Photo: Shervin Lainez

list

A Year In Alternative Jazz: 10 Albums To Understand The New GRAMMYs Category

"Alternative jazz" may not be a bandied-about term in the jazz world, but it's a helpful lens to view the "genre-blending, envelope-pushing hybrid" that defines a new category at the 2024 GRAMMYs. Here are 10 albums from 2023 that rise to this definition.

What, exactly, is "alternative jazz"? After that new category was announced ahead of the 2024 GRAMMYs nominations, inquiring minds wanted to know. The "alternative" descriptor is usually tied to rock, pop or dance — not typically jazz, which gets qualifiers like "out" or "avant-garde."

However, the introduction of the Best Alternative Jazz Album category does shoehorn anything into the lexicon. Rather, it commensurately clarifies and expands the boundaries of this global artform.

According to the Recording Academy, alternative jazz "may be defined as a genre-blending, envelope-pushing hybrid that mixes jazz (improvisation, interaction, harmony, rhythm, arrangements, composition, and style) with other genres… it may also include the contemporary production techniques/instrumentation associated with other genres."

And the 2024 GRAMMY nominees for Best Alternative Jazz Album live up to this dictum: Arooj Aftab, Vijay Iyer and Shahzad Ismaily's Love in Exile; Louis Cole's Quality Over Opinion; Kurt Elling, Charlie Hunter and SuperBlue's SuperBlue: The Iridescent Spree; Cory Henry's Live at the Piano; and Meshell Ndegeocello's The Omnichord Real Book.

Sure, these were the standard bearers of alternative jazz over the past year and change — as far as Recording Academy Membership is concerned. But these are only five albums; they amount to a cross section. With that in mind, read on for 10 additional albums from 2023 that fall under the umbrella of alternative jazz.

Allison Miller - Rivers in Our Veins

The supple and innovative drummer and composer Allison Miller often works in highly cerebral, conceptual spaces. After all, her last suite, Rivers in Our Veins, involves a jazz band, three dancers and video projections.

Therein, Miller chose one of the most universal themes out there: how rivers shape our lives and communities, and how we must act as their stewards. Featuring violinist Jenny Scheinman, trumpeter Jason Palmer, clarinetist Ben Goldberg, keyboardist and accordionist Carmen Staff, and upright bassist Todd Sickafoose — Rivers in Our Veins homes in on the James, Delaware, Potomac, Hudson, and Susquehanna.

And just as these eastern U.S. waterways serve all walks of life, Rivers in Our Veins defies category. And it also blurs two crucial aspects of Miller's life and career.

"I get to marry my environmentalism and my activism with music," she told District Fray. "And it's still growing!

M.E.B. - That You Not Dare To Forget

The Prince of Darkness may have slipped away 32 years ago, but he's felt eerily omnipresent in the evolution of this music ever since.

In M.E.B. or "Miles Electric Band," an ensemble of Davis alumni and disciples underscore his unyielding spirit with That You Not Dare to Forget. The lineup is staggering: bassists Ron Carter, Marcus Miller, and Stanley Clarke; saxophonist Donald Harrison, guitarist John Scofield, a host of others.

How does That You Not Dare To Forget satisfy the definition of alternative jazz? Because like Davis' abstracted masterpieces, like Bitches Brew, On the Corner and the like, the music is amoebic, resistant to pigeonholing.

Indeed, tunes like "Hail to the Real Chief" and "Bitches are Back" function as scratchy funk or psychedelic soul as much as they do the J-word, which Davis hated vociferously.

And above all, they're idiosyncratic to the bone — just as the big guy was, every second of his life and career.

Art Ensemble of Chicago - Sixth Decade - from Paris to Paris

The nuances and multiplicities of the Art Ensemble of Chicago cannot be summed up in a blurb: that's where books like Message to Our Folks and A Power Stronger Than Itself — about the AACM — come in.

But if you want an entryway into this bastion of creative improvisational music — that, unlike The Art Ensemble of Chicago and Associated Ensembles boxed set, isn't 18-plus hours long — Sixth Decade - from Paris to Paris will do in a pinch.

Recorded just a month before the pandemic struck, The Sixth Decade is a captivating looking-glass into this collective as it stands, with fearless co-founder Roscoe Mitchell flanked by younger leading lights, like Nicole Mitchell and Moor Mother.

Potent and urgent, engaging the heart as much as the cerebrum, this music sees the Art Ensemble still charting their course into the outer reaches. Here's to their next six decades.

Theo Croker - By The Way

By The Way may not be an album proper, but it's still an exemplar of alternative jazz.

The five-track EP finds outstanding trumpeter, vocalist, producer, and composer Croker revisiting tunes from across his discography, with UK singer/songwriter Ego Ella May weaving the proceedings with her supple, enveloping vocals.

Compositions like "Slowly" and "If I Could I Would" seem to hang just outside the reaches of jazz; it pulls on strings of neo soul and silky, progressive R&B.

Even the music video for "Slowly" is quietly innovative: in AI's breakthrough year, machine learning made beautifully, cosmically odd visuals for that percolating highlight.

Michael Blake - Dance of the Mystic Bliss

Even a cursory examination of Dance of the Mystic Bliss reveals it to be Pandora's box.

First off: revered tenor and soprano saxophonist Michael Blake's CV runs deep, from his lasting impression in New York's downtown scene to his legacy in John Lurie's Lounge Lizards.

And his new album is steeped in the long and storied history of jazz and strings, as well as Brazilian music and the sting of grief — Blake's mother's 2018 passing looms heavy in tunes like "Merle the Pearl."

"Sure, for me, it's all about my mom, and there will be some things that were triggered. But when you're listening to it, you're going to have a completely different experience," Blake told LondonJazz in 2023.

"That's what I love about instrumental music," he continued. "That's what's so great about how jazz can transcend to this unbelievable spiritual level." Indeed, Dance of the Mystic Bliss can be communed with, with or without context, going in familiar or cold.

And that tends to be the instrumental music that truly lasts — the kind that gives you a cornucopia of references and sensations, either way.

Dinner Party - Enigmatic Society

Dinner Party's self-titled debut EP, from 2020 — and its attendant remix that year, Dinner Party: Dessert — introduced a mightily enticing supergroup to the world: Kamasi Washington, Robert Glasper, Terrace Martin, and 9th Wonder.

