything is always a little bit different each time it's played live.

It's been really cool to watch Billy and the band continue to change and improve the song and the song's dynamics for the show. He told me tonight that tomorrow night in Tampa, I think they're going to try to play with the key of the song, potentially — try it a half a step higher.

Those are the sort of things I think great artists do, right? It's different from being on a certain type of tour where every single song is the same, the set list is the same, the key is the same, the arrangements are the same.

With Billy, there's a lot of feeling and, "Hey, why don't we try it this way? Let's play it a little faster. Let's play it a little slower. Let's try it in a different key." I just think that's super cool. You have to be a really good musician to just do that on the fly.

What have you learned from him that applies to your music making, writ large?

I've learned so much from him. As Olivia Rodrigo said to us at GRAMMY rehearsals, "He's the blueprint when it comes to songwriting."

He has helped raise the bar for me when it comes to melodies and lyrics, but the thing I keep coming back to is he's reminded me that even the greatest artists and songwriters ever sometimes forget how great they are. I think we need to be careful not to give that inner voice and inner critic too much power.

Can you talk about how the music video came to be?

Well, I had a dream that Billy was singing the opening two lines of the song, but it was a 25-year-old version of Billy. It was arresting.

When I woke up, I sort of had the vision for the video, which was one set, an empty venue of some kind, and four Billy Joels. The Billy Joel that really exists today, but then three Billys from three iconic eras where each Billy would seamlessly pick up the song where the other left off.

The idea behind that was to sort of accentuate the question of the song — did I wait too long to turn the lights back on?

And so, to kind of take us through time and through all these years, I teamed up with an amazing co-director, Warren Fu, who's done everything from Dua Lipa to Daft Punk, and an artificial intelligence company called Deep Voodoo to make that vision possible.

What I'm driven by is the opportunity to create conversations, cultural moments, things that make people feel something. What was cool here is as scary as AI is — and I think it is scary in many ways — we were able to give an example of how you can use it in a positive way to execute a creative artistic vision that previously would've been impossible to execute.

Yeah, so I'm pleased with it and I'm thankful that Billy did a video. He didn't have to do one, but he liked the idea of it. He felt it was different, and I think he was moved by it as well.

What do you think is the next step here?

It's been a really rewarding process. And Billy is open-minded, which is really cool for an artist of that level, who's not a new artist by any stretch. To actually be described as being in a place in his life where he's open-minded, means anything is possible. I could tell you that I would love there to be more music.

I'd love to get your honest appraisal. And I know you're not him. But his last pop album was released 31 years ago. In that long interim, what do you think was going on with him, creatively?

Look, I'm not Billy Joel, but I think there were a number of factors going on with him. Somewhere along the way, I think he stopped having fun with music, which is the reason he got into it, or which is a big part of the reason he got into it. When it stopped being fun, I don't think he really wanted to do it anymore.

Another piece to it is that Billy is a perfectionist, and that perfectionism is evident in the caliber of his songwriting. Having always written 100 percent of his songs, Billy at some point probably found that process to be painstaking, to try to hit that bar where he's probably wondering in his head, What would Beethoven think of this? What would Leonard Bernstein think of this?

I think part of what was different here was that, perhaps, there was something liberating about "Turn the Lights Back On" being a seed that was brought to Billy. In this way, he could be a little disconnected from it, where maybe he didn't have to have the self-imposed pressure that he would if it was an idea that he'd been trying to finish for a while.

Ironically, he still made it. Well, there's no "ironically," but I think that's it. There's something to that.

Billy Joel's Biggest Songs: 15 Tracks That Best Showcase The Piano Man's Storytelling And Pop Hooks