While the magnitude of talent there is unquestionable, the quartet were still finding their footing; when mixing potent Black American genres in a stew, sometimes the strong flavors can cancel each other out.

Enigmatic Society, their debut album, is a relaxed and concise triumph; each man has figured out how he can act as a quadrant for the whole.

And just as guests like Herbie Hancock and Snoop Dogg elevated Dinner Party: Dessert, colleagues like Phoelix and Ant Clemons ride this wave without disturbing its flow.

Wadada Leo Smith & Orange Wave Electric - Fire Illuminations

The octogenarian tumpeter, multi-instrumentalist and composer Wadada Leo Smith is a standard-bearer of the subset of jazz we call "creative music." And by the weighty, teeming sound of Fire Illuminations, it's clear he's not through surprising us.

Therein, Smith debuts his nine-piece Orange Wave Electric ensemble, which features three guitarists (Nels Cline, Brandon Ross, Lamar Smith) and two electric bassists (Bill Laswell and Melvin Gibbs).

In characteristically sagelike fashion, Smith described Fire Illuminations as "a ceremonial space where one's hearts and conscious can embrace for a brief period of unconditioned love where the artist and their music with the active observer becomes united."

And if you zoom in from that beatific view, you get a majestic slab of psychedelic hard rock — with dancing rhythms, guitar fireworks and Smith zigzagging across the canvas like Miles.

Henry Threadgill - The Other One

Saxophonist, flutist and composer Henry Threadgill composed The Other One for the late, great Milfred Graves, the percussionist with a 360 degree vantage of the pulse of his instrument and how it related to heart, breath and hands.

If that sounds like a mouthful, this is a cerebral, sprawling and multifarious space: The Other One itself consists of one three-movement piece (titled Of Valence) and is part of a larger multimedia work.

To risk oversimplification, though, The Other One is a terrific example of where "jazz" and "classical" melt as helpful descriptors, and flow into each other like molten gold.

If you're skeptical of the limits and constraints of these hegemonic worlds, let Threadgill and his creative-music cohorts throughout history bulldoze them before your ears.

Linda May Han Oh - The Glass Hours

Jazz has an ocean of history with spoken word, but this fusion must be executed judiciously: again, these bold flavors can overwhelm each other. Except when they're in the hands of an artist as keen as Linda May Han Oh.

"I didn't want it to be an album with a lot of spoken word," the Malaysian Australian bassist and composer told LondonJazz, explaining that "Antiquity" is the only track on The Glass Hours to feature a recitation from the great vocalist Sara Serpa. "I just felt it was necessary for that particular piece, to explain a bit of the narrative more."

Elsewhere, Serpa's crystalline, wordless vocals are but one color swirling with the rest: tenor saxophonist Mark Turner, pianist Fabian Almazan, and drummer and electronicist Obed Calvaire.

Themed after "the fragility of time and life; exploring paradoxes seeded within our individual and societal values," The Glass Hours is Oh's most satisfying and well-rounded offering to date, ensconced in an iridescent atmosphere.

Charles Lloyd - Trios: Sacred Thread

You can't get too deep into jazz without bumping into the art of the trio — and the primacy of it.

At 85, saxophonist and composer Charles Lloyd is currently smoking every younger iteration of himself on the horn; his exploratory fires are undimmed. So, for his latest project, he opted not just to just release a trio album, but a trio of trios.

Trios: Chapel features guitarist Bill Frisell and bassist Thomas Morgan; Trios: Ocean is augmented by guitarist Anthony Wilson and pianist Gerald Clayton; the final, Trios: Sacred Thread, contains guitarists Julian Lage and percussionist Zakir Hussain.

These are wildly different contexts for Lloyd, but they all meet at a meditative nexus. Drink it in as the curtains close on 2023, as you consider where all these virtuosic, forward-thinking musicians will venture to next — "alternative" or not.

Photo: Gai Terrell/Redferns

feature

Revisiting John Coltrane's 'A Love Supreme' At 60: How The Record Ushered In A Spiritual Revival

Recorded in December 1964 and released the following January, 'A Love Supreme' not only built on the GRAMMY-winning musician's mythology but encouraged his contemporaries to seek higher ground.

Sixty years ago this month, John Coltrane and his quartet settled into Van Gelder Studio in New Jersey. Alongside McCoy Tyner on piano, Jimmy Garrison on bass, Elvin Jones on drums, and Coltrane as bandleader and on saxophone, the group recorded one of the most influential musical proclamations of all time: A Love Supreme.

The catalyst for the composition was, per Coltrane's liner notes, a "spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life" that occurred seven years prior. He continues in the liner notes, "At that time, in gratitude, I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music."

It more than certainly delivered on that wish.

Coltrane was not yet 40 years old when A Love Supreme was recorded, though he already had more than a dozen albums in his discography. Released in January 1965, A Love Supreme's influence permeated through the jazz world and culture at large — it opened doors for spiritual jazz and musical experimentation in 1965 and beyond.

The album sold a half-million copies by 1970 and earned him his first nominations for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance - Small Group Or Soloist With A Small Group and for Best Original Jazz Composition at the 8th GRAMMY Awards.

For Coltrane, the spiritual element was infused in his entire approach to musicianship and personal development. This was no concept album, it was the concept. "There's no ambiguity whatsoever about what the music is about and what Coltrane is about," says Leon Lee Dorsey, renowned jazz bassist and Berklee College of Music educator.

By the early 1960s, jazz musicians had already been evolving and experimenting since the era of bebop, with Max Roach’s We Insist! Freedom Now Suite (1960) and Ornette Coleman and Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation (1961), not to mention the futuristic sounds of Sun Ra, literally.

"[Coltrane's] transition from style to style is almost hard to process," Dorsey continues. In the late '50s, the saxophonist recorded multiple records with Miles Davis, including the legendary Round [About] Midnight and Kind of Blue, the latter of which was "already breaking the mold with modal jazz." He explains how Coltrane had gone from interpreting popular standards like "All of You" and "Bye Bye Blackbird" on Midnight, to modal jazz with the classic and influential Kind of Blue. The album was groundbreaking for its intentional break from the complexities and chord changes of bebop to modal structures. Coltrane expanded on this, later revisiting the iconic "So What" chord sequence by reimagining it for "Impressions."

"It's just a few years, but that really speaks to his spiritual and musical development," Dorsey says of Coltrane. "In my mind, what he said on Kind of Blue after his constant searching and development, he came back to that [on 1961's "Impressions"] because he was at a different level than he was [with Miles]."

Impressions as a record didn’t just reference Coltrane’s previous work and the evolving genre of jazz, but musical constructs and ideologies from all over. Compositions like "India" explore eastern musical influence and spirituality. Next, he recorded Crescent, the studio album just prior to A Love Supreme, and avante-garde jazz firmly found its way into his sound along with spiritual elements. Following that record, those elements gave way to a focused theme of spirituality, while still paying homage to pre-existing musical practices and structure.

Read more: John Coltrane, 'A Love Supreme': For The Record

Ingrid Monson, Quincy Jones Research Professor of African-American music at Harvard University, describes how the theme of A Love Supreme develops, builds, and hooks the audience, while having distinct structure and sections. "So it's almost like a little sonata form in that sense. It's got a couple of themes, that then he systematically develops that…and then he decides he's going to play the theme of A Love Supreme in all 12 keys." Then listeners hear the chant and Coltrane’s vocals, a rare inclusion that Monson describes as "This incredible moment when the voice comes in and goes down to the key [that] the next movement's going to be in."

The musical references and structure, also heavily dissected by Coltrane’s biographer, Lewis Porter, underscore both its reference and evolution of genre.

The piece was prepared in detail for a spiritual performance, as illustrated by the written manuscript for the piece. "He clearly had it planned to be in four movements and that it would feature each one of the band members [in each movement]," Monson explains. "There is an incredible ethical importance to it."

To wit, "Psalm" was also a musical narration to a prayer that Coltrane had written; its final chord is a reference to that of "Alabama," a piece Coltrane composed shortly after the Birmingham bombings, as noted in the music manuscript for A Love Supreme. "Alabama" was also inspired by the rhythm of a speech by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr; some say it was inspired by the eulogy for the four victims of the bombing. In this sense, Coltrane wasn’t using spirituality and music to reflect on existing stories, but to say something new and relevant to the times.

The complexity isn’t for the sake of being performative, it’s within the spiritual nature of the piece — something other scholars and even Tyner himself have recalled of the studio session.

Arthur Magazine described a performance not a year after the release of A Love Supreme as touching "a communal nerve." Although Coltrane only performed "Acknowledgement," "the chant from the well-known album — a year old by that point — had certainly become part of the lingua franca of the jazz circle, disseminating as well into the larger Black community."

Although spiritual jazz was an existing and evolving genre , exploration accelerated once A Love Supreme hit the world. A concentration of interest took hold through the 1960s, exemplified by Duke Ellington’s Sacred Concerts (1965-1973) and pianist/arranger Mary Lou Williams’ shift to sacred music. The Beatles would later weave spirituality into their music.

"His impact is great, equally as great as Miles, outside of jazz," Dorsey elaborates. "You see this kind of spiritual journey that musicians kind of weave into their compositions and concepts of the albums and all. He's really probably the first artist where that quest was in the titles of the songs, and his legendary musicianship was wrapped into his spiritual journey."

Coltrane's spiritual quest was unusually openly displayed compared to his contemporaries. For Coltrane, it wasn't just in the music, but in his entire approach to musicianship and personal development.

"I really do think that part of his cultural impact is that he represented this incredibly moral force that people wanted to identify with and different groups of people articulated that in different ways," says Monson. She notes how Muhammad Speaks of the Nation of Islam was initially skeptical of Coltrane’s work, later changing their view and presenting a "simple eulogy to this Black Colossus and his widow and the four small children he left behind", declaring that "his phenomenal performances opened special spheres for untold millions in this world and in the worlds to come. (Muhammad Speaks 1967: 21).

A Love Supreme changed the tides and moved so many individuals, spiritually, politically, and musically.

"I think a lot of players wouldn't have happened without him. People like Pharaoh Sanders, for example, Leon Thomas, and all that spectacular stuff they did exploring a kind of spiritual dimension," Monson notes, citing modern musicians like Kamasi Washington as continuing to move forward the needle Coltrane pushed. It’s worth noting that Pharaoh Sanders became a member of Coltrane’s band in 1965, performing on Ascension and Meditation, which firmly placed Coltrane on the map of avant garde jazz as the genre evolved.

Read more: Virtuosos, Voyagers & Visionaries: 5 Artists Pushing Jazz Into The Future

Dorsey contemplates the lasting impact of Coltrane’s music and struggles to find words to do it justice. "Like, how would you describe your mother's love?" he questions with a laugh. After all, his output was contained in just a 12 year window.

"That's almost mythological," he adds, elaborating on how Coltrane played with other jazz greats and persevered with a vision, catapulting spiritual jazz to influence generations to come. "I don't think there's a more revered jazz musician when you add that spiritual factor in."

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Khatia Buniatishvili Plays "Mephisto-Waltz No.1"

Peanut Butter Wolf Talks New Campus Christy Album & What's Next For Stones Throw

Warner Music Group's Paul Robinson To Be Honored With 2025 Entertainment Law Initiative Service Award

Your Vote, Your Voice: 6 Reasons Why Your GRAMMY Vote Matters

JOHNNYSWIM Reveal The Mic That Defines Their Sound

Photo: Per Ole Hagen/Redferns/ Getty Images

news

André 3000 On 'New Blue Sun,' Finding Inspiration In Visual Art & His New Musical Journey

The rapper-turned-flutist discusses his latest tour, how his artistic approach has evolved, and the surprising connections between his past and present music.

André 3000 is taking his show on the road, again.

The rapper-turned-flutist is beginning another tour this week in support of his debut solo recording, last year’s New Blue Sun. The two-month North American jaunt will feature André and his band — Carlos Niño, Nate Mercereau, Surya Botofasina, and Deantoni Parks — performing the kind of collective group improvisation that was featured on their spacey, atmospheric album.

It’s been nearly a year since the album’s surprise release, so the world has had time to get adjusted to André Benjamin, experimental jazz musician instead of André Benjamin, one-half of arguably the greatest rap duo of all time. And André, likewise, has had some time to get used to being back in the public eye after years of trying to escape from it — a situation he compares to diet soda in our wide-ranging conversation.

GRAMMY.com called up André to discuss the tour, but things went in many different directions. We talked about his new musical life in detail — including why he jokingly refers to himself as the Lil B of out-there jazz. And we also delved into his old one. Does he ever write raps, even if only for himself? What is it like to have millions of people who only know you as the 23-year-old young man you were when OutKast's Aquemini created a whole new lane in hip-hop, as opposed to the 49-year-old man you are, who’s more into sharing stages with alums of Yusef Lateef’s jazz bands than with Big Boi or Killer Mike?

We got into all that, and a lot more. Check it out below.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You're going out now for a new leg of shows in support of New Blue Sun. This tour is different. The venues are arts centers, concert halls, even an opera house or two. Last time it was jazz clubs and the occasional church. How are the audiences different in these sorts of venues, and how are you different as a musician and as a performer?

The venues, I think they're just getting larger because now people are finding out about it, and we've been blessed to keep getting booked in a great way. The only way the venue changes things is the sound. It may inform what we're doing.

Like, recently we did these caves in Napa Valley, and that was more intimate. It was caves, so you used the environment and the wall reverberation. That helps make decisions on what you're doing. But we've also gotten to a place now where, like you're saying, you’re performing in a larger church, and that church may have a longer [reverberation]. You do less in bigger spaces, because you're waiting for the sound to come back to you and fill it. Also, we've grown to bigger festivals, so we’re playing out in fields. And that’s even a different experience, because at that point you're playing out. We do more, you get louder.

It just depends, because it doesn’t change the original intent and formula of what we’re doing, which is listening to ourselves and responding. So the venue is just another effect or another instrument, in a way, that we have to pay attention to. It gives us guidelines of what we want to do in the space.

What role do you play in the dynamics of the band? Are you the one saying, time for a new section or an ending? Who's handling the cues?

No, [laughs] we don't have cues. As a whole, we feel it. We feel when it's resolving, or we feel when it's building. Sometimes it gets really silent, and then someone may start. We don't have a, “Hey, you go do this.” It's not that at all. It is a total collective of feeling what's happening at the time.

I may start a riff or a melody, or Nate may start like something, or Carlos may start something, or Surya may start something. And we just listen and chime in. But there are no cues like, okay, we're going to do this.

The only cue we may have is when we get together in our huddle before we go out, to ourselves, as a collective. We may say, “Let's start full on,” and whatever that means, we just dive completely in. Or we’ll say, “Let's just start in silence,” and we may sit there for 30 seconds to a minute completely silent, just listening to the crowd shuffle around. But that's our only cue a lot of times, and that's usually venue by venue or what we're feeling from the crowd. Other than that, once we start the ride, we're on our own G.P.S..

To the extent you can put it into words, what's going through your head when you play? I know you're not a trained musician who thinks in terms of notes and chords.

Sometimes, not musically at all. Sometimes it's concepts. I may be thinking pattern-ly or lines. Like if I just came from a museum or something, and I saw an artist and they used these kind of lines, [I’d think], how can I play like that? What does that sound like? And I'll try to mimic it.

Sometimes it’s just feelings. I may be agitated and try to play what that is. Because I'm not a trained musician, I have to find other ways to get to it, so I'm trying to use it as a way to describe what I'm feeling or what I'm trying to say.

As long as I have an intent, I think that's most important. I have a goal. Sometimes I'm trying to agitate people around me, or trying to play like a bird. More concept playing, and I try to translate that.

One thing that your old music and your new music has in common is rhythm and phrasing. What connections do you see between how you would rhythmically phrase things as a rapper, and how you phrase things on the flute?

That's good you say that, because I think my strongest point, because I'm not a trained musician — I don't know keys or certain harmonies, I'm all using my ear — but I can translate rhythm from what I've done before. I can translate rapping.

It’s almost as if a rapper became a guitarist, you’d probably be a better rhythm guitarist than anything, because he's played with rhythm. So yeah, a lot of things are rhythmically for me. I respond to that, because I've been in that space, and my mouth is doing that. It's rhythm.

When you were rapping, you had other groups in your Dungeon Family collective and people you probably considered your peers. Who do you consider your peers now when it comes to the type of music you and the group are making?

A long line of historical bands like Sun Ra, the Chicago Art Ensemble. Even rapper Lil B. I was joking to myself: I was like, I'm almost the Lil B of this type of music. Lil B is, they call it based rap. My son actually turned me on to Lil B.

I'm informed by all kinds of things. I'm informed by Coltrane in ways. Eric Dolphy, for sure. Pharoah Sanders, Yusef Lateef. These are all people that for years I considered gods, not even knowing that I would be going in this direction, but I responded to these people. So I think when I play, I may reference them and not even know it, because it's in me.

Sometimes we have OG players sit in with us that may have played with Yusef. We invite them on stage and after we play a set, some of the feedback that I've gotten has been really interesting about what I'm referencing and what I'm doing and who I sound like. And I'm like, wow, I'm not even trying to do a thing. But sometimes, it’s in your skin what you listen to or your sense of melody because you’ve listened to a certain thing for so long.

I'm curious to go back to the Lil B thing. What sort of parallels do you see between his approach and what you're doing?

Because a lot of what he's doing is made up or improv or really reactionary. It's not this studied, perfect thing. Because I came up in the ‘90s, we came up with Nas and Wu-Tang and some of the [people] considered the best rappers around. It was about clarity. It was more of a studied kind of thing.

A person like Lil B is not studied at all. But the way the kids respond to him, it's because of that. It's kind of like a punk way of rapping, and I like it. [And what I’m doing is] almost like punk jazz or punk spiritual jazz. It's pure feeling.

For me, it's really physical, because I'm coming from a different way. It's always been like that for me when it comes to instruments. Like, if I pick up a guitar, it's shapes in my hand, or if I'm on a piano, it's shapes on my fingers.

So when I'm playing a wind instrument, I'm physically trying to will something to happen. Some of my favorite players are physical. Kurt Cobain was physical — he wasn't the most perfect player. [Jimi] Hendrix wasn't even the most perfect player, but sometimes it was physical, what he was doing. Or Thelonius Monk, he hit the piano like it was drums. It's this physical thing that I like,

Did you connect more to Hendrix’s physicality during the time you literally had to become him for a couple of months [during the filming of the 2013 biopic Jimi: All Is by My Side]?

No. That was such an odd thing I had to do because I had to pretend to be left handed, which was very odd for me. No, it was a true acting situation.

The past year or so, what has it been like being a public person again? Are you treating it any differently than your first go-round?

It’s almost like [laughs] superstar lite, like Coke Lite or Coke Zero. It’s like Superstar Zero. You’ve got the fame, but it's not as intense as it was before. It's different. A lot of people are weirded out about the direction, so it's not the same intensity of the whole world on board with you — which is kind of cool for my age and tastes. I like this pace a lot, compared to just being all over everywhere all the time.

Then there's this other thing, too. The album has been out a year, and we recently dropped this film that we did to the album that came out a year ago, but we just released it on YouTube. So a lot of people are just now discovering the album. It's like, “Yeah, we heard something about this flute thing,” but they never heard it. Now that this video is out, a lot of people are hearing it again, or for the first time. So it's a cool thing that you kind of get this second wave of people that are just now hearing it.

Some of the ways you talk about playing remind me that your initial artistic plans, before rap, were in visual art. What connection do you see between the type of music you're doing now and the visual art you were doing when you were a teenager?

I don't necessarily see a connection from what I was doing when I was younger, visually. But as I've gotten older, now I do my own personal art study. I've never been to art school or anything, but now on YouTube, I have my own personal art history classes, and I'm learning: “Whoa, okay, Basquiat, he liked Cy Twombly. Cy Twombly, he just made these gestures on the canvas. Oh, I see Basquiat makes these gestures on the canvas.” Now I totally can see or even get influenced from a visual or physical thing, because a lot of those gestures were physical things.

It wasn't like I'm trying to make the most perfect figurative image. I'm trying to relate something. A lot of that, I can take from or be inspired by when I'm playing. Sometimes it's the only thing I have, because I don't know a certain progression or a certain series of notes. I know I'm physically doing a thing, and if I know that's matching what my ears are hearing in that key, I feel like I'm in the right place.

One thing I'm always interested in is how rappers think about rap. I've talked to artists who are like, “If I was walking down the street and saw a stop sign, I would come up with 100 rhymes for ‘stop sign,’ and it got so intrusive that I had to consciously cut that off.”

These days, do you still think of raps, even if it's only fragments or lines? If so, do you ever write them down or save them? Where are you these days in terms of composing raps or having raps come to mind?

Yeah, I totally rap all the time. I think it's just in me. But it's not an obsessive thing where if I see a brick, I have to rhyme “brick” with something. It's more of: there's a thought that's important to me. Then if there's a next line that rhymes, I go there and I'll write it down. But I'm not obsessive, where I'm trying to find every word that rhymes with “brick.” It's not an exercise for me. It's just a means to an end.

It's funny because my engineer that I'm working with now, he raps, too, and he's a younger kid. He's asking me about how I do it. He was telling me his technique — he'll find all these words that rhyme with this word. And I was like, oh, that's cool. But when I do it, it's supporting the thought more than the rhyme. The rhyme is supporting the thought. It's not seeing how many things I can rhyme. But if I have a thought and I have a next thought, I am going to try to find that.

So it's more important to support what I'm trying to say, more than rhyming. There are rappers to me that are true rhymers. The biggest way I can explain it is, some painters are just painters — that's their form, is oil on canvas. And then some artists are concept artists, some artists are emotive. It's more about the emotion or saying something. For me, it's more about what I'm saying than how I'm saying it.

What’s next for you, recording-wise?

There's always new music to come.

Anything specifically you can say about that?

No. It's too early for me to even be able to describe what’s coming. But I'm always recording and trying to figure out new ways to do stuff.

I assume you hear OutKast’s music sometimes when you’re out and about. But do you ever intentionally listen to it?

Rarely. But recently, a friend of mine sent me a video of an interview that I was doing, and I was talking about a certain song that I hadn't heard in a long time. So I went back to listen to that song, and that sent me down the rabbit hole of all my guest verses and OutKast stuff. So one day I was in my hotel room listening to all this stuff for hours — five hours of albums and guest stuff. And it was surprising because you’re listening as a fan and not remembering where you were at the time when you did them. It's almost like you're having an out-of-body experience listening to yourself. Then you realize how much time has gone by and how different of a person you are, which is even crazier.

I can imagine! The first time I saw you perform was in 2001, which was four records into your career. But that’s almost 25 years ago.

Yeah. Twenty-five years is a long, long, long, long time. So you gotta imagine listening to yourself. It’s almost like looking back at high school pictures: how your hairstyle was, how your clothes were. It's all a trip because you're like, whoa, that was a completely different time.

And what's even crazier is that the audience a lot of times, they don't grow, or they only know what you've given them. So a lot of times in their mind they're still there, and it's kind of weird. Stuff that they're hoping for from you, you've already moved past that.

A lot of people don't understand — even when you put an album out, you're past it already. You may be onto something else. But they start right then, and they only know of that. They don't know the years in between. They don't know the growth in between. And they really don't care, which is understandable. As the audience, we only know what we get — we don't know the in-betweens. It's almost like seeing your nephew that you hadn't seen for years. You only remember him as your little nephew. Then he's taller than you the next time you see him.

It's like that, but on such a grand scale, I can't imagine what it must be like for you to have millions of people whose mental image of you is when you're 23 or 25.

Yeah. And it's funny because we're almost on two different wavelengths. Even when New Blue Sun dropped, one of the biggest stories, which I didn't understand at first — but then I had to understand — was writers saying, “We wait fucking seventeen years, and he puts this out?”

To them, they're waiting. But I never said that I was about to put out an album. So in my mind, I'm not trying to be what I was 17 years ago. To me, it's just, life has gone on. It’s almost crazy to think that someone would put something out 17 years later. At ten years, I'm like, “Oh, that's done.” Even for me, I thought I was done. I really thought I was done at a certain point. And here comes a different thing. So that was surprising to me. At first, I was like, why would y’all wait 17 years for anything? And then I'm like, oh, well, that's all they know. I wasn't waiting.

Over the last couple of years leading up to the album, there was this [clip] that became famous, of you walking around and playing the flute in public. Is that something you're still doing? Are you still practicing in public?

I do it still, but it's sad in a way, because now that I've put the album out, when I do it, people expect as if I'm performing in public. But it started as a thing for me. I like to walk. I like to hike. I like to walk, and carry my flute while I do. It was just a thing.

And so when people started sneaking videos and posting them, it was not a plan or anything. I actually love to play in nature. I love to play when I'm walking, when I find caves or when I find tunnels where the reverb is awesome. I love walking and finding places to play, but now it's almost like I have to sneak off and do it. I have to be away from the public in a way to do it, so it doesn't become a thing. So I don't do it as much as I used to.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Khatia Buniatishvili Plays "Mephisto-Waltz No.1"

Peanut Butter Wolf Talks New Campus Christy Album & What's Next For Stones Throw

Warner Music Group's Paul Robinson To Be Honored With 2025 Entertainment Law Initiative Service Award

Your Vote, Your Voice: 6 Reasons Why Your GRAMMY Vote Matters

JOHNNYSWIM Reveal The Mic That Defines Their Sound

Graphic Courtesy of CBS

news

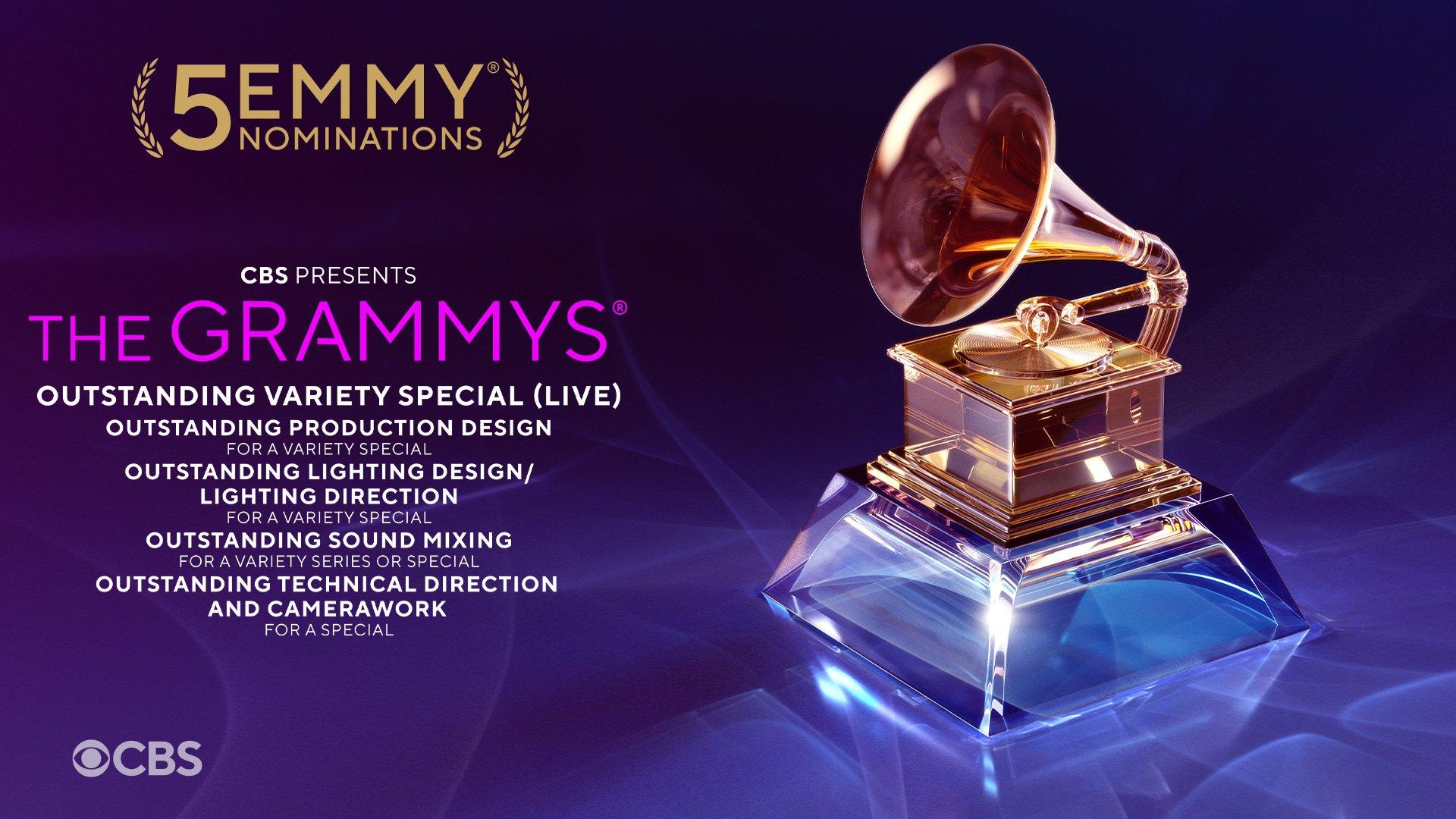

The 2024 GRAMMYs Have Been Nominated For 5 Emmys: See Which Categories

The 2024 GRAMMYs telecast is nominated for Outstanding Variety Special (Live), Outstanding Production Design For A Variety Special, and three more awards at the 2024 Emmys, which take place Sunday, Sept. 15.

It’s officially awards season! Today, the nominees for the 2024 Emmys dropped — and, happily, the 2024 GRAMMYs telecast received a whopping five nominations.

At the 2024 Emmys, the 2024 GRAMMYs telecast is currently nominated for Outstanding Variety Special (Live), Outstanding Production Design for a Variety Special, Outstanding Lighting Design/Lighting Direction for a Variety Special, Outstanding Sound Mixing for a Variety Series or Special, and Outstanding Technical Direction and Camerawork for a Special.

Across these categories, this puts Music’s Biggest Night in a friendly head-to-head with other prestigious awards shows and live variety specials, including the Super Bowl LVIII Halftime Show starring Usher as well as fellow awards shows the Oscars and the Tonys.

2024 was a banner year for the GRAMMYs. Music heroes returned to the spotlight; across Categories, so many new stars were minted. New GRAMMY Categories received their inaugural winners: Best African Music Performance, Best Alternative Jazz Album and Best Pop Dance Recording. Culture-shaking performances and acceptance speeches went down. Those we lost received a loving farewell via the In Memoriam segment.

The 2025 GRAMMYs will take place Sunday, Feb. 2, live at Crypto.com Arena in Los Angeles and will broadcast live on the CBS Television Network and stream live and on demand on Paramount+. Nominations for the 2025 GRAMMYs will be announced Friday, Nov. 8, 2024.

For more information about the 2025 GRAMMY Awards season, learn more about the annual GRAMMY Awards process, read our FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions) section, view the official GRAMMY Awards Rules and Guidelines, and visit the GRAMMY Award Update Center for a list of real-time changes to the GRAMMY Awards process.

2025 GRAMMYs: Meet The Nominees

2025 GRAMMYs: See The OFFICIAL Full Nominations List

Watch The 2025 GRAMMY Nominations Announcement Now

2025 GRAMMYs Nominations: Album Of The Year Nominees

2025 GRAMMYs Nominations: Song Of The Year Nominees

2025 GRAMMYs Nominations: Best New Artist Nominees

2025 GRAMMYs Nominations: Record Of The Year Nominees

2025 GRAMMYs Nominations: Producer Of The Year Nominees

2025 GRAMMYs Nominations: Songwriter Of The Year Nominees

2025 GRAMMY Nominations: See Shaboozey, Anitta, Teddy Swims & More Artists' Reactions

Beyoncé & Taylor Swift Break More GRAMMY Records, Legacy Acts Celebrate Nods & Lots Of Firsts From The 2025 GRAMMY Nominations

2025 GRAMMYs Nominations: Best African Music Performance Nominees

Who Are The Top GRAMMY Awards Winners Of All Time? Who Has The Most GRAMMYs?

How Much Is A GRAMMY Worth? 7 Facts To Know About The GRAMMY Award Trophy

The Impact Of A GRAMMY Win: Life After The Award

2025 GRAMMYs To Take Place Sunday, Feb. 2, Live In Los Angeles; GRAMMY Awards Nominations To Be Announced Friday, Nov. 8, 2024

GRAMMY Awards Updates For The 2025 GRAMMYs: Here's Everything You Need To Know About GRAMMY Awards Categories Changes & Eligibility Guidelines

Recording Academy Renames Best Song For Social Change Award In Honor Of Harry Belafonte

The Recording Academy Adds More Than 3,000 Women GRAMMY Voters Since 2019, Surpassing Its 2025 Membership Goal

Photo: Paul Natkin/Getty Images

list

8 Ways Sade's 'Diamond Life' Album Redefined '80s Music & Influenced Culture

As Sade's masterpiece 'Diamond Life' turns 40, see how the group's debut pushed R&B forward and introduced them as beloved elusive stars.

"I only make records when I feel I have something to say," Sade Adu asserted in 2010 upon the highly anticipated release of Sade's GRAMMY-winning Soldier of Love album, which arrived after a 10-year hiatus. "I'm not interested in releasing music just for the sake of selling something. Sade is not a brand."

This lifetime of dedication toward achieving musical excellence helped Sade — vocalist Adu, bassist Paul S. Denman, keyboardist Andrew Hale, and guitarist/saxophonist Stuart Matthewman — gain prominence in the mid-80s, also garnering enormous respect from fans, critics, and peers alike. Formed in 1982, the English band is one of the few acts that can still be met with a hungry audience after disappearing from the spotlight for multiple years.

In an industry where churning out a new body of work is expected every couple of years, the four meticulous members of Sade move on their own time, putting out a mere six studio albums since 1984. Every project becomes more exquisite than the last, but it all began 40 years ago with Sade's illustrious debut album, Diamond Life. Ubiquitous hits like "Smooth Operator" and "Your Love Is King" appealed to listeners young and old — offering a unique blend of R&B, jazz, soul, funk, and pop that birthed a new sound and forced the industry to take notes from the jump.

As Sade's Diamond Life celebrates a milestone anniversary, here's a look at how the album helped push R&B forward, and why it's just as relevant today.

It Helped Set Off The "Quiet Storm" Craze

By mid-1984, Michael Jackson, was riding high off of winning the most GRAMMYs in a single night (including Album Of The Year) for his blockbuster album Thriller, Madonna celebrated her first top 10 hit with "Borderline," and Prince's Purple Rain was just days away from its theatrical release. Duran Duran, Culture Club, Billy Idol, and the Police were mainstays, while "blue-eyed soul" in particular had also hit an all-time high thanks to Hall and Oates, Wham, Simply Red, and others. What's more, many Black artists like Lionel Richie and Whitney Houston opted for more of a pop sound to appeal to broader audiences during MTV's golden era.

Diamond Life was refreshing at the time, as it fully embraced soul and R&B. The album offered a chic sophistication amid the synth-heavy pop and rock music that ruled the charts.

Singles like "Your Love Is King" and "Smooth Operator" introduced jazz elements into mainstream radio. In turn, Sade helped usher in the "quiet storm" genre — R&B music at its core, with strong undertones of jazz for an ultra-smooth sound. Sade and Diamond Life also laid some of the groundwork for neo-soul, which saw a surge in the '90s à la Lauryn Hill, Maxwell, and Erykah Badu.

It Made GRAMMY History

In the 65-year history of the GRAMMYs, a small number of Nigerian artists, including Burna Boy and Tems, have won a golden gramophone. In 1986, a then 27-year-old Sade Adu made history as the first-ever Nigerian-born artist to win a GRAMMY when she and her band was crowned Best New Artist at the 29th GRAMMYs. Still, Billy Crystal and Whoopi Goldberg had to accept the award on Sade's behalf — signaling Adu's elusive nature as she rarely attends industry events or grants interviews.

Since then, Sade has gone on to earn three more GRAMMYs, including Best Pop Vocal Album in 2001 for their fifth studio album, Lovers Rock. The win signified their staying power in the new millennium.

It Birthed The Band's Signature Song…

While Diamond Life spawned timeless hits like "Your Love Is King" and "Hang On to Your Love," "Smooth Operator" became the album's highest-charting single — and remains the most iconic song in their catalog. The seductive track about a cunning two-timer propelled the band into international stardom: "Smooth Operator" skyrocketed to No. 5 on the Billboard Hot 100 and hit No. 1 on the Adult Contemporary chart.

Even non-Sade fans can identify "Smooth Operator" in an instant, from Adu's unmistakable vocals to that now-iconic instrumental saxophone solo. As of press time, it boasts over 400 million Spotify streams alone, and has remained a set list staple across every one of Sade's tours.

…And It Houses Underrated Gems

"Smooth Operator" may be Sade's commercial classic, but deep cuts like "Frankie's First Affair," "Cherry Pie," and "I Will Be Your Friend" are fan favorites that embody the band's heart and soul.

"Frankie's First Affair" offers a surprisingly enchanting take on infidelity: "Frankie, didn't I tell you, you've got the world in the palm of your hand/ Frankie, didn't I tell you they're running at your command." And, it's impossible to resist the funky groove that carries standout track "Cherry Pie," which served as a catalyst for some of Sade's later, more dance-oriented hits, including "Never As Good As the First Time" and "Paradise." Some of Sade's most poignant statements about lost love, including "Somebody Already Broke My Heart" from 2000's Lovers Rock, can be traced back to "Cherry Pie."

Diamond Life's penultimate song, "I Will Be Your Friend," offers both solace and companionship — another recurring theme throughout Sade's music, from 1988's "Keep Looking" to 2010's "In Another Time."

It Was The Best-Selling Debut Album By A British Female Singer For More Than Two Decades

Sade has sold tens of millions of albums worldwide, but Diamond Life remains the band's most commercially successful LP with over 7 million copies sold. Most of Sade's other platinum-selling LPs, including Diamond Life's follow-up, 1985's Promise, boast sales between four and six million copies.

The 7 million feat helped Sade set the record for best-selling debut album by a British female singer. She held the title for nearly 25 years until Leona Lewis' 2008 album Spirit, which has sold over 8 million copies globally.

It Introduced Sade Adu As A Style Icon

When we first met Adu, her signature aesthetic consisted of a long, slicked-back ponytail, red lip, and gold hoops. Sade's impeccable style is front and center in early videos like "When Am I Going to Make a Living," in which she sports an all-white ensemble paired with a pale gray, ankle-length trench coat and loafers.

Adu rocked the model off-duty style long before it became a trend. Her oversized blazers, classic trousers, and head-to-toe denim looks were as effortless as they were chic and runway-ready — proving that less was more amid the decade of excess.

"It's now so acceptable to be wacky and have hair that goes in 101 directions and has several colours, and trendy, wacky clothes have become so acceptable that they're… conventional," Adu, who briefly worked as a fashion designer and model before pursuing music, told Rolling Stone in 1985. "I don't like looking outrageous. I don't want to look like everybody else."

It Shined A Light On Larger Societal Issues

While most of Diamond Life leans into love's ebbs and flows, a handful of tunes deal with financial strife coupled with a dose of optimism, as evidenced by "When Am I Going to Make a Living" and "Sally." The latter song characterizes the Salvation Army as a young charitable woman: "So put your hands together for Sally/ She's the one who cared for him/ Put your hands together for Sally/ She was there when his luck was running thin."

Meanwhile, Adu, a then-starving artist, scribbled down portions of "When Am I Going to Make a Living" on the back of her cleaning ticket. The soul-stirring "We are hungry, but we won't give in" refrain emerges as a powerful mantra in the face of adversity and still holds relevance in 2024. Similar themes appear throughout Sade's later work, including unemployment ("Feel No Pain"), unwanted pregnancy ("Tar Baby"), survival ("Jezebel"), prejudice ("Immigrant"), and injustice ("Slave Song").

Diamond Life closer "Why Can't We Live Together" is a well-done cover of Timmy Thomas' 1972 hit about the staggering Vietnam War deaths. The band wisely doesn't veer too far from the original recording, but Adu's distinctive contralto voice brings a haunting quality that's reminiscent of Billie Holiday.

It Ignited The Public's Ongoing Fascination With Sade Adu

Since 1984, Sade has only released six studio albums, and a remarkable 14 years have passed since the group's last offering, 2010's Soldier of Love. Ironically, that scarcity — both in terms of music and access to the artist — has actually added to Adu's appeal. Case in point: Sade's sold-out Soldier of Love Tour grossed over $50 million in 2011, and the band still brings in close to 14 million monthly listeners on Spotify.

Adu's striking beauty, mysterious persona, and knack for letting her music do all the talking has earned the admiration of her peers across genres and generations. Everyone from Beyoncé to Kanye West to Snoop Dogg have sung her praises. Drake even has two portrait-style tattoos of the singer on his torso. Prince reportedly described 1988's "Love Is Stronger Than Pride" as "one of the most beautiful songs ever." Metalheads Chino Moreno of the Deftones and Greg Puciato of the Dillinger Escape Plan have also cited Adu as inspiration — showing that her influence runs far and wide.

In 2022, reports circulated that Sade was recording new music at Miraval Studios in France. But upon Diamond Life's 40th anniversary, "Flower of the Universe" and "The Big Unknown" from the respective soundtracks to 2018 films A Wrinkle in Time and Widows stand as Sade's latest releases.

Whether fans get new music anytime soon remains to be seen, but the impressive repertoire of Adu, Denman, Hale, and Matthewman is one that aims to be truth-seeking and inspiring while exploring life's peaks and valleys. Diamond Life in particular holds up as one of the purest representations of the group's creative legacy, both commercially and musically.

From quadruple platinum status to resonating with several generations, Diamond Life will forever stand as a remarkable debut — one that continues to influence music in a multitude of ways.

Latest News & Exclusive Videos

Khatia Buniatishvili Plays "Mephisto-Waltz No.1"

Peanut Butter Wolf Talks New Campus Christy Album & What's Next For Stones Throw

Warner Music Group's Paul Robinson To Be Honored With 2025 Entertainment Law Initiative Service Award

Your Vote, Your Voice: 6 Reasons Why Your GRAMMY Vote Matters

JOHNNYSWIM Reveal The Mic That Defines Their Sound